Writing on Desire and Dehumanization

With great pride, not the synthetic kind

Writing for Women Are Human

Everything is against the likelihood that it will come from the writer’s mind whole and entire. Generally material circumstances are against it. Dogs will bark; people will interrupt; money must be made; health will break down. Further, accentuating all these difficulties and making them harder to bear is the world’s notorious indifference. It does not ask people to write poems and novels and histories; it does not need them. It does not care whether Flaubert finds the right word or whether Carlyle scrupulously verifies this or that fact. Naturally, it will not pay for what it does not want.

- Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own1

I am reposting the first book review I wrote for Women Are Human in June 2020 to make it more easily accessible, as Women Are Human has been on hiatus since November 2022. The website remains available, with many issues accessing it due to popups and technical errors that may never be addressed. During its time, Women Are Human covered news stories related to transgenderism, particularly male violence against women and the misidentification of male criminals as “female.” When I volunteered, I contributed book reviews, long-form essays, and dialogue pieces. I find it necessary to archive this work, if only to prevent it from being lost, but I first want to remember Women Are Human.

Engaged in these issues since 2017, Diana Shaw, the founder of Women Are Human (2018-2022), whose real name has remained unknown even to me, left this activism following an incident of a man stalking her in real life. Increasingly, with good reason, Shaw came to see the activism—and the often-thankless labor behind it—as lacking material support, being wholly unsustainable, even a drain on her vitality. Writers already receive virtually no support for our work—and writers critical of transgenderism are even worse off in opposition to an industry that further toxifies professional life.

When not independently wealthy, those rarest of cases, most of us rely on various jobs—teaching and tutoring, as examples—and working alongside our families who keep us dangling just above the jaws of poverty. In fact, I find time writing apart from helping my parents at their laundromat, which is a joy in talking with people every day—sometimes, rarely, about the very issues discussed here. Therefore, despite many words of love, but lacking much financial contribution from readers of Women Are Human, it makes sense that Shaw left this activism.

I have chosen a few selections from the “About Us” page for Women Are Human to give a sense of the work done and why it mattered—and continues to matter:

Women are not a concept in a man’s brain, a feeling a man has, a costume a man puts on, a type of performance, a state of nirvana a man can achieve through drugs, a dysphoria that haunts a man’s mind, or a disease to be treated with pharmaceutical medicine or surgery . . . Women Are Human, which was created in March 2018 and fully launched by June 2018, is dedicated to exploring the totalitarian impact of the gender identity movement on society as a whole, and particularly on women and girls, in every aspect of life, from identity, legal rights, health care, privacy, safety, sexuality, participation in sports, careers and politics, and more . . . Our goal is to educate and spur our readers to take social, political, and economic action, and to provide the information and resources with which to do so.2

Women have discovered, as Woolf recognized, “not indifference but hostility.” To her analysis, we may add that writing for women, the kind that does not market prostitution and transgenderism, finds not only hostility but also poverty before praise. “The world said with a guffaw, Write? What’s the good of your writing?”3 Woolf pictures it perfectly. With great pride, not the synthetic kind, and zero illusions, I count myself among the handful of volunteers for Women Are Human, who still write—in spite of what has seemed impossible. The writer discovers the world does not pay for what it does not want, but the writer may write in rebellion against both indifference and hostility.

Desire as Dehumanization

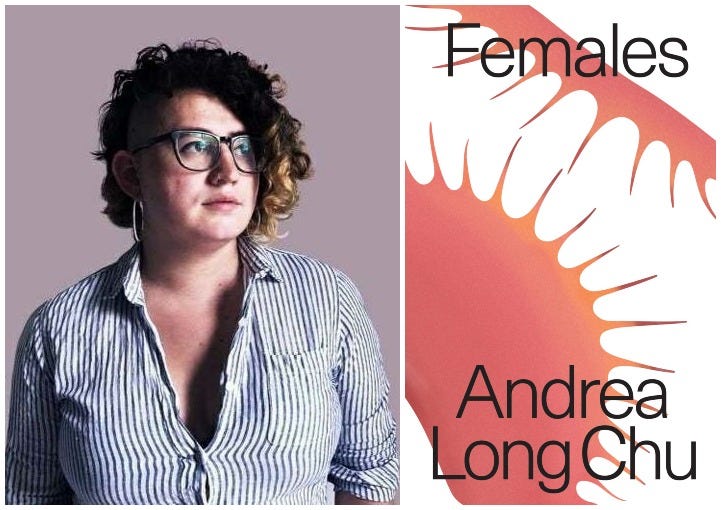

A Review of Females

Donovan Cleckley, “Desire as Dehumanization: A Review of Females,” Women Are Human, June 13, 2020, https://www.womenarehuman.com/desire-as-dehumanization-a-review-of-females.

