Thinking with Andrea Dworkin Thinking on Norman Mailer

Learning from the resistance to sexual liberalism

The superiority of the woman, like the superiority of the sand, is in her simplicity of means, her quiet and patient endurance, the unselfconsciousness of her touch, its ruthless simplicity. She is not abstract, not a silhouette. She lives in her body, not in his imagination.

Andrea Dworkin, Intercourse1

Nikki Craft and I first posted this introduction I wrote to the Andrea Dworkin Archival Project (ADAP) Facebook page on December 31, 2023. The original text of Dworkin’s essay, as scanned, can be read at the ADAP page. We provided a typed version of Dworkin’s 1973 critique of Mailer, as published in OUT, which we hope will be of value to readers. My desire is that readers actually read Dworkin’s work—especially Intercourse (1987)—and seek to understand the circumstances of her writing: why it is as it is. This introductory text is part of a work in progress that I am writing on women’s rights, literary history, and the disillusion of revolutions—sexual, political, and medical.

We of the ADAP especially thank Andrea Clark for purchasing the magazine and permitting us to scan it to document this largely unknown work by Dworkin and Susan Kollontai (1967-2023), whose support and friendship has been invaluable for the initial work on the ADAP. The work is rigorous, but the rigor matters. Dworkin deserves nothing less than the best, morally and intellectually, in her memory. We thank Miloš Urošević for his friendship and for sharing the text of the August 1973 version with us, for personal use, making it possible to cross reference the two versions for this analysis.

Without friends, those who care the way desperately so few do, in creativity and courage, this work would be virtually impossible.

To start, I have added three selected passages from Mailer: The Prisoner of Sex (1971), Marilyn (1973), and Genius and Lust (1976). Dworkin’s analysis begins and ends the five selections, starting with Right-wing Women (1983) and ending with “Why Norman Mailer Refuses to Be the Woman He Is” (1973). For some time, I have thought, at least partly, one reason many readers misunderstand Dworkin, if not deliberately in distortion, has been their lack of familiarity with the material being analyzed—in a word, illiteracy. Perhaps the readers know what men like Mailer say and do, but they choose to blame women like Dworkin anyway for the heresy of challenging male entitlement to women’s bodies. Readers have punished Dworkin for restating what men like Mailer have stated but insisting on dignity for women against their pervasive dehumanization in the man-made world. “In exposing the hate men have for women,” she writes, “it is as if it becomes mine.”2 With this astonishing woman-hating illiteracy pervading such a world, there should be more thinking with and on than otherwise without. This analysis follows Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans (1925) in having a main narrative with Dworkin on Mailer alongside a metanarrative about genealogy—here, the making of ideas.

Norman Mailer remarked during the sixties that the problem with the sexual revolution was that it had gotten into the hands of the wrong people. He was right. It was in the hands of men.

- Andrea Dworkin, Right-wing Women3

Where a man can become more male and a woman more female by coming together in the full rigors of the fuck—a sentimental notion to which the Prizewinner was bound to subscribe—homosexuals, it can be suggested, tend to pass their qualities over to one another, for there is no womb to mirror and return what is most forceful or attractive in each of them. So the male gets more womanly and the queer absorbs the masculinity of the other—at what peculiar price literature, not science, will be more likely to inform us. […] Yes, it is the irony of prison life that it is a world where everything is homosexual and yet nowhere is the condition of being a feminine male more despised. It is because one is used, one is a woman without the power to be female, one is fucked without a womb, that is to say without awe. For whatever else is in the act, lust, cruelty, the desire to dominate, or whole delights of desire, the result can be no more than a transaction—pleasurable, even all-encompassing, but a transaction—when no hint remains of the awe that a life in these circumstances can be conceived. Heterosexual sex with contraception is become by this logic a form of sexual currency closer to the homosexual than the heterosexual, a clearinghouse for power, a market for psychic power in which the stronger will use the weaker, and the female in the act, whether possessed of a vagina or phallus, will look to ingest or steal the masculine qualities of the dominator. It could even be said that the development of Women’s Lib may have run parallel to the promulgation of the Pill.

- Norman Mailer, The Prisoner of Sex4

Had a libido ever been concocted before out of such tender love mixed into the high voltage of such blank hate? A product issued forth from her pores. She emanated sex, a simple sweet girl on still another back street, emanated sex like few girls ever did. It was as if her adolescence had come forth out of so many broken starts and fragmented pieces of personality forcibly begun and more quickly interrupted that libido seemed to ooze through her, and ooze out of her like a dew through the cracks in a vase. Long before other adolescents could even begin to comprehend what relation might exist between this first rush of sex to their parts and the still unflexed structure of their young character, she was already without character. So she gave off a skin-glow of sex while others her age were still cramped and passionate and private; she had learned by Mind to move sex forward—sex was not unlike an advance of little infantrymen of libido sent up to the surface of her skin. She was a general of sex before she knew anything of sexual war.

- Norman Mailer, Marilyn5

It is as if every man must have in addition to everything else a sexy statue—some embodiment (here prissy) of all the non-sexuality and anti-sexuality imbibed from all the cold and disinterested women of childhood, and yet succeed somehow in converting that cold marble to flesh sweet and happy at room temperature. So he makes love to his ex-wife like a pirate opening a chest or a terrorist blowing up a factory, a sex murderer whose weapon is his phallus. It is social artifice he would slay first, and hypocrisy, and all the cancers of bourgeois suffocation. ‘Take that, you cunt,’ is his war cry. Yet the enigma of woman’s nature (if she has, that is, a nature, and is not merely a person altogether equal, hoof to human hoof, with man), the enigma, if it exists, is that women respond to him, of course they do, it is the simple knowledge of the street that murderers are even sexier than athletes. Something in a woman wishes to be killed went the old wisdom before Women’s Liberation wiped that out, something in a woman wishes to be killed, and it is obvious what does—she would like to lose the weakest part of herself, have it ploughed under, ground under, kneaded, tortured, squashed, sliced, banished, and finally immolated. Burn out my dross is the unspoken cry of his girls—in every whore is an angel burning her old rags.

- Norman Mailer, Genius and Lust6

he has created definitions which serve him, and he will impose those definitions on all manner of experience because they serve him.

- Andrea Dworkin, “Why Norman Mailer Refuses to Be the Woman He Is,” in OUT, December 19737

Liberated from the Revolution

Be careful. Of a. Detachment.

