Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication

Wollstonecraft’s “revolution in female manners” against “the tyranny of man”

This piece introduces Wollstonecraft’s 1792 A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, an early work in feminist philosophy, with selections from her book. A problem facing today’s readers has been selective quotation producing a misrepresentation of Vindication, which, I argue, has led to varieties of retardation in modern feminism. For instance, here is the most popular line, seen on Goodreads: “I do not wish [women] to have power over men; but over themselves.” Read in context, however, Wollstonecraft critiques what she calls “the tyranny of man” and women’s submission to it, including women and men alike becoming vicious that women may “obtain illicit privileges.” Considered with Dworkin’s 1973 “Marx and Gandhi Were Liberals—Feminism and the ‘Radical’ Left,” Wollstonecraft’s Vindication demonstrates a continuity in the feminist analysis of power. After my introduction, I have provided selections from all thirteen chapters of Vindication. There is a “Further Reading” section at the end with texts that can be helpful alongside reading Wollstonecraft.

The Revolution thus was not merely an event that had happened outside her; it was an active agent in her own blood. She had been in revolt all her life—against tyranny, against law, against convention. The reformer’s love of humanity, which has so much of hatred in it as well as love, fermented within her.

- Virginia Woolf, “Mary Wollstonecraft,” The Nation and Athenæum 46, no. 1, October 5, 19291

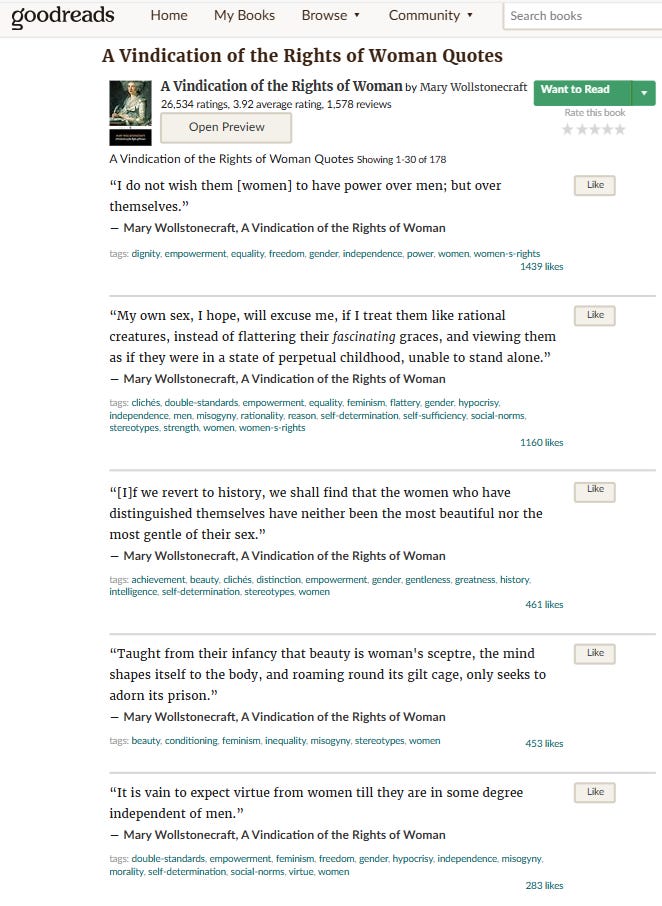

Looking at Goodreads, the most liked quote in Wollstonecraft’s Vindication happens to be the following: “I do not wish [women] to have power over men; but over themselves” (p. 133). Divorced from its original context, this quote becomes a variation of “pull oneself up by one’s own bootstraps”—but for women. Ironically, the original line is Wollstonecraft responding to Rousseau quoted in the same paragraph: “Educate women like men and the more they resemble our sex the less power will they have over us” (emphasis added). According to Rousseau, women’s “power” over men can be measured in men’s desire for them in their lack of resemblance to men, their otherness in their femininity—essentially, women bartering their sexuality for influence over men. Read in context, Wollstonecraft critiques the idea that women must barter their sexuality for “power” over men and, instead, argues for women’s self-possession and real power over themselves in a selfhood not measured by women’s sexual desirability relative to men. So, the most widely quoted line also happens to be the most widely misinterpreted one quoted without reference to Wollstonecraft responding to Rousseau. Within the top five Goodreads quotes listed, among the snippets from Vindication, there is the one about women being taught of beauty as “woman’s sceptre” (p. 112). Scrolling the page of quotes, however, we do not clearly see Wollstonecraft’s analysis of power as much as the readers’ emphasis on liberal individualism in the most palatable bits. Vindication’s radicalism disappears.

Subordinating Wollstonecraft’s philosophy, the selling point of this peculiar ideology has been that whatever an individual woman chooses becomes potentially empowering, if she chooses, and there is no critique of man’s dominion over woman—or how women themselves collaborate in maintaining the political and civil situation of what she calls “the tyranny of man.” To quote Wollstonecraft: “From the tyranny of man, I firmly believe, the greater number of female follies proceed; and the cunning, which I allow makes at present a part of their character, I likewise have repeatedly endeavoured to prove, is produced by oppression” (p. 282). Writers may substitute Goodreads and summaries online for actually reading Wollstonecraft’s book, but the result is a willful distortion.

What material readers “like” the most from Vindication gives an idea of how they read the work—if they do—and what they, for either good or bad, take from it (see image below). The quote “I do not wish them [women] to have power over men; but over themselves” has 1,439 likes; the fifth most liked quote, with 283 likes, says, “It is vain to expect virtue from women until they are, in some degree, independent of men” (p. 221). The most popular line taken from Vindication talks about women having power over themselves rather than power over men, but readers seem noticeably less attracted to Wollstonecraft’s sharp critique of women’s dependency on men.

I have seen arguments pitting Wollstonecraft against feminists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, from Matilda Joslyn Gage to Andrea Dworkin, positing later feminists as deviating from Wollstonecraft’s moral philosophy. The argument goes that, while later feminists have argued that women live as victims of men oppressing them under patriarchy, Wollstonecraft argued for their empowerment as individuals. A post-1970s “victim feminism,” so we hear, took the place of this strange distortion of Wollstonecraft never discussing the oppression of women and never discussing women as victims—because women’s empowerment. In this view, the feminist analysis of men oppressing women becomes man hating, which, apparently, deviates from Wollstonecraft’s 1792 master-slave analogy for man’s relation to woman. This kind of argument very seriously misleads readers about Wollstonecraft’s actual writing to negate modern feminism’s rootedness in her analysis. A question arises: How can women have power over themselves as individuals without seeking any degree of female independence against totalizing dependency on men?

The answer to the lingering “Woman Question” cannot be found in arguing that anything a woman chooses—transgenderism, surrogacy, and prostitution—can be empowering to all women because a woman chooses it. Wollstonecraft’s Vindication tangles with precisely the issue of how individual choice does not happen, as if magically, in a context totally independent of social conditions. But the widespread misrepresentation of Wollstonecraft has stripped the revolutionary consciousness from her moral philosophy, replacing her with a doll. As Dworkin has become a “trans ally” philosopher for the left, Wollstonecraft has become a “tradwife” philosopher for the right—neither doing justice to either woman’s ideas. I argue that a close reading of Wollstonecraft’s Vindication reveals condemnations of “victim feminism” today condemn feminism itself more than feminism gone astray.

