On Grief

Some reflections one year after Momma’s passing

One year after Momma’s passing, this piece is a shorter one reflecting on grief with Elizabeth Barrett Browning, one of my favorite nineteenth-century poets.

Within the next few weeks, I will be having some new posts featuring some curated pieces from women’s history, including some further selections from Mary Wollstonecraft and Victoria Woodhull on women’s experiences with motherhood and marriage.

In Substack news, for all subscribers, I plan on beginning a sort of book club for discussion of historical texts in light of contemporary issues. Work at the laundromat and the minimart with my father has gone relatively well, so I want to plan Zoom sessions, if not before the start of the year, then into January 2026. My thinking is to limit the book club to paid subscribers, as some incentive, perhaps having a few select “open” sessions, depending on interest (and my sanity). I would like to look at both older texts and more recent ones—for instance, Janice G. Raymond’s 1979 Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male read with Helen Joyce’s 2021 Trans: When Ideology Meets Reality. Sessions would include works from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and their relevance to how we approach today’s problems.

Touch it: the marble eyelids are not wet.

If it could weep, it could arise and go.

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning, “Grief,” 18421

Months like November and December can be especially difficult after the passing of a loved one, such times when families gather and those missing become sharply noticeable more painfully so than other times.

I remember the point where, talking with doctors, it seemed impossible that Momma would make a recovery, as her infection from vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE) led her into sepsis again since major abdominal surgery late that August.

Over those weeks, from late November into early December, I sat watching the screens of medical technology, seeing numbers improve, at first, and then drastically swing into an increasingly hopeless direction.

When the doctors came around, I tried my best to hold myself together, but, closer to the end, I kept choking with sobs when I would speak with them, sometimes unable to use words—as the ventilator deprived Momma of her last utterances.

I held her hand and kissed it, with my tears falling onto her skin.

There were recordings and pictures in the last months of Momma’s life that I still cannot revisit without unbearable pain.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s 1842 poem “Grief” describes “everlasting watch and moveless woe” that characterize the paralysis of grief—making us the living into monuments to the dead.

I never tell anybody that grief lessens or becomes easier; it becomes manageable, yes, even somewhat livable.

I remember writing a note to the doctors and nurses at Grandview thanking them and saying that we tried, thanking the young Nurse S., who prayed and cried with me, and the motherly Nurse K., who hugged me and was there for Momma’s last day.

There was a nurse who cared about Momma like one would care for a mother or a grandmother—and came to see Momma and left a rose on her chest.

Other sharp moments have faded over the last year, perhaps for the best now, but visions return, sad and happy, grief with hope.

Here is my post from December 3, 2024, one year ago:

Vickie Cleckley, forever beloved Momma to me, passed away this afternoon, surrounded by her family and loved ones. Days and nights, I stayed by her side, sleeping in the hospital room and watching over her—refusing to leave. Momma is free.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, “Grief,” 1842

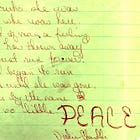

I tell you, hopeless grief is passionless;

That only men incredulous of despair,

Half-taught in anguish, through the midnight air

Beat upward to God’s throne in loud access

Of shrieking and reproach. Full desertness

In souls as countries, lieth silent-bare

Under the blanching, vertical eye-glare

Of the absolute Heavens. Deep-hearted man, express

Grief for thy Dead in silence like to death:—

Most like a monumental statue set

In everlasting watch and moveless woe,

Till itself crumble to the dust beneath.

Touch it: the marble eyelids are not wet.

If it could weep, it could arise and go.

If you are unable to become a paid subscriber through Substack, then please feel free to donate via PayPal, if able. I am grateful for reader support!

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, “Grief,” 1842, in Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Selected Poems, eds. Marjorie Stone and Beverly Taylor (Ontario, Canada: Broadview Press, 2009), 99.