- Gertrude Stein, How to Write8

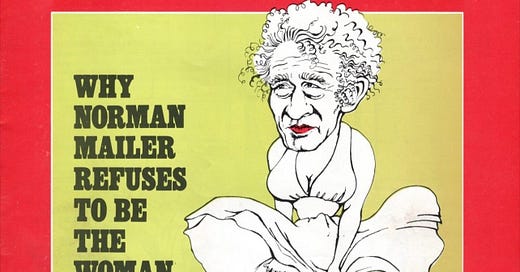

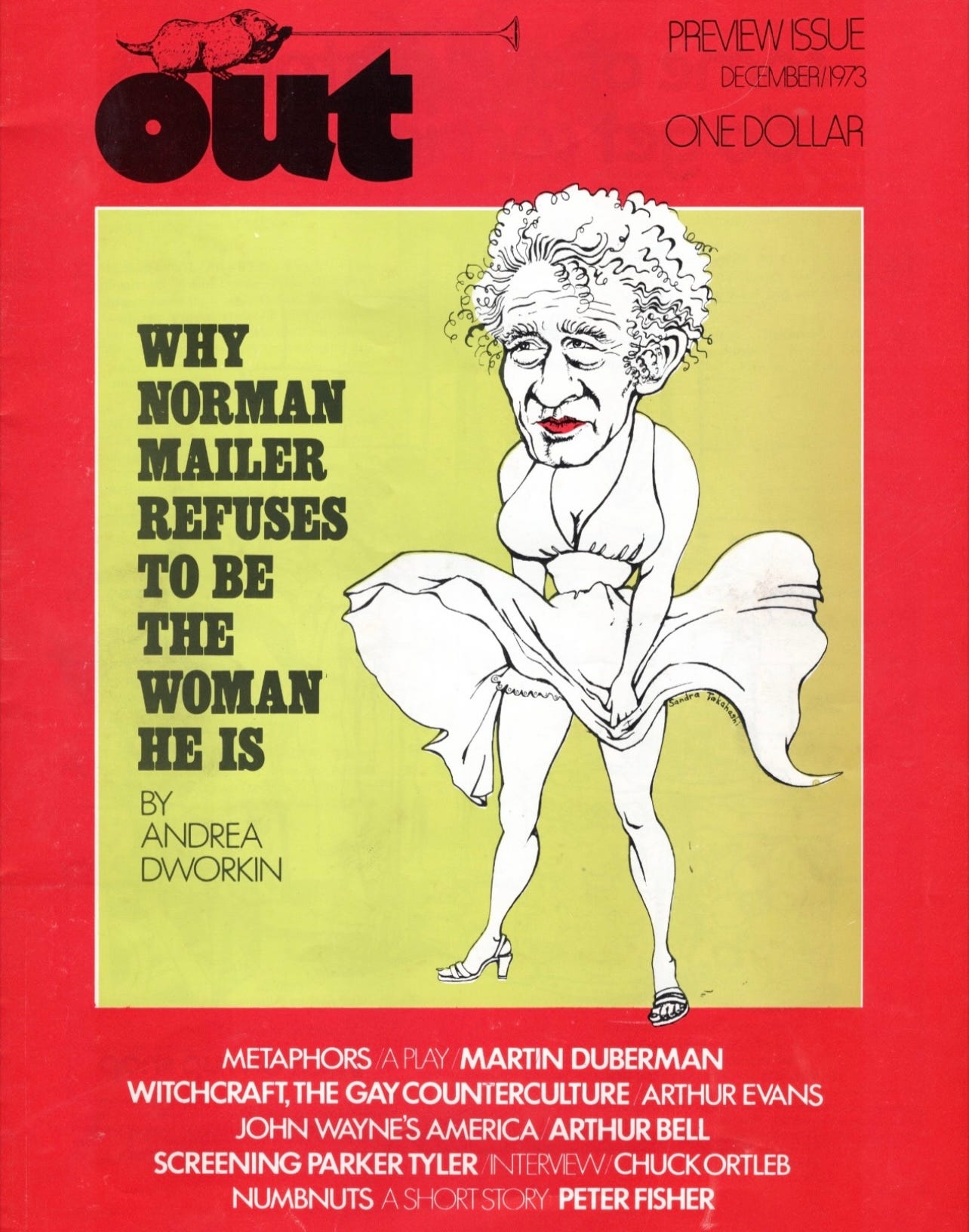

Andrea Dworkin’s “Why Norman Mailer Refuses to Be the Woman He Is” appeared in the preview edition of OUT magazine, published in December 1973. Preceding Dworkin’s Woman Hating: A Radical Look at Sexuality in 1974, this early work presents her developing analysis of sexual politics. In her critique of Mailer, Dworkin expresses disillusionment with him related to his book released at the time: Mailer’s 1973 “biography” of Marilyn Monroe. She describes Mailer’s Marilyn as his “newest religious tract on manhood, balling, and Amerika,” “Dorians twisted soul finally revealed.”9 His Marilyn, this statue made to his taste, tells the reader more about him than it does about her: a picture of the man in the woman according to his image.

Dworkin first read Mailer at the age of sixteen, and, through him, she writes, “learned to love sex and adventure.”10 Works like Mailer’s An American Dream (1965) appealed to the young Dworkin—then, at least. On her youthful love for “the mystique,” as Mailer fabricated it, Dworkin says she “had done the neat number of identifying with his male characters while living out the female scenario.”11 In her identification with men over women, Dworkin had not been a woman-identified woman but a man-identified woman. The male-defined values she had internalized from Mailer and the counterculture diverged from those more pronounced in Dworkin’s later philosophical thought.

This critique of Mailer focuses on how he has crafted the one-dimensional woman, who, in truth, reflects his own hollowness back at him. According to Dworkin, the man has artificed “a mystique of HIMSELF THE HERO AND HIS MANLINESS” (emphasis in original), “a continuing and endlessly repetitive saga of conquering and vanquishing the female foe.”12 By making (a) woman according to man’s image, Mailer possesses Marilyn; man possesses woman; he possesses her. Liberated from her love for Mailer, Dworkin writes:

when I understood that Mailer believed his women to be real women, and that therefore that did relate to me because of my biological womanhood, I was finally free—of the mystique, my place in it, and the love I had had for Norman Mailer. but one does not watch the death of an artist with detachment, one cannot abandon a teacher who has gone wrong, wronger, wrongest, without a great feeling of loss. and so, not surprisingly, I have thought a great deal about Mailer, and his art, and how he left it, and why.13

Through a male denial of female selfhood, in favor of their nonbeing, as Mailer constructs artifice in place of authenticity, he ironically negates himself at the moment of affirming his identity through female negation. In the process of seeking to possess womankind, his notion of making her “take it,” Mailer transitions, as Dworkin explains, “from rebellion and imagination to reaction and intransigence.”14 The former qualities, the rebellious and imaginative, are essential to the artist; the latter ones mean paralysis and death. Dworkin continues:

there is a terrible logic and symmetry to Mailers way of being in the world. he rejects the women who live inside his personality, and he would annihilate the women outside of him—deny them selfhood because he must deny that part of himself. he rejects those other bearers of the female stigma, male homosexuals, where they live in his own personality, and he is overtly hostile to those who live outside of his body—deny them selfhood because he must deny that part of himself. he has opted for a reactionary identity, and the security of a closed, narrowly-defined, sexually unambiguous persona.15

For Mailer, his sense of sex relative to the self has become an imprisoned expression of sex-role stereotyping, in the crudest sense—a great put-on, a drag, a minstrel show. Because he has bought stereotypes as the truth of sex, he has become a prisoner of it, the one-dimensional caricature Dworkin critiques revealed in Mailer’s Marilyn: his picture of Dorian Gray. The shell Mailer has crafted, which he sells as authentic, can never compare to what he could be, rather could have been—if he were to escape the bondage he mistakes for his freedom, were he to achieve being free of nonbeing. This “reactionary identity” comprises man’s attempt to seize from woman what Mary Daly has termed “the power of naming.”16 When female existence becomes the stuff of male fantasy, a state of his false being through her falsified nonbeing, it denies woman’s selfhood. Dworkin expanded her analysis of men possessing women in Pornography and Intercourse. Interestingly, more than Woman Hating, Dworkin’s essay partly foreshadows Dworkin’s pivot from a concern with androgyny and sexual repression, most evident in the last chapter of Woman Hating, to a sharper rejection of sexual liberalism present in her later works. Still, the idealism of androgyny and “pansexuality,” with such emphasis on “human liberation,” remains prevalent in Dworkin’s analysis of Mailer as it does at the end of Woman Hating.17

Androgyny into Sexual Liberalism

The sister was not a mister. Was this a surprise. It was. The conclusion came when there was no arrangement. All the time that there was a question there was a decision. Replacing a casual acquaintance with an ordinary daughter does not make a son.