Slavery is the analogy Wollstonecraft uses for the oppression of women, described in terms of “a system of oppression,” woman forced into unreasonable dependency on man, that indoctrinates not only women but also men (p. 193). Wollstonecraft’s 1792 master-slave analogy for the sexes predates the “lord-bondsman dialectic” in Hegel’s 1807 Phenomenology of Spirit and, of course, predates Marx and Engels in their development of dialectical materialism by nearly one hundred years.2 This analysis seems the least understood, certainly not “liked,” with her quote about women being “convenient slaves” having only 18 likes contrasting to the one above with 1,439 likes. Here are examples of Wollstonecraft’s rhetoric that demonstrate her feminist analysis of power running counter to liberal distortions of Vindication:

[Women] may be convenient slaves, but slavery will have its constant effect, degrading the master and the abject dependent. (p. 67)

Liberty is the mother of virtue, and if women be, by their very constitution, slaves, and not allowed to breathe the sharp invigorating air of freedom, they must ever languish like exotics, and be reckoned beautiful flaws in nature. (p. 103)

Women, it is true, obtaining power by unjust means, by practising or fostering vice, evidently lose the rank which reason would assign them, and they become either abject slaves or capricious tyrants. (p. 113)

[A]cting the part which they foolishly exacted from their lovers, they become abject woers, and fond slaves. (p. 196)

Women are, in common with men, rendered weak and luxurious by the relaxing pleasures which wealth procures; but added to this they are made slaves to their persons, and must render them alluring that man may lend them his reason to guide their tottering steps aright. (pp. 226)

When, therefore, I call women slaves, I mean in a political and civil sense; for, indirectly they obtain too much power, and are debased by their exertions to obtain illicit sway. (p. 252)

Besides, how can women be just or generous, when they are the slaves of injustice? (p. 277)

Passages throughout Vindication demonstrate Wollstonecraft’s analysis of power and, furthermore, present early formulations of theoretical positions evident in the work of feminist theorists from Gage to Dworkin. Removed from context, however, the line “I do not wish them [women] to have power over men; but over themselves” does no justice to the depth of Wollstonecraft’s analysis. Distortion transforms her into a marionette who supplies a desired line of dialogue fitting today’s no less dreadful convention than what she opposed in her own day.

From 1792 to present, Wollstonecraft’s Vindication continues to be relevant in many ways, from her critique of women’s status as “slaves” and “play-things” to her analysis of war and revolution. She even raises the issue of unconventional women, those like herself, being led to believe themselves to be men due to the political and civil limitations imposed on them on the basis of their sex. “I have been led to imagine,” she writes, “that the few extraordinary women who have rushed in eccentrical directions out of the orbit prescribed to their sex, were male spirits, confined by mistake in female frames” (p. 101). It is not that unconventional women actually have had “male spirits” born in the wrong body, “confined by mistake in female frames,” but that society has subjugated their human development in marking them as “the second sex.” Not recognizing this political reality, a situation evident by now, does nothing for women and girls convinced of the “mistakenness” of their female bodies to be “corrected” into “maleness” by surgical and hormonal interventions.

Wollstonecraft’s Vindication does not put women’s individual choice above understanding women’s social conditions under patriarchy as “the tyranny of man,” an eighteenth-century foremother of the 1970s radical feminist analysis. Today’s antifeminists tell us that feminism must refuse to define woman or else uphold a “gender regime” that oppresses women. Feminism, so we hear, has become an oppressive regime—becoming a “Big Sister,” like the Orwellian Big Brother—because feminists criticize women’s choices for transgenderism, surrogacy, and prostitution. They infantilize women by treating them as if they cannot be criticized while simultaneously complaining about women’s infantilization. To quote Emerson, they “fall into the vulgar mistake” of believing themselves persecuted whenever contradicted—and they hold the monopoly on contradictions. Self-identified “Marxist” critics along these lines should research the following: What have communist regimes done to working-class people who have objected to communism? By contrast, feminism has not rounded up its female dissidents and imprisoned them, executed them and their families, or starved them to death.

Antifeminists have mistaken their perverse fantasies for rigorous critique, and they have alienated themselves from reality itself. They remain mired in superficial ideological wordplay serving grand persecutory delusions. Feminism has perpetrated no Holodomor, also called the Ukrainian famine, or Great Terror, both under Stalin’s Soviet Union; no Great Chinese Famine or Cultural Revolution, like under Mao; no Cambodian genocide, like under Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge.3 The moral indolence of antifeminists makes them fascism’s tools, and they fawn over tyrannical regimes when convenient for their shallow political moralizing. To quote Wollstonecraft: “The indolent puppet of a court first becomes a luxurious monster, or fastidious sensualist, and then makes the contagion which his unnatural state spread, the instrument of tyranny” (p. 83). Perversely, feminism’s modern hecklers confuse the feminist critique of women’s individual choice with prison labor and mass murder beneath truly oppressive totalitarian regimes into modernity. Even more ironically, feminism has become a scapegoat for the left’s many -isms: imperialism, colonialism, capitalism, racism.

Asked why so many women submit to their oppression, as if simply the order of things, Wollstonecraft replies: “Men have submitted to superior strength to enjoy with impunity the pleasure of the moment—women have only done the same” (p. 104). That individual women collaborate in women’s oppression has remained unchanging, as one from any oppressed class, racially or economically, may comply with tyranny against its class. Varieties of retardation not only visible in modern feminism but also evident among its antifeminist counterparts have their roots in the unchecked moral indolence among women that Wollstonecraft criticized in 1792.

If you are unable to become a paid subscriber through Substack, then please feel free to donate via PayPal, if able. I am grateful for reader support!

Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, 1792, excerpts from the Oxford University Press 2008 reissued edition.

They may be convenient slaves, but slavery will have its constant effect, degrading the master and the abject dependent.

To M. Talleyrand-Périgord, Late Bishop of Autun

If the abstract rights of man will bear discussion and explanation, those of woman, by a parity of reasoning, will not shrink from the same test: though a different opinion prevails in this country, built on the very arguments which you use to justify the oppression of woman—prescription.

Consider, I address you as a legislator, whether, when men contend for their freedom, and to be allowed to judge for themselves respecting their own happiness, it be not inconsistent and unjust to subjugate women, even though you firmly believe that you are acting in the manner best calculated to promote their happiness? Who made man the exclusive judge, if woman partake with him the gift of reason?

In this style, argue tyrants of every denomination, from the weak king to the weak father of a family; they are all eager to crush reason; yet always assert that they usurp its throne only to be useful. Do you not act a similar part, when you force all women, by denying them civil and political rights, to remain immured in their families groping in the dark? for surely, Sir, you will not assert, that a duty can be binding which is not founded on reason? If indeed this be their destination, arguments may be drawn from reason: and thus augustly supported, the more understanding women acquire, the more they will be attached to their duty—comprehending it—for unless they comprehend it, unless their morals be fixed on the same immutable principle as those of man, no authority can make them discharge it in a virtuous manner. They may be convenient slaves, but slavery will have its constant effect, degrading the master and the abject dependent.