Andrea Long Chu’s 2019 book Females—about “femaleness” and “transness”—has received generally positive reviews from so-called “left-wing” publications, being seen, almost unquestionably, and yet unsurprisingly, as both stunning and brave. Chu situates this text upon the following premise: “Everyone is female, and everyone hates it.”4 Author of the 1987 work, “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttranssexual Manifesto,” and acclaimed for founding the academic field of “transgender studies,” Sandy Stone praised Chu’s work as having launched “the second wave” of “transgender studies.”5 Stone refers, here, to Chu’s 2018 essay, “On Liking Women,” in which Chu writes: “The truth is, I have never been able to differentiate liking women from wanting to be like them.”6 As expected, Chu’s Females further develops ideas seen in that earlier essay, namely the notion, also shared by Stone, that a heterosexual male can be, in fact, a “homosexual female.”

Of autogynephilia, Chu writes that it “describes not an obscure paraphilic affliction but rather the basic structure of all human sexuality.” Autogynephilia exists at the intersection of autoeroticism, fetishism, and narcissism, a physiological and psychological condition specific to male sexual development that depends on men’s sexual objectification of women. Chu quotes the sexologist Ray Blanchard who, in 1989, wrote: “All gender dysphoric males who are not sexually oriented toward men are instead sexually oriented toward the thought or image of themselves as women.” Despite being a heterosexual male, Chu insists on being both “female” and “homosexual.” After all, if “everyone is female,” as Chu writes, all sex is “lesbian” sex, “because no other kind of sex is possible.”7

For men, their castration can become both a cause and a consequence of enhanced titillation, rather than exclusively terrifying in this controlled “loss” of power.

“Sissy porn did make me trans,” Chu tells us. “At very least it served as a neat allegory for my desire to be female—and increasingly, I thought, for all desire as such.” With the humiliation of men by women as a theme, this genre of pornography is characterized by what Chu describes as “forced feminization.”8 Julia Serano uses this phrase in the 2007 book Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity. According to Serano, “forced feminization” involves, specifically for men, “turning the humiliation you feel into pleasure, transforming the loss of male privilege into the best fuck ever.”9 For men, their castration can become both a cause and a consequence of enhanced titillation, rather than exclusively terrifying in this controlled “loss” of power.

Correspondingly, for Chu, “femaleness” becomes essentially synonymous with powerlessness, because, as Chu writes, “the phrase forced feminization is redundant: the female is always the product of force, and force is invariably feminizing.”10 Structured by the sexual objectification of the female body within the male gaze, pornography affects what has been called “gender identity development,” since sex and sexual orientation both clearly precede and differentially influence what is defined as “gender identity.”

“Pornography is what it feels like when you think you have an object, but really the object has you,” Chu writes. “It is therefore a quintessential expression of femaleness.” More precisely, rather, Chu could say, perhaps even likely would say, that the object is you, since, according to Chu, “desire is this external force,” being “nonconsensual,” since “most desires aren’t desired.”11 For the male consumer of pornography wanting to become the consumed female, what he consumes, as in the case of Chu, becomes that with which he most deeply identifies his sense of self. Pornography emerges as not only a political ideology but also a personal identity, fused together in both theory and practice.

Pornography emerges as not only a political ideology but also a personal identity, fused together in both theory and practice.

Given that, like in “On Liking Women,” Chu writes about growing up as a heterosexual male desiring to become the object of Chu’s own desire, we see in Females a definition of “transness” and “femaleness” rooted in a sense of the self as an object for someone else’s desire. “Gender transition, no matter the direction, is always a process of becoming a canvas for someone else’s fantasy,” Chu explains. Continuing, Chu tells us: “Gender is not just the misogynistic expectations a female internalizes but also the process of internalizing itself, the self’s gentle suicide in the name of someone else’s desires, someone else’s narcissism.”12

Central to Chu’s Females, alongside the misreading of Valerie Solanas from the point of view of a heterosexual male who sees himself as a “homosexual female,” we see a misreading of Catharine A. MacKinnon’s 1982 analysis of sexism. Drawing upon the work of Andrea Dworkin, MacKinnon writes:

Sexual objectification is the primary process of the subjection of women. It unites act with word, construction with expression, perception with enforcement, myth with reality. Man fucks woman; subject verb object.13

Indeed, Chu seems to take the sexual objectification of the female body, which feminists critique in the male-defined standards of femininity imposed upon women, and sees such expectations, rather, as what it is to be, in essence, “female.” “To be for women, imagined as full human beings, is always to be against females,” Chu writes. “In this sense, feminism opposes misogyny precisely inasmuch as it also expresses it. Or maybe I’m just projecting.”14 Perhaps, instead, feminism exposes misogyny—while Chu, in fact, does project.

For the male consumer of pornography wanting to become the consumed female, what he consumes, as in the case of Chu, becomes that with which he most deeply identifies his sense of self.