- Gertrude Stein, Tender Buttons18

Martin Duberman briefly discusses Dworkin’s “Why Norman Mailer Refuses to Be the Woman He Is” in his Andrea Dworkin: The Feminist as Revolutionary (2020). Duberman’s brief discussion of Dworkin’s essay goes from a paragraph at the bottom third of one page onto the top of the next. He writes that “she did now and then give a speech or write an article centered on LGBTQ issues,” followed by a few quotations from Dworkin’s piece.19 Though, reading her article in full, it does not seem “centered on LGBTQ issues.” On what she describes as Mailer’s “androgyny” and “pansexuality,” Dworkin writes:

Mailer has abandoned his own androgyny, his own pansexuality. in creating the character he now plays in life, which is one-dimensional, rigid, and reductive, he has lost the ability to shift inside of himself into anything but caricature. […] one must get to the roots of the pansexuality in human formation to make great art. one could probably say that the greatest artists totally exploit their pansexuality, and that an artist is as great as his ability to do so, to undergo that rigorous, and often devastating, process.20

Here Dworkin’s analysis of Mailer closely resembles the one time “pansexuality” appears in Woman Hating, where she writes: “It is by developing one’s pansexuality to its limits (and no one knows where or what those are) that one does the work of destroying culture to build community.”21 While “pansexuality” appears once in the entirety of Woman Hating, only in the last chapter, it appears three times in Dworkin’s critique of Mailer, all used on the same page. Then cutting-edge, new, now overused and cliché, incorporated by the status quo of sexual liberalism, pansexuality used to be an idealized reorganizing of human sexuality, rethinking sex roles. Until Dworkin, among others, Mailer’s ideal—in his words, “[w]here a man can become more male and a woman more female by coming together in the full rigors of the fuck”—went unquestioned.22 Radical feminists responded by theorizing human alternatives beyond polarity, including “androgynous being” from Daly and “androgynous fucking” from Dworkin.23 Though falsely accused of thinking “all sex is rape,” Dworkin wrote, in 1974, that women and men can fuck, role-free, without the ancient trappings of submission and dominance that disfigure community between humans in favor of a culture of domination.24 Androgynous fucking, according to Dworkin, necessitated destroying, perhaps most significantly, “the personality structures dominant-active (‘male’) and submissive-passive (‘female’).”25 Transfiguring such personality structures into “gender identity,” essentially the same polarized roles made to be medicalized for high profit, of course, would undermine Dworkin’s ideal.

Reading the passage from Dworkin on Mailer’s abandonment of his androgyny leading to the inability to create great art, we may think of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, which, in 1929, idealized androgyny in similar terms. Woolf sketched a concept of the human soul, where “two powers preside, one male and one female; and in the man’s brain, the man predominates over the woman, and in the woman’s brain, the woman predominates over the man.”26 A symptom of how “masculinity” and “femininity” have been most successfully biologized, contemporary readers make the tragic mistake of believing Woolf was speaking literally instead of metaphorically. Woolf explained:

The normal and comfortable state of being is that when the two live in harmony together, spiritually co-operating. If one is a man, still the woman part of the brain must have effect; and a woman also must have intercourse with the man in her. Coleridge perhaps meant this when he said that a great mind is androgynous. It is when this fusion takes place that the mind is fully fertilised and uses all its faculties. Perhaps a mind that is purely masculine cannot create, any more than a mind that is purely feminine. (emphasis added)27

The use of “spiritually co-operating” matters in understanding that Woolf referred to a concept of the self quite akin to the concept of yin and yang in Chinese philosophy, where each person contains dark and light, feminine and masculine. In Woman Hating, Dworkin provides a valuable discussion of yin and yang against readings of polarization into female-as-feminine-as-dark-as-evil and male-as-masculine-as-light-as-good.28 In Woolf’s case, inspiration came from Samuel Taylor Coleridge, nearly a century earlier, in 1832, writing that “a great mind must be androgynous.”29 Thus, we can see Dworkin’s suggestion that “the greatest artists totally exploit their pansexuality” has its roots in Coleridge and Woolf idealizing the androgynous.

Among Dworkin’s contemporaries in the late 1960s and early 1970s, aside from Daly, we find a similar fascination with the possibility of androgyny. For instance, Betty Roszak’s “The Human Continuum” (1969) ended by suggesting “the woman in man” awaiting “her” emergence from within him would succeed women’s liberation.30 Another example was Carolyn G. Heilbrun’s Toward a Recognition of Androgyny (1973), with “the realization of man in woman and woman in man,” which, again, follows in similar fashion, though recognizing that we do not know what androgyny is.31 Interestingly, Heilbrun uncritically accepts Dionysus, the Greek god known for madness and boundary violation, as representing “[t]he unbounded and hence fundamentally indefinable nature of androgyny.”32

Similar to her contemporaries, Dworkin critiques the one-dimensional character of the “purely masculine,” or “that macho character,” for Mailer, seen in opposition to the “purely feminine.”33 Arguably more successful, more self-aware than Roszak and Heilbrun, even Woolf, Dworkin’s conceptual framework, then, at least attempted to resist the integration of androgyny, its co-optation, into male dominance and female subordination. Dworkin’s idealism of what Janice G. Raymond has termed “the illusion of androgyny” recurs in Woman Hating, as noted, and Our Blood: Prophecies and Discourses on Sexual Politics (1976), namely “The Root Cause,” a speech first delivered under the title “Androgyny” in 1975.34 However, this early theorizing, a distinct product of the first half of the seventies, lacks Dworkin’s later, far more critical perception of sexual liberalism evident in her future works.