But, if women are to be excluded, without having a voice, from a participation of the natural rights of mankind, prove first, to ward off the charge of injustice and inconsistency, that they want reason—else this flaw in your NEW CONSTITUTION will ever shew that man must, in some shape, act like a tyrant, and tyranny, in whatever part of society it rears its brazen front, will ever undermine morality.

I have repeatedly asserted, and produced what appeared to me irrefragable arguments drawn from matters of fact, to prove my assertion, that women cannot, by force, be confined to domestic concerns; for they will, however ignorant, intermeddle with more weighty affairs, neglecting private duties only to disturb, by cunning tricks, the orderly plans of reason which rise above their comprehension.

Besides, whilst they are only made to acquire personal accomplishments, men will seek for pleasure in variety, and faithless husbands will make faithless wives; such ignorant beings, indeed, will be very excusable when, not taught to respect public good, nor allowed any civil rights, they attempt to do themselves justice by retaliation.

. . .

But, till men become attentive to the duty of a father, it is vain to expect women to spend that time in their nursery which they, “wise in their generation,” choose to spend at their glass; for this exertion of cunning is only an instinct of nature to enable them to obtain indirectly a little of that power of which they are unjustly denied a share: for, if women are not permitted to enjoy legitimate rights, they will render both men and themselves vicious, to obtain illicit privileges.

[67-68]

Women are, in fact, so much degraded by mistaken notions of female excellence . . .

Introduction

My own sex, I hope, will excuse me, if I treat them like rational creatures, instead of flattering their fascinating graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone. I earnestly wish to point out in what true dignity and human happiness consists—I wish to persuade women to endeavour to acquire strength, both of mind and body, and to convince them that the soft phrases, susceptibility of heart, delicacy of sentiment, and refinement of taste, are almost synonymous with epithets of weakness, and that those beings who are only the objects of pity and that kind of love, which has been termed its sister, will soon become objects of contempt.

. . .

The education of women has, of late, been more attended to than formerly; yet they are still reckoned a frivolous sex, and ridiculed or pitied by the writers who endeavour by satire or instruction to improve them. It is acknowledged that they spend many of the first years of their lives in acquiring a smattering of accomplishments; meanwhile strength of body and mind are sacrificed to libertine notions of beauty, to the desire of establishing themselves,—the only way women can rise in the world,—by marriage. And this desire making mere animals of them, when they marry they act as such children may be expected to act:—they dress; they paint, and nickname God’s creatures.—Surely these weak beings are only fit for a seraglio! Can they be expected to govern a family with judgment, or take care of the poor babes whom they bring into the world?

. . .

Women are, in fact, so much degraded by mistaken notions of female excellence, that I do not mean to add a paradox when I assert, that this artificial weakness produces a propensity to tyrannize, and gives birth to cunning, the natural opponent of strength, which leads them to play off those contemptible infantine airs that undermine esteem even whilst they excite desire. Let men become more chaste and modest, and if women do not grow wiser in the same ratio, it will be clear that they have weaker understandings. It seems scarcely necessary to say, that I now speak of the sex in general. Many individuals have more sense than their male relatives; and, as nothing preponderates where there is a constant struggle for an equilibrium, without it has naturally more gravity, some women govern their husbands without degrading themselves, because intellect will always govern.

[73-75]

[A]s wars, agriculture, commerce, and literature, expand the mind, despots are compelled, to make covert corruption hold fast the power which was formerly snatched by open force.

Chapter I—The Rights and Involved Duties of Mankind Considered

It is of great importance to observe that the character of every man is, in some degree, formed by his profession. A man of sense may only have a cast of countenance that wears off as you trace his individuality, whilst the weak , common man has scarcely ever any character, but what belongs to the body; at least, all his opinions have been so steeped in the vat consecrated by authority, that the faint spirit which the grape of his own vine yields cannot be distinguished.

Society, therefore, as it becomes more enlightened, should be very careful not to establish bodies of men who must necessarily be made foolish or vicious by the very constitution of their profession.

In the infancy of society, when men were just emerging out of barbarism, chiefs and priests, touching the most powerful springs of savage conduct, hope and fear, must have had unbounded sway. An aristocracy, of course, is naturally the first form of government. But, clashing interests soon losing their equipoise, a monarchy and hierarchy break out of the confusion of ambitious struggles, and the foundation of both is secured by feudal tenures. This appears to be the origi n o f monarchica l an d priestl y power , an d th e daw n o f civilization. But such combustible materials cannot long be pent up; and, getting vent in foreign wars and intestine insurrection, the people acquire some power in the tumult, which obliges their rulers to gloss over their oppression with a shew of right. Thus, as wars, agriculture, commerce, and literature, expand the mind, despots are compelled, to make covert corruption hold fast the power which was formerly snatched by open force. And this baneful lurking gangrene is most quickly spread by luxury and superstition, the sure dregs of ambition. The indolent puppet of a court first becomes a luxurious monster, or fastidious sensualist, and then makes the contagion which his unnatural state spread, the instrument of tyranny.

[82-83]

Liberty is the mother of virtue, and if women be, by their very constitution, slaves, and not allowed to breathe the sharp invigorating air of freedom, they must ever languish like exotics, and be reckoned beautiful flaws in nature.

Chapter II—The Prevailing Opinion of a Sexual Character Discussed

To account for, and excuse the tyranny of man, many ingenious arguments have been brought forward to prove, that the two sexes, in the acquirement of virtue, ought to aim at attaining a very different character: or, to speak explicitly, women are not allowed to have sufficient strength of mind to acquire what really deserves the name of virtue. Yet it should seem, allowing them to have souls, that there is but one way appointed by providence to lead mankind to either virtue or happiness.

. . .

Riches and hereditary honours have made cyphers of women to give consequence to the numerical figure; and idleness has produced a mixture of gallantry and despotism into society, which leads the very men who are the slaves of their mistresses, to tyrannize over their sisters, wives, and daughters. This is only keeping them in rank and file, it is true. Strengthen the female mind by enlarging it, and there will be an end to blind obedience; but, as blind obedience is ever sought for by power, tyrants and sensualists are in the right when they endeavour to keep women in the dark, because the former only want slaves, and the latter a play-thing. The sensualist, indeed, has been the most dangerous of tyrants, and women have been duped by their lovers, as princes by their ministers, whilst dreaming that they reigned over them.

. . .

Women ought to endeavour to purify their heart; but can they do so when their uncultivated understandings make them entirely dependent on their senses for employment and amusement, when no noble pursuit sets them above the little vanities of the day, or enables them to curb the wild emotions that agitate a reed over which every passing breeze has power? To gain the affections of a virtuous man, is affectation necessary? Nature has given woman a weaker frame than man; but, to ensure her husband’s affections, must a wife, who, by the exercise of her mind and body, whilst she was discharging the duties of a daughter, wife, and mother, has allowed her constitution to retain its natural strength, and her nerves a healthy tone, is she, I say, to condescend to use art, and feign a sickly delicacy, in order to secure her husband’s affection? Weakness may excite tenderness, and gratify the arrogant pride of man; but the lordly caresses of a protector will not gratify a noble mind that pants for and deserves to be respected. Fondness is a poor substitute for friendship!