Projection seems to be the perfect word for describing Chu’s Females, since what Chu describes as “femaleness” is fundamentally the projection of male fantasy; it might as well be titled Fantasies. One is “female” insofar as one is “feminine,” because “femaleness” and “femininity,” to Chu, become one and the same, exactly what happens when sex and “gender identity” collapse into each other. What men have perceived as “female” has been enforced, by social institutions, as “femaleness,” gender stereotypes becoming seen as “sex traits,” uniting the process of men mythologizing women with the practice of realizing “womanhood.” And so, with Females, where the personal meets the political, male fantasy becomes female reality, yet again.

Notes on “Desire as Dehumanization”

I write that “autogynephilia,” though euphemized as the man’s “love” of himself as a woman, consists of multiple components worth clarifying—namely, autoeroticism, fetishism, and narcissism. Chu exhibits autoeroticism, though suppressed through a hatred of his male body and its sexual function, taken to the level of hormonal and surgical castration; fetishism, evident in the effects of “sissy porn” on him; and narcissism, staggeringly obvious upon reading his Females. As opposed to a greater interest directed toward the objects of desire impacted by a given paraphilia, most of which involve male-perpetrated acts of harm, there has been more of a fixation on using paraphilic language than qualifying the conditions.

There is an increasing tendency among recent proponents of “autosexuality” to read any incidence of autoeroticism in an individual’s sexual history as de facto “autosexuality,” indicative of “autogynephilia” for men and “autoandrophilia” for women. Such black-and-white categorizing, however, seems less about careful observation and far more about the obsessive fixation on the categories themselves. A shift from descriptive to prescriptive would seem especially true for people with autism failing to acknowledge their special interest as part of motivated reasoning that biases their perspective and prevents objectivity. Dichotomous thinking mediated by intolerance of uncertainty is an issue worth introspection for self-identified “autosexual” people with autism “diagnosing” others as being “autosexual.”

As I will be discussing in my critique of psychologist and sexologist John Money, paraphilic language following his tradition functions more to conceal than to reveal sexual behavior. The naming euphemizes harm and obscures the actual impacts on the objects of desire, whether in the cases of “autogynephilia” and “autoandrophilia” or “pedophilia” and its related “autopedophilia.” For instance, Money argues, “Pedophilia should just be accepted for its etymological meaning, which is simply the love of children.”15 But what does “the love of children” truly mean here? Euphemisms only work for so long before one discovers how such language can obscure reality.

See Noi Suzuki and Masahiro Hirai, “Autistic Traits Associated with Dichotomic Thinking Mediated by Intolerance of Uncertainty,” Scientific Reports 13, no. 1 (2023): Article 14049, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41164-8.

Referencing him in the Yale Journal of Law and Feminism, without any critique of the woman hating in his Females, Catharine A. MacKinnon, finds that Chu provides “evocative and intelligent accounts” (p. 91). This same man, who recently won a Pulitzer, has written, “At the center of sissy porn lies the asshole, a kind of universal vagina through which femaleness can always be accessed” (p. 76). Did MacKinnon have a stroke? No, seriously, I am concerned—and far more women should be, especially if MacKinnon trips over herself bowing to a man who argues that pornography “is therefore a quintessential expression of femaleness” (p. 63). A man arguing that pornography has “made” him into a woman, by “forced feminization,” no more opposes sexism than a white person in blackface opposes racism by making us gaze upon the racist caricature produced by racism. Here is “transgender feminist theorization,” what MacKinnon calls “brilliant” (p. 91). Who knew all Norman Mailer had to do was declare himself a woman and write essentially the same ideas expressed throughout Chu’s Females and MacKinnon would embrace Mailer’s “transgender feminist theorization”? The old misogynist did not call himself a woman; the new one does, knowing the irrational capital accorded to him that reiterates male supremacy through woman’s sexual object status.

Here is a passage from MacKinnon’s 1982 essay, which applies very well to Chu’s Females, if only she would take a moment to reconsider what she mistakes as “brilliant”:

For women, there is no distinction between objectification and alienation because women have not authored objectifications, we have been them. Women have been the nature, the matter, the acted upon, to be subdued by the acting subject seeking to embody himself in the social world. Reification is not just an illusion to the reified; it is also their reality. The alienated who can only grasp self as other is no different from the object who can only grasp self as thing. To be man’s other is to be his thing. (pp. 541-542)

See Catharine A. MacKinnon, “A Feminist Defense of Transgender Sex Equality Rights,” Yale Journal of Law and Feminism 34, no. 2 (2023): 88-96. See also Catharine A. MacKinnon, “Feminism, Marxism, Method, and the State: An Agenda for Theory,” Signs 7, no. 3 (Spring 1982): 515-544, https://doi.org/10.1086/493898.