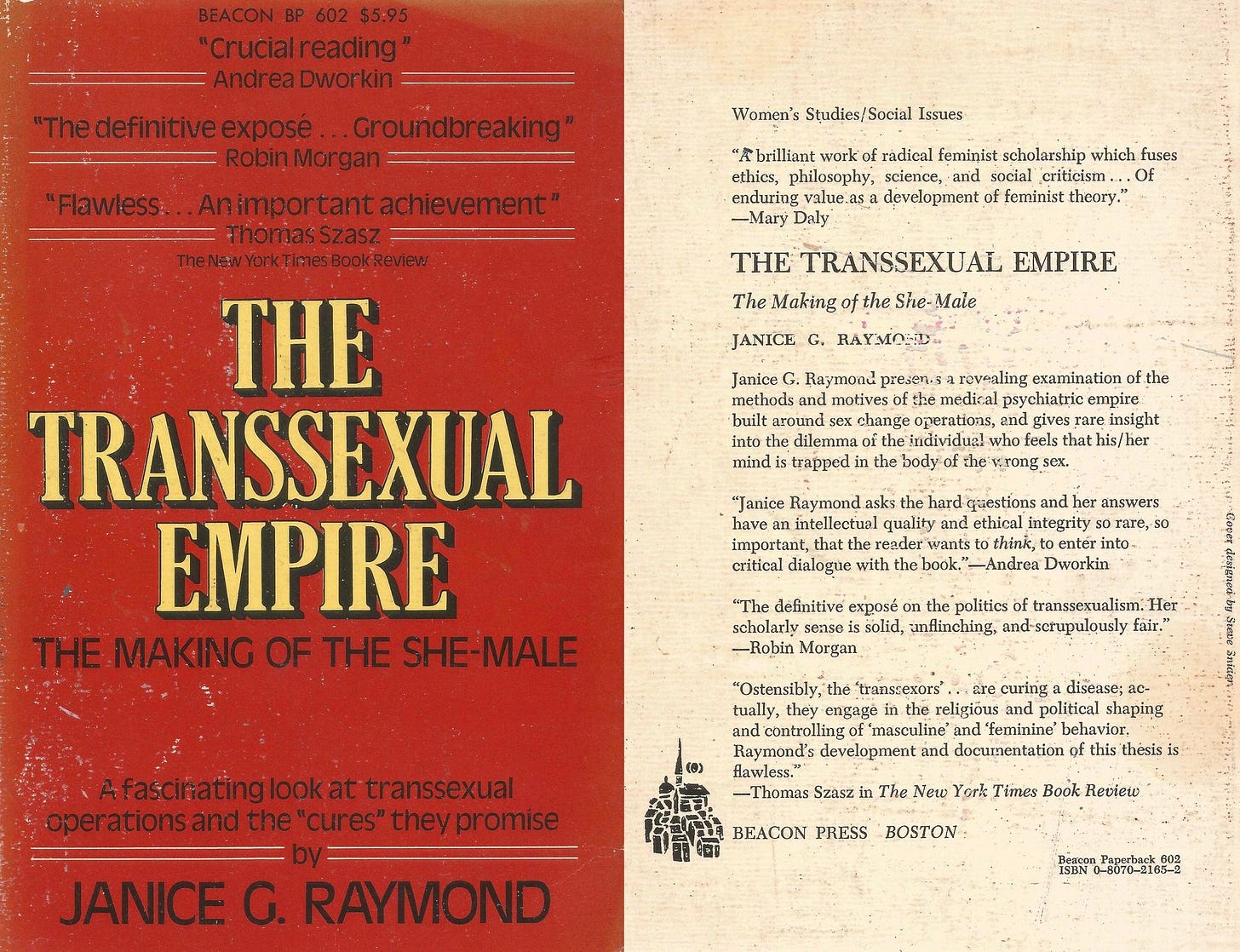

Reviled for critiquing transsexualism, Raymond’s The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male, in 1979, connected the liberal and “humanistic” notion of the “woman in man” with the growing backlash against women under sexual liberalism. In 1975, “The Illusion of Androgyny,” an early version of part of chapter six in Raymond’s Transsexual Empire, marked a continuing shift among radical feminists from idealizing androgyny, seen in Daly’s Beyond God the Father and Dworkin’s Woman Hating, to rethinking its meaning for women. Raymond underwent a shift in her own thinking, from “Beyond Male Morality” (1972), in which she had written, “Androgyny hopes to reunite that which has been separated.”35 Rethinking androgyny, however, Raymond later wrote:

Androgyny becomes the great leap forward, a synonym for an easily accessible human liberation that turns out to be sexual liberation—a state of being that men can enter as easily as women through the ‘cheap grace’ of the ‘wider’ countercultural revolution. What androgyny comes to mean here, in fact, is sexual revolution, phrased in the language of ‘The Third Sex.’ Sex (fucking), not power, becomes the false foundation of liberation.36

Half a century later, with far more heterosexual males declaring themselves “lesbians” and insisting their penises are “female” and that lesbians who do not desire them practice “biological superiority.” Androgyny cannot free women when the men always come first. Women submitted—many, not few—seduced by what, in The Transsexual Empire, Raymond describes as “the illusion of inclusion,” where devalued women appear valued by virtue of tokenism.37

Woman Hating exhibits Dworkin’s initial opposition to sexual repression and an idealism of androgyny toward human community, a theoretical orientation shared among radical feminists of the early seventies. By contrast, her subsequent work deals with the reality of men possessing women, most evident in Pornography and Intercourse. Similar to Raymond above, in Right-wing Women, Dworkin reflected on sexual liberation:

Empirically speaking, sexual liberation was practiced by women on a wide scale in the sixties and it did not work: that is, it did not free women. Its purpose—it turned out—was to free men to use women without bourgeois constraints, and in that it was successful. One consequence for the women was an intensification of the experience of being sexually female—the precise opposite of what those idealistic girls had envisioned for themselves.38

Men’s identification of themselves as “women,” especially “lesbians,” typically intensifies the experience of being sexually female for women, which—like prostitution and surrogacy—demonstrates the status of women as a colonized people.39 This desire to possess women’s bodies has primarily been the practice of the majority of heterosexual males who have used the minority of homosexual males—those like Christine Jorgensen—to suppress and dull women’s nagging sense of concern. Arguably, many women’s uncritical acceptance of men declaring themselves “women” has to do with the false assumption these men are mostly, if not exclusively, homosexual, neither heterosexual nor bisexual. Men possessing women in this way, however, presents consequences for all women, as a sex class, especially lesbians, whose freedom becomes constrained by men’s unconstrained “freedom of gender.” Returning to Dworkin’s Woman Hating, we may ask whether or not the heterosexual male’s identification of himself as a “woman” and a “lesbian,” androgyny manufactured through medical authority, actually facilitates liberating men like him from “the unfreedom of their fetishism.”40 How does this highly technologized form of men possessing women not, in a queerly Mailerian fashion, still result in man creating a definition of woman which serves him and which he will impose on woman?

Omitting as Forgetting

This which is mastered has so thin a space to build it all that there is plenty of room and yet is it quarreling, it is not and the insistence is marked.

- Gertrude Stein, Tender Buttons41

Thinking about it here, Duberman’s framing of Dworkin’s essay on Mailer being “centered on LGBTQ issues” corresponds with the way he and John Stoltenberg, among others, have performed what Nikki Craft has termed “editorial surgery on Dworkin’s sexual politics.”42 Duberman uncritically accepts Stoltenberg’s picture of Dworkin as a “trans ally,” as seen in Stoltenberg’s “Andrea Dworkin Was a Trans Ally” and its earlier version.43 As his evidence, Stoltenberg cites (1) the last chapter of Woman Hating (1974), (2) “The Root Cause” (1975), and (3) “Biological Superiority: The World’s Most Dangerous and Deadly Idea” (1977). There are, however, issues with Duberman’s portrayal of Dworkin worth raising—not interpretative, at the wholly subjective level, but pertaining to the act of omitting as forgetting.