. . .

How women are to exist in that state where there is to be neither marrying nor giving in marriage, we are not told. For though moralists have agreed that the tenor of life seems to prove that man is prepared by various circumstances for a future state, they constantly concur in advising woman only to provide for the present. Gentleness, docility, and a spaniel-like affection are, on this ground, consistently recommended as the cardinal virtues of the sex; and, disregarding the arbitrary economy of nature, one writer has declared that it is masculine for a woman to be melancholy. She was created to be the toy of man, his rattle, and it must jingle in his ears whenever, dismissing reason, he chooses to be amused.

. . .

They were made to be loved, and must not aim at respect, lest they should be hunted out of society as masculine.

. . .

What does history disclose but marks of inferiority, and how few women have emancipated themselves from the galling yoke of sovereign man?—So few, that the exceptions remind me of an ingenious conjecture respecting Newton: that he was probably a being of a superior order, accidentally caged in a human body. In the same style I have been led to imagine that the few extraordinary women who have rushed in eccentrical directions out of the orbit prescribed to their sex, were male spirits, confined by mistake in female frames.

. . .

. . . I view, with indignation, the mistaken notions that enslave my sex. . . .

It appears to me necessary to dwell on these obvious truths, because females have been insulated, as it were; and, while they have been stripped of the virtues that should clothe humanity, they have been decked with artificial graces that enable them to exercise a short-lived tyranny. Love, in their bosoms, taking place of every nobler passion, their sole ambition is to be fair, to raise emotion instead of inspiring respect; and this ignoble desire, like the servility in absolute monarchies, destroys all strength of character. Liberty is the mother of virtue, and if women be, by their very constitution, slaves, and not allowed to breathe the sharp invigorating air of freedom, they must ever languish like exotics, and be reckoned beautiful flaws in nature.

As to the argument respecting the subjection in which the sex has ever been held, it retorts on man. The many have always been enthralled by the few; and monsters, who scarcely have shewn any discernment of human excellence, have tyrannized over thousands of their fellow-creatures. Why have men of superior endowments submitted to such degradation? For, is it not universally acknowledged that kings, viewed collectively, have ever been inferior, in abilities and virtue, to the same number of men taken from the common mass of mankind—yet, have they not, and are they not still treated with a degree of reverence that is an insult to reason? China is not the only country where a living man has been made a God. Men have submitted to superior strength to enjoy with impunity the pleasure of the moment—women have only done the same, and therefore till it is proved that the courtier, who servilely resigns the birthright of a man, is not a moral agent, it cannot be demonstrated that woman is essentially inferior to man because she has always been subjugated.

[84, 90, 94-95, 100-101, 103-104]

Women, it is true, obtaining power by unjust means, by practising or fostering vice, evidently lose the rank which reason would assign them, and they become either abject slaves or capricious tyrants.

Chapter III—The Same Subject Continued

Women are every where in this deplorable state; for, in order to preserve their innocence, as ignorance is courteously termed, truth is hidden from them, and they are made to assume an artificial character before their faculties have acquired any strength. Taught from their infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and, roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison. Men have various employments and pursuits which engage their attention, and give a character to the opening mind; but women, confined to one, and having their thoughts constantly directed to the most insignificant part of themselves, seldom extend their views beyond the triumph of the hour. But was their understanding once emancipated from the slavery to which the pride and sensuality of man and their short-sighted desire, like that of dominion in tyrants, of present sway, has subjected them, we should probably read of their weaknesses with surprise.

. . .

Women, it is true, obtaining power by unjust means, by practising or fostering vice, evidently lose the rank which reason would assign them, and they become either abject slaves or capricious tyrants. They lose all simplicity, all dignity of mind, in acquiring power, and act as men are observed to act when they have been exalted by the same means.

It is time to effect a revolution in female manners—time to restore to them their lost dignity—and make them, as a part of the human species, labour by reforming themselves to reform the world.

[112-113]

To rise in the world, and have the liberty of running from pleasure to pleasure, they must marry advantageously, and to this object their time is sacrificed, and their persons often legally prostituted.

Chapter IV—Observations on the State of Degradation to Which Woman Is Reduced by Various Causes

That woman is naturally weak, or degraded by a concurrence of circumstances, is, I think, clear. But this position I shall simply contrast with a conclusion, which I have frequenly heard fall from sensible men in favour of an aristocracy: that the mass of mankind cannot be any thing, or the obsequious slaves, who patiently allow themselves to be penned up, would feel their own consequence, and spurn their chains. Men, they further observe, submit every where to oppression, when they have only to lift up their heads to throw off the yoke; yet, instead of asserting their birthright, they quietly lick the dust, and say, let us eat and drink, for to-morrow we die. Women, I argue from analogy, are degraded by the same propensity to enjoy the present moment; and, at last, despise the freedom which they have not sufficient virtue to struggle to attain. But I must be more explicit.

. . .

Pleasure is the business of woman’s life, according to the present modification of society, and while it continues to be so, little can be expected from such weak beings. Inheriting, in a lineal descent from the first fair defect in nature, the sovereignty of beauty, they have, to maintain their power, resigned the natural rights, which the exercise of reason might have procured them, and chosen rather to be short-lived queens than labour to obtain the sober pleasures that arise from equality. Exalted by their inferiority (this sounds like a contradiction) they constantly demand homage as women, though experience should teach them that the men who pride themselves upon paying this arbitrary insolent respect to the sex, with the most scrupulous exactness, are most inclined to tyrannize over, and despise, the very weakness they cherish.

. . .

In the middle rank of life, to continue the comparison, men, in their youth, are prepared for professions, and marriage is not considered as the grand feature in their lives; whilst women, on the contrary, have no other scheme to sharpen their faculties. It is not business, extensive plans, or any of the excursive flights of ambition, that engross their attention; no, their thoughts are now employed in rearing such noble structures. To rise in the world, and have the liberty of running from pleasure to pleasure, they must marry advantageously, and to this object their time is sacrificed, and their persons often legally prostituted. A man when he enters any profession has his eye steadily fixed on some future advantage (and the mind gains great strength by having all its efforts directed to one point) and, full of his business, pleasure is considered as mere relaxation; whilst women seek for pleasure as the main purpose of existence. In fact, from the education, which they receive from society, the love of pleasure may be said to govern them all; but does this prove that there is a sex in souls? It would be just as rational to declare that the courtiers in France, when a destructive system of despotism had formed their character, were not men, because liberty, virtue, and humanity, were sacrificed to pleasure and vanity.—Fatal passions, which have ever domineered over the whole race!

. . .