For the sake of my sanity, I have changed the one instance of “people observed female at birth” to “women.” Thus, “the male-defined standards of femininity imposed upon people observed female at birth” becomes “the male-defined standards of femininity imposed upon women.” Also, for the sake of my sanity, I have changed the other instance of “people observed male at birth” to “men.” Thus, “‘forced feminization’ involves, specifically for people observed male at birth” becomes “‘forced feminization’ involves, specifically for men.” Terms like “female people” or “male people” and “people observed female at birth” or “people observed male at birth,” though well-intended, should be discarded in exchange for just using “women” and “men.” Years ago, perhaps, I would have agreed on some linguistic concessions, done more from submission than kindness, but now there should be none. I even limit my use of “trans-identified female” and “trans-identified male,” though reporting on cases of people, mostly men, claiming a “trans” identity merits the use to distinguish from other cases. We need to affirm that females are women and males are men, that femininity is not femaleness or womanhood any more than masculinity is maleness or manhood. The conflation of “femininity” and “masculinity,” as otherwise culturally defined concepts, with the biological states of femaleness and maleness has been part of what upholds the prevailing confusion.

If you are unable to become a paid subscriber through Substack, then please feel free to donate via PayPal, if able. I am grateful for reader support!

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 67.

Women Are Human, “About Us,” https://www.womenarehuman.com/about-us.

Woolf, 68.

Andrea Long Chu, Females (New York: Verso, 2019), 35.

Sessi Kuwabara Blanchard, “Andrea Long Chu Is the Cult Writer Changing Gender Theory,” Vice, September 11, 2018, https://www.vice.com/en/article/ev74m7/andrea-long-chu-interview-avital-ronell-gender: “Sandy Stone, the artist and academic regarded as the founder of transgender studies, lauded Chu’s break-out piece for ‘launching ‘the second wave’ of trans studies.’” Interestingly, the original link to Stone’s commendation, once featured on Chu’s website, does not seem to work anymore.

Andrea Long Chu, “On Liking Women,” n+1 30 (Winter 2018): 47, https://www.nplusonemag.com/issue-30/essays/on-liking-women.

Chu, Females, 72-74, 1. Chu describes Blanchard as “a truly loathsome man who on his own justifies the inclusion of ‘psychiatrists and clinical psychologists’ on SCUM’s hit list,” for Blanchard “considers trans women to be male”—an unforgivable heresy against fantasy (p. 72).

Chu, 79, 75.

Julia Serano, Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity, 2007 (Berkeley: Seal Press, 2016), 274.

Chu, Females, 84.

Chu, 63, 79.

Chu, 30, 35.

Catharine A. MacKinnon, “Feminism, Marxism, Method, and the State: An Agenda for Theory,” Signs 7, no. 3 (Spring 1982): 541, https://doi.org/10.1086/493898.

Chu, 14.

John Money, “Interview: John Money,” by Joseph Geraci and Donald Mader, Paidika: The Journal of Paedophilia 2, no. 3 (Spring 1991): 3.

“…the phrase forced feminization is redundant: the female is always the product of force, and force is invariably feminizing.”

This caught my attention - all of your article did, but this quote did so to a particular degree.

To clarify its significance to me, I’ll rephrase it as: “the use of male force against another person, of either sex, feminizes them;” and, contextually (and reductively, as Chu’s work is), this becomes something along the lines of “to be male is to dominate; to dominate is to meld the two essential elements of masculinity, which are power-over, and sexual violence; and the person so aggressed against and forced against their will is, by that male’s triumph, *made female,* which, to masculinity, means subject-to, overcome, and (specifically) sexually debased - which is the lesson essential to knowing what being female is.

Despite my utter contempt for Chu and for his theories, this way of defining what being feminine is, therefore what being female should and must be, while not new, resonated newly. I felt that my understanding of the male sex-and-dominance paradigm - the “why” of *why* do men, almost universally, sexually threaten and rape, why do men make and use porn, why do men harass women and feel free to demand our time and attention, why do man want harems, why do men fight, why do men make war against each other and claim their victor’s right to the conquered side’s women, girls, and (other) belongings - was made clearer. To win, to force, is in and of itself sexual to them, because it places them at the apex of masculinity - the hero-despot-(successful narcissist) that all men accept as better than they are, and all women, perforce, belong to.

I hope I’m expressing myself clearly. Feminism has been the lens through which I see and analyze the human world - in that sense, this idea isn’t at all new; Dworkin, Daly, Frye, and many other women have articulated it before.

Perhaps I found it so helpful because Chu’s premise - that force is what a man is, that forced is what a woman is, and that within trans ideology, these are the functional definitions of both - that allowed me to make a little more sense of the logic inherent in that ideology.

In any case, thank you for your shedding of light on the impenetrable toxic, woman-hating, -needing , and -fearing sludge that trans/queer theory is.