“For a time in the seventies,” Duberman writes, Dworkin was “somewhat friendly with Janice Raymond, whose transphobic 1979 book The Transsexual Empire deplored the ‘medicalization’ of gender that encouraged surgical intervention to create ‘a woman according to man’s image.’”44 However, Dworkin’s friendship with Raymond continued after Raymond’s critique of Dworkin’s Woman Hating in 1977—of course, omitted by Duberman. In that critique, Raymond wrote:

Andrea Dworkin, in her otherwise insightful book Woman Hating, stated that until sex roles disappear (and thus also transsexualism), sex-change operations should be provided ‘by the community as one of its functions. This is an emergency measure for an emergency condition.’ […] With Dworkin, I would affirm that transsexualism is the result of the stereotyped sex roles of a rigidly gender-defined society. But is transsexualism really the ‘emergency answer to an emergency situation,’ or does it prolong the emergency? And is it the basic duty of ‘the community’ (presumably the feminist community) to provide such treatment?45

Most recently, in her 2021 book Doublethink: A Feminist Challenge to Transgenderism, refuting Stoltenberg, Raymond has added further context that “Dworkin only objected to my words ‘otherwise insightful.’”46 Even in Woman Hating, Dworkin noted that, again idealistically, “community built on androgynous identity will mean the end of transsexuality as we know it […] [A]s roles disappear, the phenomenon of transsexuality will disappear.”47 For Dworkin, transsexualism was transitory, not to be perpetuated, another part of her perspective that Stoltenberg and Duberman omit. “These words,” Raymond argues, “present a challenge to how Stoltenberg has channeled her views.”48 The more details we take into account, the more difficult it becomes to fit Dworkin’s perspective into the dominant “gender-affirming care” paradigm known today. Dworkin envisioned community between humans beyond gender polarity, which may be considered abolitionism in opposition to assimilationism. If we seek to abolish gender, then we cannot affirm it, socially or medically. No “trans ally” can be critical of social and medical transitioning, particularly conflicts for women and homosexual people, without now being condemned as “transphobic.”

Beyond Raymond’s 1977 critique, their collaborative relationship continued into Dworkin being acknowledged in relation to “Sappho by Surgery: The Transsexually Constructed Lesbian-Feminist” in The Transsexual Empire—so, more than “somewhat friendly.”49 In 1981, Dworkin acknowledged Raymond in Pornography among “people [who] helped me substantially,” listed with friends like Kathleen Barry, Gena Corea, and H. Patricia Hynes.50 With this acknowledgment, grouped among friends, Raymond’s Transsexual Empire also appeared in Dworkin’s bibliography, though not specifically discussed in the body of Pornography.51

Later, again contrasting Duberman’s characterization of their relationship as “somewhat friendly” during the seventies, Dworkin appears in the acknowledgments for Raymond’s 1986 A Passion for Friends: Toward a Philosophy of Female Affection. “The courage, work, and friendship of Andrea Dworkin, Robin Morgan, and Kathy Barry have been a source of inspiration and strength to me,” Raymond writes. “They remind me that radical feminism lives and thrives and that female friendship is indeed personal and political.”52 Raymond’s A Passion for Friends appears in the bibliography for Dworkin’s Intercourse in 1987, though, again, not specifically discussed.53

Into the 1990s, Raymond’s 1993 Women as Wombs: Reproductive Technologies and the Battle over Women’s Freedom includes Dworkin among “[o]ther friends [who] have helped in a variety of ways.”54 Finally, Raymond appears referenced positively by Dworkin in Scapegoat: The Jews, Israel, and Women’s Liberation, in 2000, related to Raymond’s work with the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women (CATW), with the proofs for Raymond’s Women as Wombs cited in Dworkin’s bibliography.55 Thus, available evidence, as provided here, indicates a long friendship between Dworkin and Raymond that extended to ongoing collaboration in their work. Duberman omits these details, which, if provided, would undermine his claims.

Raymond’s critique of transsexualism, Duberman writes, “was a view that Andrea deplored, and she let Raymond know it at some length” (p. 161). As his evidence, Duberman cites a letter Dworkin wrote to Raymond about trans-identified people, dated January 15, 1978, in which she clarified her perception of “their suffering as authentic.”56 According to her letter, Dworkin had empathy for males “in rebellion against the phallus” and females “seeking a freedom only possible to males in patriarchy.” She continued to be empathetic toward others’ suffering, an empathy also shared by very many concerned feminists condemned as “TERFs”: “trans-exclusionary radical feminists.” I would argue, however, that females and males with whom Dworkin felt the greatest sense of connection were most likely not the majority of heterosexual people transitioning but the minority of homosexual ones.

Heterosexual males claiming possession of female and lesbian bodies, especially men declaring their penises “girl dicks,” now the majority, would not qualify under Dworkin’s criteria of being “in rebellion against the phallus.” Was Dworkin’s vision for a majority of cross-dressing straight men addicted to pornography and body modification further enforcing male entitlement onto women and lesbians? About half a century can make a big difference, which seems worth acknowledging. The sexual revolution, as Dworkin agreed with Mailer, “had gotten into the hands of the wrong people,” but those people, of course, happened to be men.57 Now, the transgender revolution seems to be a parallel in freeing men to use women, again intensifying the subordination of women. How can the social and medical transitioning of children, enforcing the gender polarity Dworkin truly deplored, move us toward what Duberman phrases as “Andrea’s dream of a gender-just world”?58 Such a world, as Dworkin envisioned it, would surely not involve putting children on “puberty blockers,” extensively medicalizing them due to their lack of conformity to gendered expectations. Speaking in the concrete, not the abstract, gets at some truth beyond the superficial uses of “trans ally” and “gender-affirming care” stupefying these discussions. Hollow appeals to “allyship” and “affirmation,” conveniently used to muzzle noncompliant women, sidestep the hard questions about ethics.

Though Duberman cites Dworkin’s 1978 letter to Raymond, likely a response to Raymond’s 1977 critique of Dworkin that Duberman omits, he also omits Dworkin’s book endorsement for Raymond’s Transsexual Empire in 1979. On Raymond’s book, a text which includes a critique of androgyny, again reflecting a shift in radical feminist philosophy, Dworkin writes:

Janice Raymond asks the hard questions and her answers have an intellectual quality and ethical integrity so rare, so important, that the reader wants to think, to enter into critical dialogue with the book.59

Very interestingly, in a reply to Cristan Williams, dated May 1, 2014, from the archived version of Stoltenberg’s original Feminist Times piece, he quotes Dworkin’s blurb saying “Crucial reading” but omits the full text of her book endorsement.60 To Williams’ question, which he says Stoltenberg asked him to ask, Stoltenberg provides a convoluted explanation, asserting that Dworkin “never retracted” her views put forth in Woman Hating. His attempt at explaining himself includes the interesting claim that he and Dworkin agreed with Raymond’s Transsexual Empire on surgical and hormonal interventions—except, somehow, this same medicalization, now far more widespread than in 1979, no longer reinforces gender polarity. He says, “We did not foresee that upon publication the book would become anathema to trans people—for some of whom those selfsame surgical/hormonal inventions would be beneficial and necessary.” To date, Williams has not questioned Stoltenberg’s otherwise questionable explanation and has published writings like “Radical Inclusion: Recounting the Trans Inclusive History of Radical Feminism” (2016).61 Misrepresentation breeds misrepresentation. I would argue the more complex portrait of Dworkin would bring about integrity, real thought, and critical dialogue, none of which occur when misrepresenting women in favor of how those women exist in men’s imaginations. Like Mailer, Stoltenberg, “has created definitions which serve him, and he will impose those definitions on all manner of experience because they serve him.”62 Mailer is to Marilyn as Stoltenberg is to Dworkin.