Fragile in every sense of the word, they are obliged to look up to man for every comfort. In the most trifling dangers they cling to their support, with parasitical tenacity, piteously demanding succour; and their natural protector extends his arm, or lifts up his voice, to guard the lovely trembler—from what? Perhaps the frown of an old cow, or the jump of a mouse; a rat, would be a serious danger. In the name of reason, and even common sense, what can save such beings from contempt; even though they be soft and fair?

These fears, when not affected, may be very pretty; but they shew a degree of imbecility that degrades a rational creature in a way women are not aware of—for love and esteem are very distinct things.

I am fully persuaded that we should hear of none of these infantile airs, if girls were allowed to take sufficient exercise, and not confined in close rooms till their muscles are relaxed, and their powers of digestion destroyed. To carry the remark still further, if fear in girls, instead of being cherished, perhaps, created, were treated in the same manner as cowardice in boys, we should quickly see women with more dignified aspects. It is true, they could not then with equal propriety be termed the sweet flowers that smile in the walk of man; but they would be more respectable members of society, and discharge the important duties of life by the light of their own reason. “Educate women like men,” says Rousseau, “and the more they resemble our sex the less power will they have over us.” This is the very point I aim at. I do not wish them to have power over men; but over themselves.

In the same strain have I heard men argue against instructing the poor; for many are the forms that aristocracy assumes. “Teach them to read and write,” say they, “and you take them out of the station assigned them by nature.” An eloquent Frenchman has answered them, I will borrow his sentiments. But they know not, when they make man a brute, that they may expect every instant to see him transformed into a ferocious beast. Without knowledge there can be no morality!

Ignorance is a frail base for virtue! Yet, that it is the condition for which woman was organized, has been insisted upon by the writers who have most vehemently argued in favour of the superiority of man; a superiority not in degree, but essence; though, to soften the argument, they have laboured to prove, with chivalrous generosity, that the sexes ought not to be compared; man was made to reason, woman to feel; and that together, flesh and spirit, they make the most perfect whole, by blending happily reason and sensibility into one character.

. . .

Women of quality seldom do any of the manual part of their dress, consequently only their taste is exercised, and they acquire, by thinking less of the finery, when the business of their toilet is over, that ease, which seldom appears in the deportment of women, who dress merely for the sake of dressing. In fact, the observation with respect to the middle rank, the one in which talents thrive best, extends not to women; for those of the superior class, by catching, at least, a smattering of literature, and conversing more with men, on general topics, acquire more knowledge than the women who ape their fashions and faults without sharing their advantages. With respect to virtue; to use the word in a comprehensive sense, I have seen most in low life. Many poor women maintain their children by the sweat of their brow, and keep together families that the vices of the fathers would have scattered abroad; but gentlewomen are too indolent to be actively virtuous, and are softened rather than refined by civilization. Indeed, the good sense which I have met with, among the poor women who have had few advantages of education, and yet have acted heroically, strongly confirmed me in the opinion that trifling employments have rendered woman a trifler. Man, taking her body, the mind is left to rust; so that while physical love enervates man, as being his favourite recreation, he will endeavour to enslave woman:—and, who can tell, how many generations may be necessary to give vigour to the virtue and talents of the freed posterity of abject slaves.

[121, 124, 129-130, 132-133, 148]

Woman in particular, whose virtue is built on mutable prejudices, seldom attains to this greatness of mind; so that, becoming the slave of her own feelings, she is easily subjugated by those of others.

Chapter V—Animadversions on Some of the Writers Who Have Rendered Women Objects of Pity, Bordering on Contempt

Hapless woman! what can be expected from thee when the beings on whom thou art said naturally to depend for reason and support, have all an interest in deceiving thee! This is the root of the evil that has shed a corroding mildew on all thy virtues; and blighting in the bud thy opening faculties, has rendered thee the weak thing thou art! It is this separate interest—this insidious state of warfare, that undermines morality, and divides mankind!

If love have made some women wretched—how many more has the cold unmeaning intercourse of gallantry rendered vain and useless! yet this heartless attention to the sex is reckoned so manly, so polite, that till society is very differently organized, I fear, this vestige of gothic manners will not be done away by a more reasonable and affectionate mode of conduct.

. . .

Woman in particular, whose virtue is built on mutual prejudices, seldom attains to this greatness of mind; so that, becoming the slave of her own feelings, she is easily subjugated by those of others. Thus degraded, her reason, her misty reason! is employed rather to burnish than to snap her chains.

Indignantly have I heard women argue in the same track as men, and adopt the sentiments that brutalize them, with all the pertinacity of ignorance.

. . .

[On Rousseau] For never was there a sensualist who paid more fervent adoration at the shrine of beauty. So devout, indeed, was his respect for the person, that excepting the virtue of chastity, for obvious reasons, he only wished to see it embellished by charms, weaknesses, and errors. He was afraid lest the austerity of reason should disturb the soft playfulness of love. The master wished to have a meretricious slave to fondle, entirely dependent on his reason and bounty; he did not want a companion, whom he should be compelled to esteem, or a friend to whom he could confide the care of his children’s education, should death deprive them of their father, before he had fulfilled the sacred task. He denies woman reason, shuts her out from knowledge, and turns her aside from truth; yet his pardon is granted, because “he admits the passion of love.” It would require some ingenuity to shew why women were to be under such an obligation to him for thus admitting love; when it is clear that he admits it only for the relaxation of men, and to perpetuate the species; but he talked with passion, and that powerful spell worked on the sensibility of a young encomiast. “What signifies it,” pursues this rhapsodist, “to women, that his reason disputes with them the empire, when his heart is devotedly theirs.” It is not empire,—but equality, that they should contend for. Yet, if they only wished to lengthen out their sway, they should not entirely trust to their persons, for though beauty may gain a heart, it cannot keep it, even while the beauty is in full bloom, unless the mind lend, at least, some graces.

. . .

I know that a kind of fashion now prevails of respecting prejudices; and when any one dares to face them, though actuated by humanity and armed by reason, he is superciliously asked whether his ancestors were fools. No, I should reply; opinions, at first, of every description, were all, probably, considered, and therefore were founded on some reason; yet not unfrequently, of course, it was rather a local expedient than a fundamental principle, that would be reasonable at all times. But, moss-covered opinions assume the disproportioned form of prejudices, when they are indolently adopted only because age has given them a venerable aspect, though the reason on which they were built ceases to be a reason, or cannot be traced. Why are we to love prejudices, merely because they are prejudices? A prejudice is a fond obstinate persuasion for which we can give no reason; for the moment a reason can be given for an opinion, it ceases to be a prejudice, though it may be an error in judgment: and are we then advised to cherish opinions only to set reason at defiance? This mode of arguing, if arguing it may be called, reminds me of what is vulgarly termed a woman’s reason. For women sometimes declare that they love, or believe, certain things, because they love, or believe them.

. . .

The senses and the imagination give a form to the character, during childhood and youth; and the understanding, as life advances, gives firmness to the first fair purposes of sensibility—till virtue, arising rather from the clear conviction of reason than the impulse of the heart, morality is made to rest on a rock against which the storms of passion vainly beat.

I hope I shall not be misunderstood when I say, that religion will not have this condensing energy, unless it be founded on reason. If it be merely the refuge of weakness or wild fanaticism, and not a governing principle of conduct, drawn from self-knowledge, and a rational opinion respecting the attributes of God, what can it be expected to produce? The religion which consists in warming the affections, and exalting the imagination, is only the poetical part, and may afford the individual pleasure without rendering it a more moral being. It may be a substitute for worldly pursuits; yet narrow, instead of enlarging the heart: but virtue must be loved as in itself sublime and excellent, and not for the advantages it procures or the evils it averts, if any great degree of excellence be expected. Men will not become moral when they only build airy castles in a future world to compensate for the disappointments which they meet with in this; if they turn their thoughts from relative duties to religious reveries.

Most prospects in life are marred by the shuffling worldly wisdom of men, who, forgetting that they cannot serve God and mammon, endeavour to blend contradictory things.—If you wish to make your son rich, pursue one course—if you are only anxious to make him virtuous, you must take another; but do not imagine that you can bound from one road to the other without losing your way.

[171, 176, 178, 188-189, 190]

[A]cting the part which they foolishly exacted from their lovers, they become abject woers, and fond slaves.

Chapter VI—The Effect Which an Early Association of Ideas Has Upon the Character

Educated in the enervating style recommended by the writers on whom I have been animadverting; and not having a chance, from their subordinate state in society, to recover their lost ground, is it surprising that women every where appear a defect in nature? Is it surprising, when we consider what a determinate effect an early association of ideas has on the character, that they neglect their understandings, and turn all their attention to their persons?

. . .

Every thing that they see or hear serves to fix impressions, call forth emotions, and associate ideas, that give a sexual character to the mind. False notions of beauty and delicacy stop the growth of their limbs and produce a sickly soreness, rather than delicacy of organs; and thus weakened by being employed in unfolding instead of examining the first associations, forced on them by every surrounding object, how can they attain the vigour necessary to enable them to throw off their factitious character?—where find strength to recur to reason and rise superiour to a system of oppression, that blasts the fair promises of spring? This cruel association of ideas, which every thing conspires to twist into all their habits of thinking, or, to speak with more precision, of feeling, receives new force when they begin to act a little for themselves; for they then perceive that it is only through their address to excite emotions in men, that pleasure and power are to be obtained. Besides, all the books professedly written for their instruction, which make the first impression on their minds, all inculcate the same opinions. Educated then in worse than Egyptian bondage, it is unreasonable, as well as cruel, to upbraid them with faults that can scarcely be avoided, unless a degree of native vigour be supposed, that falls to the lot of very few amongst mankind.

. . .

Men, for whom we are told women were made, have too much occupied the thoughts of women; and this association has so entangled love with all their motives of action; and, to harp a little on an old string, having been solely employed either to prepare themselves to excite love, or actually putting their lessons in practice, they cannot live without love. But, when a sense of duty, or fear of shame, obliges them to restrain this pampered desire of pleasing beyond certain lengths, too far for delicacy, it is true, though far from criminality, they obstinately determine to love, I speak of the passion, their husbands to the end of the chapter—and then acting the part which they foolishly exacted from their lovers, they become abject woers, and fond slaves.

[191, 192-193, 196]

As a sex, women are habitually indolent; and every thing tends to make them so.

Chapter VII—Modesty—Comprehensively Considered, and Not as a Sexual Virtue

Men will probably still insist that woman ought to have more modesty than man; but it is not dispassionate reasoners who will most earnestly oppose my opinion. No, they are the men of fancy, the favourites of the sex, who outwardly respect and inwardly despise the weak creatures whom they thus sport with. They cannot submit to resign the highest sensual gratification, nor even to relish the epicurism of virtue—self-denial.

. . .

As a sex, women are habitually indolent; and every thing tends to make them so. I do not forget the spurts of activity which sensibility produces; but as these flights of feelings only increase the evil, they are not to be confounded with the slow, orderly walk of reason. So great in reality is their mental and bodily indolence, that till their body be strengthened and their understanding enlarged by active exertions, there is little reason to expect that modesty will take place of bashfulness. They may find it prudent to assume its semblance; but the fair veil will only be worn on gala days.

. . .

Would ye, O my sisters, really possess modesty, ye must remember that the possession of virtue, of any denomination, is incompatible with ignorance and vanity! ye must acquire that soberness of mind, which the exercise of duties, and the pursuit of knowledge, alone inspire, or ye will still remain in a doubtful dependent situation, and only be loved whilst ye are fair! The downcast eye, the rosy blush, the retiring grace, are all proper in their season; but modesty, being the child of reason, cannot long exist with the sensibility that is not tempered by reflection. Besides, when love, even innocent love, is the whole employ of your lives, your hearts will be too soft to afford modesty that tranquil retreat, where she delights to dwell, in close union with humanity.

[204, 207, 208-209]

The two sexes mutually corrupt and improve each other.

Chapter VIII—Morality Undermined by Sexual Notions of the Importance of a Good Reputation

. . . For I will venture to assert, that all the causes of female weakness, as well as depravity, which I have already enlarged on, branch out of one grand cause—want of chastity in men.

This intemperance, so prevalent, depraves the appetite to such a degree, that a wanton stimulus is necessary to rouse it; but the parental design of nature is forgotten, and the mere person, and that for a moment, alone engrosses the thoughts. So voluptuous, indeed, often grows the lustful prowler, that he refines on female softness. Something more soft than woman is then sought for; till, in Italy and Portugal, men attend the levees of equivocal beings, to sigh for more than female langour.

To satisfy this genus of men, women are made systematically voluptuous, and though they may not all carry their libertinism to the same height, yet this heartless intercourse with the sex, which they allow themselves, depraves both sexes, because the taste of men is vitiated; and women, of all classes, naturally square their behaviour to gratify the taste by which they obtain pleasure and power.

. . .

Contrasting the humanity of the present age with the barbarism of antiquity, great stress has been laid on the savage custom of exposing the children whom their parents could not maintain; whilst the man of sensibility, who thus, perhaps, complains, by his promiscuous amours produces a most destructive barrenness and contagious flagitiousness of manners. Surely nature never intended that women, by satisfying an appetite, should frustrate the very purpose for which it was implanted?

. . .

The two sexes mutually corrupt and improve each other. This I believe to be an indisputable truth, extending it to every virtue. Chastity, modesty, public spirit, and all the noble train of virtues, on which social virtue and happiness is built, should be understood and cultivated by all mankind, or they will be cultivated to little effect. And, instead of furnishing the vicious or idle with a pretext for violating some sacred duty, by terming it a sexual one, it would be wiser to shew that nature has not made any difference, for that the unchaste man doubly defeats the purpose of nature, by rendering women barren, and destroying his own constitution, though he avoids the shame that pursues the crime in the other sex. These are the physical consequences, the moral are still more alarming; for virtue is only a nominal distinction when the duties of citizens, husbands, wives, fathers, mothers, and directors of families, become merely the selfish ties of convenience.