Interviewed by Cindy Jenefsky in 1989, Dworkin “noted that even though feminists and pornographers were moving in different directions at the time Woman Hating was written, they still shared common roots in the counterculture and the sexual liberation movement.”63 Again, we must remember that the Dworkin of the seventies continued to diverge from the sexual values she internalized from the counterculture and the sexual revolution. During the same interview with Jenefsky, Dworkin said, “I think there are a lot of things really wrong with the last chapter in Woman Hating.”64 For reference, the last chapter of Woman Hating, referred to by Dworkin in her statement, begins on page 174 and ends on page 193. The section titled “Transsexuality” starts at the very bottom of page 185 and ends at the very top of page 187. Of course, Duberman also omits Dworkin’s statement on there being “a lot of things really wrong with the last chapter in Woman Hating.” Though Duberman includes Jenefsky’s book listed among sympathetic readings of Mercy, her 1990 novel, he does not engage with Dworkin’s regret years later over the last chapter of Woman Hating and the implications for citing it as representative of what her views would be.65 Again, had Duberman provided certain omitted evidence to the reader, as detailed here, it would have undermined his and Stoltenberg’s picture of Andrea Dworkin. To quote Woman Hating, “The body must be freed, liberated, quite literally: from paint and girdles and all varieties of crap.”66 Like the woman in Kōbō Abe’s 1962 novel Woman in the Dunes, Dworkin lived in her body and, in death as in life, does not live in any man’s imagination, is no man’s statue.

Omitting as forgetting disfigures the imagination, distorting artificiality into authenticity. To resist, the reader with integrity must insist on actively repeating it all. Apart from the above issues, Duberman incorrectly dates the OUT article as “August 1973,” but it was part of the December 1973 preview issue.67 From her papers, Dworkin’s manuscript, prior to publication, has the date “August 1973,” presumably the text as submitted for print in OUT’s forthcoming December issue. These may seem like minor details on time, but even a few months can make a world of difference, though like moments read on the page.

insisting on marking against omitting as forgetting

What did she do with fire. She almost put fire to forensics. As useful. As usual. As vagrant. As appointed. As veiled. And as welcome. In their plenty. This may be there. And they will dwell upon it.

- Gertrude Stein, How to Write68

before there was Andrea Dworkin, there was Gertrude Stein, this other most unconventional woman, who remained an influence on Dworkins style in the more experimental forms it took—tenderly so. because structures beyond the text must be changed, done with a marked difference, she experimented with the structure of the text, making it feel different to the reader. Steins writing worked this way, structured by what may appear to be repetition while really being insistence, for writing as remembering works this way, insisting on something against omitting as forgetting.

looking at the writing, the engaged text looks unconventional, like creating as composing, looking quite unlike much writing from the corporate publishing house. Dworkins essay on Mailers MARILYN follows the style articulated in the afterword to her WOMAN HATING on “the great punctuation typography struggle”: “lower case letters, no apostrophes, contractions.”69 book reviewers dislike so many lower case letters, preferring the capitalization there. per her style, Dworkin, however, intended to have the book “be as empty as possible,” only punctuated by necessity, little as there would be.70 nothing more would be needed than how the look of the text would engage with the reader.

Dworkin practiced saving the sentence, the fire there, in this most Steinian way, and this practice seems most pleasing—to me, at least, done so this way—violently, delightfully so. as it appeared in December 1973, Dworkins essay appears to have the same arrangement as her manuscript dated August 1973. though I do not have immediate access to her papers, as Duberman did, it would be likely her essays publication in OUT was a rare time her writing appeared unmodified. setting her manuscript beside the published version, there seem to be no changes to content, organization, and form, down to the typographical level—unmolded by another. that “Immovable Punctuation Typography Structure,” as Dworkin termed it, seems relatively less insistent than the “Immovable Sexual Structure,” still possessing, yes, but insisting less so.71 under similar peculiar social conditions, a disparity of fire, the forgetting of the body as it should flourish, text changes nevertheless differ significantly from sex changes. with both, however, lying as surviving becomes mistaken for a flourishing human life. not coincidentally, even ironically, one may find it remarkably costly to live crap-free living being.

Man-Made Artifacts, Man-Made Abstractions

Really realising this thing, completely realising this thing is the disillusionment in living is the beginning of being an old man or an old woman is being no longer a young one no longer a young man or a young woman no longer a growing older young man or growing older young woman.

- Gertrude Stein, The Making of Americans72

Dworkin was a woman who learned for her life against the supposed “givens,” including those of the “radical” left revealed as not so radical—at least, when politics concerns women. She experienced what may be termed serial disillusionment over typical male artificers—icons—from whom she drew great inspiration in art—two striking examples being Mailer, as discussed here, and, of course, Allen Ginsberg.73 Other literary influences were D.H. Lawrence and Henry Miller, both of whom she also grew disenchanted with, much as Mailer looked different—not rebellious and courageous but impotent and fearful—after she looked at him again. Dworkin’s body of work insists that we think and, in so doing, think again, even more, in moving toward integrity, not merely into the collaboration of integration. What has been left out, that unremarked but remarkable, is what must be found, beyond “the given.”

Let us consider Last Days at Hot Slit: The Radical Feminism of Andrea Dworkin, edited by Johanna Fateman and Amy Scholder in 2019. Fateman and Scholder titled the collection Last Days at Hot Slit on the basis of a postcard, dated April 3, 1973, that Dworkin sent to her parents saying “the book will be called LAST DAYS AT HOT SLIT,” having “just settled on that title.”74 With Fateman and Scholder, presumably also with Stoltenberg in agreement, Duberman affirms Last Days at Hot Slit as “the original title” for Woman Hating, no mention of anything else.75 The reader may presume Last Days at Hot Slit was the only title prior to the book’s renaming as Woman Hating. If so many say it must be so, then so it must be—many would like to think, at least, much easier that way, less of a voyage to undertake, avoiding that more adventurous challenge and the rigor of really thinking.

Of course, they would be right, unquestionably so, if they were not wrong, or, at least questionable in the conclusions drawn from partiality—Dworkin’s portrait left incomplete. Reading “Why Norman Mailer Refuses to Be the Woman He Is,” the published version dated December 1973, we find another title. In OUT, a couple of lines about the author read, “Ms. Dworkin’s book, Freedom or Death, will be published by E.P. Dutton in April, 1974. She is currently working on a book about prisons.”76 Again, we find these missing pieces, fragments, marked parts of the picture, excluded from documentation, left unremarked, strangely, but telling us more than we have been told. Never able to be whole, a portrait becomes partialized in omitting as forgetting. If Freedom or Death had been known as the final working title, prior to the very last change to Woman Hating, then none of those mentioned above mention it as such. One may wonder, as I do, why not speak of Freedom or Death, what Dworkin apparently settled on after having “settled on” Last Days at Hot Slit. While Last Days at Hot Slit was a working title, even if “the original title,” it seems Freedom or Death became the intended title before Woman Hating.