[218-219]

Women are, in common with men, rendered weak and luxurious by the relaxing pleasures which wealth procures; but added to this they are made slaves to their persons, and must render them alluring that man may lend them his reason to guide their tottering steps aright.

Chapter IX—Of the Pernicious Effects Which Arise from the Unnatural Distinctions Established in Society

. . . [L]et me return to the more specious slavery which chains the very soul of woman, keeping her for ever under the bondage of ignorance.

The preposterous distinctions of rank, which render civilization a curse, by dividing the world between voluptuous tyrants, and cunning envious dependents, corrupt, almost equally, every class of people, because respectability is not attached to the discharge of the relative duties of life, but to the station, and when the duties are not fulfilled the affections cannot gain sufficient strength to fortify the virtue of which they are not natural reward. Still there are some loop-holes out of which a man may creep, and dare to think and act for himself; but for a woman it is an herculean task, because she has difficulties peculiar to her sex to overcome, which require almost superhuman powers.

A truly benevolent legislator always endeavours to make it the interest of each individual to be virtuous; and thus private virtue becoming the cement of public happiness, an orderly whole is consolidated by the tendency of all the parts towards a common centre. But, the private or public virtue of woman is very problematical; for Rousseau, and a numerous list of male writers, insist that she should all her life be subjected to a severe restraint, that of propriety. Why subject her to propriety—blind propriety, if she be capable of acting from a nobler spring, if she be an heir of immortality? Is sugar always to be produced by vital blood? Is one half of the human species, like the poor African slaves, to be subject to prejudices that brutalize them, when principles would be a surer guard, only to sweeten the cup of man? Is not this indirectly to deny woman reason? for a gift is a mockery, if it be unfit for use.

Women are, in common with men, rendered weak and luxurious by the relaxing pleasures which wealth procures; but added to this they are made slaves to their persons, and must render them alluring that man may lend them his reason to guide their tottering steps aright. Or should they be ambitious, they must govern their tyrants by sinister tricks, for without rights there cannot be any incumbent duties. The laws respecting woman, which I mean to discuss in a future part, make an absurd unit of a man and his wife; and then, by the easy transition of only considering him as responsible, she is reduced to a mere cypher.

The being who discharges the duties of its station is independent; and, speaking of women at large, their first duty is to themselves as rational creatures, and the next, in point of importance, as citizens, is that, which includes so many, of a mother. The rank in life which dispenses with their fulfilling this duty, necessarily degrades them by making them mere dolls.

. . .

In how many ways do I wish, from the purest benevolence, to impress this truth on my sex; yet I fear that they will not listen to a truth that dear bought experience has brought home to many an agitated bosom, nor willingly resign the privileges of rank and sex for the privileges of humanity, to which those have no claim who do not discharge its duties.

Those writers are particularly useful, in my opinion, who make man feel for man, independent of the station he fills, or the drapery of factitious sentiments. I then would fain convince reasonable men of the importance of some of my remarks, and prevail on them to weigh dispassionately the whole tenor of my observations.—I appeal to their understandings; and, as a fellow-creature claim, in the name of my sex, some interest in their hearts. I entreat them to assist to emancipate their companion, to make her a help meet for them!

Would men but generously snap our chains, and be content with rational fellowship instead of slavish obedience, they would find us more observant daughters, more affectionate sisters, more faithful wives, more reasonable mothers—in a word, better citizens. We should then love them with true affection, because we should learn to respect ourselves; and the peace of mind of a worthy man would not be interrupted by the idle vanity of his wife, nor his babes sent to nestle in a strange bosom, having never found a home in their mother’s.

[225-226, 231]

To be a good mother—a woman must have sense, and that independence of mind which few women possess who are taught to depend entirely on their husbands.

Chapter X—Parental Affection

Woman, however, a slave in every situation to prejudice seldom exerts enlightened maternal affection; for she either neglects her children, or spoils them by improper indulgence. Besides, the affection of some women for their children is, as I have before termed it, frequently very brutish; for it eradicates every spark of humanity. Justice, truth, every thing is sacrificed by these Rebekahs, and for the sake of their own children they violate the most sacred duties, forgetting the common relationship that binds the whole family on earth together. Yet, reason seems to say, that they who suffer one duty, or affection, to swallow up the rest, have not sufficient heart or mind to fulfil that one conscientiously. It then loses the venerable aspect of a duty, and assumes the fantastic form of a whim.

. . .

The formation of the mind must be begun very early, and the temper, in particular, requires the most judicious attention—an attention which women cannot pay who only love their children because they are their children, and seek no further for the foundation of their duty, than in the feelings of the moment. It is this want of reason in their affections which makes women so often run into extremes, and either be the most fond or most careless and unnatural mothers.

To be a good mother—a woman must have sense, and that independence of mind which few women possess who are taught to depend entirely on their husbands.

[233]

[T]aught slavishly to submit to their parents, they are prepared for the slavery of marriage.

Chapter XI—Duty to Parents

A slavish bondage to parents cramps every faculty of the mind; and Mr. Locke very judiciously observes, that “if the mind be curbed and humbled too much in children; if their spirits be abased and broken much by too strict an hand over them; they lose all their vigour and industry.” This strict hand may, in some degree, account for the weakness of women; for girls, from various causes, are more kept down by their parents, in every sense of the word, than boys. The duty expected from them is, like all the duties arbitrarily imposed on women, more from a sense of propriety, more out of respect for decorum, than reason; and thus taught slavishly to submit to their parents, they are prepared for the slavery of marriage. I may be told that a number of women are not slaves in the marriage state. True, but they then become tyrants; for it is not rational freedom, but a lawless kind of power, resembling the authority exercised by the favourites of absolute monarchs, which they obtain by debasing means. I do not, likewise, dream of insinuating that either boys or girls are always slaves, I only insist, that when they are obliged to submit to authority blindly, their faculties are weakened, and their tempers rendered imperious or abject. I also lament that parents, indolently availing themselves of a supposed privilege, damp the first faint glimmering of reason rendering at the same time the duty, which they are so anxious to enforce, an empty name; because they will not let it rest on the only basis on which a duty can rest securely: for, unless it be founded on knowledge, it cannot gain sufficient strength to resist the squalls of passion, or the silent sapping of self-love. But it is not the parents who have given the surest proof of their affection for their children, or, to speak more properly, who by fulfilling their duty, have allowed a natural parental affection to take root in their hearts, the child of exercised sympathy and reason, and not the over-weening offspring of selfish pride, who most vehemently insist on their children submitting to their will, merely because it is their will. On the contrary, the parent, who sets a good example, patiently lets that example work; and it seldom fails to produce its natural effect—filial reverence.

[237-238]

When, therefore, I call women slaves, I mean in a political and civil sense; for, indirectly they obtain too much power, and are debased by their exertions to obtain illicit sway.

Chapter XII—On National Education

Women have been allowed to remain in ignorance, and slavish dependence, many, very many years, and still we hear of nothing but their fondness of pleasure and sway, their preference of rakes and soldiers, their childish attachment to toys, and the vanity that makes them value accomplishments more than virtues.