Woman Hating’s title, at least as Dworkin last intended, was not Last Days at Hot Slit, only the earliest known, all else being omitted, but Freedom or Death, a title worthy of a more engaging collection of her works. Unmentioned, Dworkin’s choice here most likely alluded to Emmeline Pankhurst, the English suffragette, who delivered a speech of the same name in Hartford, Connecticut, on November 13, 1913.77 Christabel and Sylvia Pankhurst, Emmeline Pankhurst’s daughters, appear in Dworkin’s Pornography, influencing it as Elizabeth Cady Stanton influenced Right-wing Women.78 One must remember freedom, if only to keep the artist’s vision of what life could be were the world different—if the structure did not press, depress, the way it does in disembodying us. We should remember death and why so many women do become as disillusioned as Dworkin with the men they so dearly love and why such revolutions make only more of the same.

Learning for one’s life necessitates, as Dworkin put it, not only creating but also engaging “a living world with all of its contradictions, tensions, and discrete personalities.”79 For her, the artist does not inhabit others, possessing and colonizing them, as Norman Mailer did to Marilyn Monroe. Art requires artists living with difference, within the body as the self, not to be negated by false affirmation. “Touch, then, becomes what is distinctly, irreducibly human; the meaning of being human,” Dworkin writes in Intercourse. “This essential human need is met by an equal human capacity to touch, but that capacity is lost in a false physical world of man-made artifacts and a false psychological world of man-made abstractions.”80 Perhaps this point, what I have learned from Dworkin past to present, this living being in one’s body and understanding others, has been widely neglected for half a century too long.

If you are unable to become a paid subscriber through Substack, then please feel free to donate via PayPal, if able. I am grateful for reader support!

Further Reading

Here are selected appearances of Mailer in Dworkin’s writing following her 1973 critique:

Woman Hating: A Radical Look at Sexuality (New York: Plume, 1974), 75, 83, 86.

“Feminism, Art, and My Mother Sylvia” (1974/1975), Our Blood: Prophecies and Discourses on Sexual Politics (New York: Perigee Books, 1976/1981), 9.

“The Rape Atrocity and the Boy Next Door” (1975), Our Blood, 29.

“First Love” (1978/1980), in The Woman Who Lost Her Names: Selected Writings of American Jewish Women, ed. Julia Wolf Mazow (San Francisco: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1980), 125, 128.

Right-wing Women: The Politics of Domesticated Females (New York: Perigee Books, 1983), 18, 37, 41-43, 88, 189.

Intercourse (New York: Basic Books, 1987/2007), 193-196.

Mercy (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1990/1992), 84-85, 88, 112, 117.

“Women in the Public Domain” (1992), Life and Death: Unapologetic Writings on the Continuing War Against Women (New York: The Free Press, 1997), 202-203.

Scapegoat: The Jews, Israel, and Women’s Liberation (New York: The Free Press, 2000), 195.

Heartbreak: The Political Memoir of a Feminist Militant (London: Continuum, 2002/2006), 34-35, 93-94.

Here are secondary writings about Dworkin for reference:

Cindy Jenefsky, with Ann Russo, “Quest for Alternative Scripts,” chap. 3, in Without Apology: Andrea Dworkin’s Art and Politics (New York: Routledge, 1998/2018), 37-45.

Martin Duberman, Andrea Dworkin: The Feminist as Revolutionary (New York: The New Press, 2020), 13-14, 73-74, 161, 297-298, 309.

Janice G. Raymond, Doublethink: A Feminist Challenge to Transgenderism (Mission Beach, Australia: Spinifex Press, 2021), 41-47.

Andrea Dworkin, Intercourse (New York: Basic Books, 1987/2007), 36. This passage comes from one of my favorite parts of Intercourse, where Dworkin writes about Kōbō Abe’s Woman in the Dunes (1962).

Dworkin, “Women in the Public Domain: Sexual Harassment and Date Rape” (1992), in Life and Death: Unapologetic Writings on the Continuing War Against Women (New York: The Free Press, 1997), 203.

Dworkin, Right-wing Women: The Politics of Domesticated Females (New York: Perigee Books, 1983), 88.

Norman Mailer, The Prisoner of Sex (New York: Donald I. Fine, Inc., 1971/1985), 171-173. Even when they varied in their positions on Millett’s Sexual Politics, the reviews of Mailer’s Prisoner of Sex foreshadowed Dworkin’s 1973 verdict on Mailer as “a rebel [who] is now a reactionary,” “a very sophisticated hack” (p. 10). See Annette Barnes, “Norman Mailer: A Prisoner of Sex,” The Massachusetts Review 13, no. 1/2, Woman: An Issue (Winter-Spring 1972), 269-274; Janel M. Mueller, review of The Prisoner of Sex, by Norman Mailer, Theology Today 28, no. 2 (March 1971): 237-242; Bobbie Goldstone, “Norman, Prisoner of Sex,” off our backs 1, no. 19 (March 25, 1971): 6; Brigid Brophy, “Meditations on Norman Mailer, by Norman Mailer, Against the Day a Norman Mailest Comes Along,” The New York Times, May 23, 1971, BR1, BR14-BR15; and Jonathan Raban, “Huck Mailer and the Widow Millett,” New Statesman 82 (September 3, 1971): 303-304.

Mailer, Marilyn: A Biography (London: Virgin Books, 1973/2012), 56-57.

Mailer, Genius and Lust: A Journey Through the Major Writings of Henry Miller (New York: Bantam Books, 1976/1977), 155.

Dworkin, “Why Norman Mailer Refuses to Be the Woman He Is,” OUT, preview issue, December 1973, 12.

Gertrude Stein, How to Write (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 1931/2018), 386.

Dworkin, “Why,” 10.

Dworkin, 10.

Dworkin, 11.

Dworkin, 11.

Dworkin, 11-12.

Dworkin, 10.

Dworkin, 12.

Mary Daly, Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation (Boston: Beacon Press, 1973/1985), 8.

For a further discussion of how Dworkin goes beyond Woman Hating, as Daly went beyond Beyond God the Father, see Cindy Jenefsky, with Ann Russo, “Quest for Alternative Scripts, chap. 3, in Without Apology: Andrea Dworkin’s Art and Politics (New York: Routledge, 1998/2018), 37-45.

Stein, Tender Buttons (1914), in Selected Writings of Gertrude Stein, ed. Carl Van Vechten (New York: Vintage Books, 1962/1990), 499-500.

Martin Duberman, Andrea Dworkin: The Feminist as Revolutionary (New York: The New Press, 2020), 73.

Dworkin, “Why,” 12.

Dworkin, Woman Hating: A Radical Look at Sexuality (New York: Plume, 1974), 185.

Mailer, The Prisoner of Sex, 171.

See “androgynous being” in Daly, Beyond God the Father, 36, 41-42, 50, 169, 172, 191; see “androgynous fucking” in Dworkin, Woman Hating, 184-185.

See Katharine Viner, “‘She Never Hated Men,’” The Guardian, April 12, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2005/apr/12/gender.highereducation.

Dworkin, Woman Hating, 185.

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (San Diego: Harcourt, Inc., 1929/1989), 98.

Woolf, 98.

See Dworkin, Woman Hating, 164-167.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, September 1, 1832, in Specimens of the Table Talk of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1836), 2nd ed., ed. Henry Nelson Coleridge, vol. 14, The Collected Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. Carl Woodring (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 190-191.

Betty Roszak, “The Human Continuum,” in Masculine/Feminine: Readings in Sexual Mythology and the Liberation of Women, ed. Betty Roszak and Theodore Roszak (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1969), 306.

Carolyn G. Heilbrun, Toward a Recognition of Androgyny (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1973/1993), 167.

Heilbrun, xi.

Dworkin, “Why,” 12.

See Janice G. Raymond, “The Illusion of Androgyny,” Quest: a feminist quarterly 2, no. 1 (Summer 1975): 57-66; reprinted in Building Feminist Theory: Essays from Quest: a feminist quarterly (New York: Longman, 1981), 59-66; see also Raymond, “Toward the Development of an Ethic of Integrity,” chap. 6, in The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male (New York: Teachers College Press, 1979/1994), 154-168. For another feminist critique of androgyny, see Mary Daly, Gyn/Ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism (Boston: Beacon Press, 1978/1990), 387-388; see also Daly, Pure Lust: Elemental Feminist Philosophy (Boston: Beacon Press, 1984), 207-209, 341.

Raymond, “Beyond Male Morality,” in Women and Religion, revised edition, ed. Judith Plaskow and Joan Arnold (Missoula, MT: Scholars Press, 1972/1974), 124.

Raymond, The Transsexual Empire, 162. A slightly edited version of this passage, an earlier version of it, can be found in Raymond, “The Illusion of Androgyny,” 62.

Raymond, 27.

Dworkin, Right-wing Women, 91.

See Robin Morgan, “On Women as a Colonized People” (1974), in Going Too Far: The Personal Chronicle of a Feminist (New York: Vintage Books, 1977/1978), 160-162. See also Morgan, “On Women as a Colonized People” (1974), in Radical Feminism: A Documentary Reader, ed. Barbara A. Crow (New York: New York University Press, 2000), 471-472.

Dworkin, Woman Hating, 116.

Stein, Tender Buttons, 505.

Nikki Craft, “Altering Andrea: How John Stoltenberg Performs Editorial Surgery on Dworkin’s Sexual Politics,” Facebook, March 7, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/notes/966306530564695.

See John Stoltenberg, “Andrea Dworkin Was a Trans Ally,” Boston Review, April 8, 2020, https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/john-stoltenberg-andrew-dworkin-was-trans-ally. For the earlier version of this argument, with particularly interesting comments, see Stoltenberg, “Andrea Was Not Transphobic,” Feminist Times, April 28, 2014, https://web.archive.org/web/20180801010005/http:/archive.feministtimes.com/%E2%80%AA%E2%80%8Egenderweek-andrea-was-not-transphobic.

Duberman, Andrea Dworkin, 161.

Raymond, “Transsexualism: The Ultimate Homage to Sex-Role Power,” Chrysalis 3, 1977, 11-12.

Raymond, Doublethink: A Feminist Challenge to Transgenderism (Mission Beach, Australia: Spinifex Press, 2021), 46.

Dworkin, Woman Hating, 186-187.

Raymond, Doublethink, 46.

Raymond, The Transsexual Empire, viii.

Dworkin, Pornography: Men Possessing Women (New York: Plume, 1981/1989), 225.

Dworkin, 268.

Raymond, A Passion for Friends: Toward a Philosophy of Female Affection (North Melbourne, Australia: Spinifex Press, 1986/2001), ix.

Dworkin, Intercourse, 293.

Raymond, Women as Wombs: Reproductive Technologies and the Battle over Women’s Freedom (Mission Beach, Australia: Spinifex Press, 1993/2019), xiv

Dworkin, Scapegoat: The Jews, Israel, and Women’s Liberation (New York: The Free Press, 2000), 329, 407.

Dworkin, quoted in Duberman, Andrea Dworkin, 161.

Dworkin, Right-wing Women, 88.

Duberman, dedication, Andrea Dworkin, n.p.

Dworkin, book endorsement, The Transsexual Empire, back cover.

Stoltenberg, May 1, 2014, comment, Stoltenberg, “Andrea Was Not Transphobic,” Feminist Times, April 28, 2014, https://web.archive.org/web/20180801010005/http:/archive.feministtimes.com/%E2%80%AA%E2%80%8Egenderweek-andrea-was-not-transphobic.

See Cristan Williams, “Radical Inclusion: Recounting the Trans Inclusive History of Radical Feminism,” Transgender Studies Quarterly (TSQ) 3, nos. 1-2 (May 2016): 254-258. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-3334463. See also Williams, “The Ontological Woman: A History of Deauthentication, Dehumanization, and Violence,” The Sociological Review 68, no. 4 (July 2020): 718-734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120938292. Williams misapplies Dworkin’s 1977 critique “Biological Superiority: The World’s Most Dangerous and Deadly Idea” to argue that women not seeing men as women is “biological superiority.”

Dworkin, “Why,” 12.

Cindy Jenefsky, with Ann Russo, Without Apology: Andrea Dworkin’s Art and Politics (New York: Routledge, 1998/2018), 139.

Dworkin, quoted in Jenefsky, 139.

Duberman, Andrea Dworkin, 321, note 10.

Dworkin, Woman Hating, 116.

Duberman, 299, note 23.

Stein, How to Write, 386.

Dworkin, Woman Hating, 197.

Dworkin, 197.

Dworkin, 203.

Stein, The Making of Americans: Being a History of a Family’s Progress (1925), in Selected Writings of Gertrude Stein, ed. Carl Van Vechten (New York: Vintage Books, 1962/1990), 301.

See Donovan Cleckley, “When Andrea Dworkin Told Pedophile Beat Poet Allen Ginsberg She Wanted Him Dead,” The Distance, May 21, 2023, https://www.thedistancemag.com/andrea-dworkin-told-child-molesting. Following my introduction, Craft and I included a transcript of the conversation she had with Dworkin on May 9, 1990. We were delighted to have shared it to the ADAP page on May 9, 2023, followed by The Distance reprinting our work. See Andrea Dworkin Archival Project (ADAP), Facebook, May 9, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/share/GzPpaEB7d222N8EL.

Dworkin, “Postcard to Mom and Dad” (April 3, 1973), in Last Days at Hot Slit: The Radical Feminism of Andrea Dworkin, ed. Johanna Fateman and Amy Scholder [South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2019], 43.

Duberman, 297.

Dworkin, “Why,” 11.

See Emmeline Pankhurst, “When Civil War Is Waged by Women,” in Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings, ed. Miriam Schneir (New York: Vintage Books, 1972/1994), 296-304. See also Emmeline Pankhurst, “Freedom or Death” (November 13, 1913), The Guardian, April 27, 2007, https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2007/apr/27/greatspeeches. For a discussion of Pankhurst’s speech and the unfortunate end of this civil war by negotiation, see Germaine Greer, “Germaine Greer on Emmeline Pankhurst’s Extraordinary ‘Freedom or Death’ Speech,” The Guardian, April 26, 2007, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/apr/27/emmeline-pankhurst-freedom-or-death-introduction.

See Dworkin, Pornography, preface (n.p.) (Christabel Pankhurst, “The Government and White Slavery,” 1913), 102-103, 227, 231, 267, 283; Dworkin, Right-wing Women, book epigraph (n.p.) (Elizabeth Cady Stanton, “The Solitude of Self,” 1892), 59, 174, 190, 243.

Dworkin, “Why,” 12.

Dworkin, Intercourse, 36.