History brings forward a fearful catalogue of the crimes which their cunning has produced, when the weak slaves have had sufficient address to over-reach their masters. In France, and in how many other countries, have men been the luxurious despots, and women the crafty ministers? Does this prove that ignorance and dependence domesticate them? Is not their folly the by-word of the libertines, who relax in their society; and do not men of sense continually lament that an immoderate fondness for dress and dissipation carries the mother of a family for ever from home? Their hearts have not been debauched by knowledge, or their minds led astray by scientific pursuits; yet, they do not fulfil the peculiar duties which as women they are called upon by nature to fulfil. On the contrary, the state of warfare which subsists between the sexes, makes them employ those wiles, that often frustrate the more open designs of force.

When, therefore, I call women slaves, I mean in a political and civil sense; for, indirectly they obtain too much power, and are debased by their exertions to obtain illicit sway.

[252]

Oppression thus formed many of the features of their character perfectly to coincide with that of the oppressed half of mankind . . .

Chapter XIII—Some Instances of the Folly Which the Ignorance of Women Generates; with Concluding Reflections on the Moral Improvement That a Revolution in Female Manners Might Naturally Be Expected to Produce

Women are supposed to possess more sensibility, and even humanity, than men, and their strong attachments and instantaneous emotions of compassion are given as proofs; but the clinging affection of ignorance has seldom any thing noble in it, and may mostly be resolved into selfishness, as well as the affection of children and brutes. I have known many weak women whose sensibility was entirely engrossed by their husbands; and as for their humanity, it was very faint indeed, or rather it was only a transient emotion of compassion, “Humanity does not consist in a squeamish ear,” says an eminent orator. “It belongs to the mind as well as the nerves.”

But this kind of exclusive affection, though it degrade the individual, should not be brought forward as a proof of the inferiority of the sex, because it is the natural consequence of confined views: for even women of superior sense, having their attention turned to little employments, and private plans, rarely rise to heroism, unless when spurred on by love; and love as an heroic passion, like genius, appears but once in an age. I therefore agree with the moralist who asserts, “that women have seldom so much generosity as men;” and that their narrow affections, to which justice and humanity are often sacrificed, render the sex apparently inferior, especially as they are commonly inspired by men; but I contend, that the heart would expand as the understanding gained strength, if women were not depressed from their cradles.

I know that a little sensibility and great weakness will produce a strong sexual attachment, and that reason must cement friendship; consequently I allow, that more friendship is to be found in the male than the female world, and that men have a higher sense of justice. The exclusive affections of women seem indeed to resemble Cato’s most unjust love for his country. He wished to crush Carthage, not to save Rome, but to promote its vain glory; and in general, it is to similar principles that humanity is sacrificed, for genuine duties support each other.

Besides, how can women be just or generous, when they are the slaves of injustice?

. . .

From the tyranny of man, I firmly believe, the greater number of female follies proceed; and the cunning, which I allow makes at present a part of their character, I likewise have repeatedly endeavoured to prove, is produced by oppression.

Were not dissenters, for instance, a class of people, with strict truth characterized as cunning? And may I not lay some stress on this fact to prove, that when any power but reason curbs the free spirit of man, dissimulation is practised, and the various shifts of art are naturally called forth? Great attention to decorum, which was carried to a degree of scrupulosity, and all that puerile bustle about trifles and consequential solemnity, which Butler’s caricature of a dissenter brings before the imagination, shaped their persons as well as their minds in the mould of prim littleness. I speak collectively, for I know how many ornaments to human nature have been enrolled amongst sectaries; yet, I assert, that the same narrow prejudice for their sect, which women have for their families, prevailed in the dissenting part of the community, however worthy in other respects; and also that the same timid prudence, or headstrong efforts, often disgraced the exertions of both. Oppression thus formed many of the features of their character perfectly to coincide with that of the oppressed half of mankind; for is it not notorious, that dissenters were like women, fond of deliberating together, and asking advice of each other, till by a complication of little contrivances, some little end was brought about? A similar attention to preserve their reputation was conspicuous in the dissenting and female world, and was produced by a similar cause.

Asserting the rights which women in common with men ought to contend for, I have not attempted to extenuate their faults; but to prove them to be the natural consequence of their education and station in society. If so, it is reasonable to suppose that they will change their character, and correct their vices and follies, when they are allowed to be free in a physical, moral, and civil sense.

[277, 282-283]

Under “Further Reading,” I have made selections of various works discussing Wollstonecraft for a survey of modern readings that I have found useful.

Further Reading

Perspectives on Wollstonecraft

Virginia Woolf, “Mary Wollstonecraft,” 1929, in Women and Writing, ed. Michèle Barrett, 1979 (Orlando, FL: Harcourt, Inc., 1980), 96-103.

Eleanor Flexner, Mary Wollstonecraft: A Biography, 1972 (Baltimore, MD: Penguin Books, 1973). See, especially, chapter ten “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792),” 147-166.

Erika Bachiochi, The Rights of Women: Reclaiming a Lost Vision (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2021).

Selected Articles

Moira Ferguson, “Mary Wollstonecraft and the Problematic of Slavery,” Feminist Review 42 (Autumn 1992): 82-102, https://doi.org/10.2307/1395131.

Susan Ferguson, “The Radical Ideas of Mary Wollstonecraft,” Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique 32, no. 3 (September 1999): 427-450, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423900013913.

Laura Brace, “‘Not Empire, but Equality’: Mary Wollstonecraft, the Marriage State, and the Sexual Contract,” The Journal of Political Philosophy 8, no. 4, 433-455, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9760.00111.

Eileen M. Hunt, “The Family as Cave, Platoon, and Prison: The Three Stages of Wollstonecraft’s Philosophy of the Family,” The Review of Politics 64, no. 1 (Winter 2002): 81-119, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0034670500031624.

Eileen Hunt Botting, “Mary Wollstonecraft’s Enlightened Legacy: The ‘Modern Social Imaginary’ of the Egalitarian Family,” The American Behavioral Scientist 49, no. 5 (January 2006): 687-701, https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764205282213.

Virginia Woolf, “Mary Wollstonecraft,” The Nation and Athenæum 46, no. 1 (October 5, 1929), 14; Woolf, “Mary Wollstonecraft,” in Women and Writing, ed. Michèle Barrett, 1979 (Orlando, FL: Harcourt Inc., 1980), 98.

Joseph Dietzgen, who corresponded with Marx, coined “dialectical materialism” in 1887. Earlier in the 1880s, Engels developed a theory of materialist dialectics in his unfinished 1883 work Dialektik der Natur (Dialectics of Nature). Georgi Plekhanov further elaborated the concept of dialectical materialism in his 1891 “Dialectic and Logic,” based on the work of Marx and Engels.

Genocides under communist regimes have been hundreds of thousands to millions in size, each, wiping out swathes of civilian populations around the world, especially in Russia and in China—including working-class people—to impose communism against resistance. Since communist regimes literally have murdered working-class people who have objected to communism, feminism has not been worse merely for criticizing women’s choices. While decrying feminism’s “genocidal hatred” of men, today’s antifeminists talk of feminist influence the way The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Mein Kampf talk of Jewish influence.