Janice G. Raymond on Transsexualism and Transgenderism—Session I

An introduction to Raymond’s work

This post includes the X space audio for the January 28 session about Janice G. Raymond’s work on transsexualism and transgenderism, available on YouTube, and a transcription of it, with additional notes. Thinking about it, I have decided to make all of the sessions public X spaces. It did not make much sense to have spaces labeled every other number and do paid ones for a handful of paid subscribers and then have to do separate recordings on my own, etc.—although, I will make a point of having special offerings for paid subscribers. I have figured out how to take the X space audio, edit it, and put it into YouTube video “podcast” versions available for listeners without X accounts. To make the listening smoother, I have cut the areas around the passages, with the exception of some Q&A parts reproduced with permission. In this recording, I have included my Q&A with Michael Costa, editor-in-chief with Gays Against Groomers (GAG). With the exception of such Q&A content, the video only includes the commentary audio.

Our next session covering Chapter I of The Transsexual Empire and Chapter II of Doublethink will be this coming Wednesday, February 11, at 9:00 PM Central Standard Time (CST).

Sessions

Session I—January 28

TE, “Introduction to the 1994 Edition” (pp. xi-xxxv)

TE, “Introduction. Some Comments on Method (for the Methodical)” (pp. 1-18)

D, “Introduction. From Transsexualism to Transgenderism” (pp. 1-20)

Session II—February 11

TE, “Chapter I. ‘Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Transsexualism’” (pp. 19-42)

D, “Chapter II. The Rapid Rollout of Transgenderism: How Did It Happen?” (pp. 55-86)

Session III—TBA

TE, “Chapter II. Are Transsexuals Born or Made—or Both?” (pp. 43-68)

D, “Chapter I. The New Trans Biologism: Female Brains and Female Penises” (pp. 21-54)

Session IV—TBA

TE, “Chapter III. ‘Mother’s Feminized Phallus’ or Father’s Castrated Femme?” (pp. 69-98)

D, “Chapter III. Self-Declared Men, Transitioning and De-Transitioning” (pp. 87-121)

Session V—TBA

TE, “Chapter IV. Sappho by Surgery: The Transsexually Constructed Lesbian Feminist” (pp. 99-119)

D, “Chapter IV. The Trans Culture of Violence Against Women” (pp. 123-154)

Session VI—TBA

D, “Chapter V. Gender Identity Trumps Sex in Women’s Sports and Children’s Education” (pp. 155-181)

Session VII—TBA

TE, “Chapter V. Therapy as a Way of Life: Medical Values versus Social Change” (pp. 120-153)

TE, “Chapter VI. Toward the Development of an Ethic of Integrity” (pp. 154-177)

Session VIII—TBA

D, “Chapter VI. The Trans Gag Rules: Erasing Women, Pronoun Tyranny, and Censoring Critics” (pp. 183-221)

Session IX—TBA

TE, “Appendix. Suggestions for Change” (pp. 178-185)

D, “Conclusion” (pp. 223-233)

KEYWORDS

Janice G. Raymond, The Transsexual Empire, Doublethink, transsexualism, transgenderism, feminist critique, sex roles, gender, “gender identity,” “sex-conversion surgery,” John Money, Harry Benjamin, Robert Stoller, “gender dysphoria,” medicalization, bodily integrity

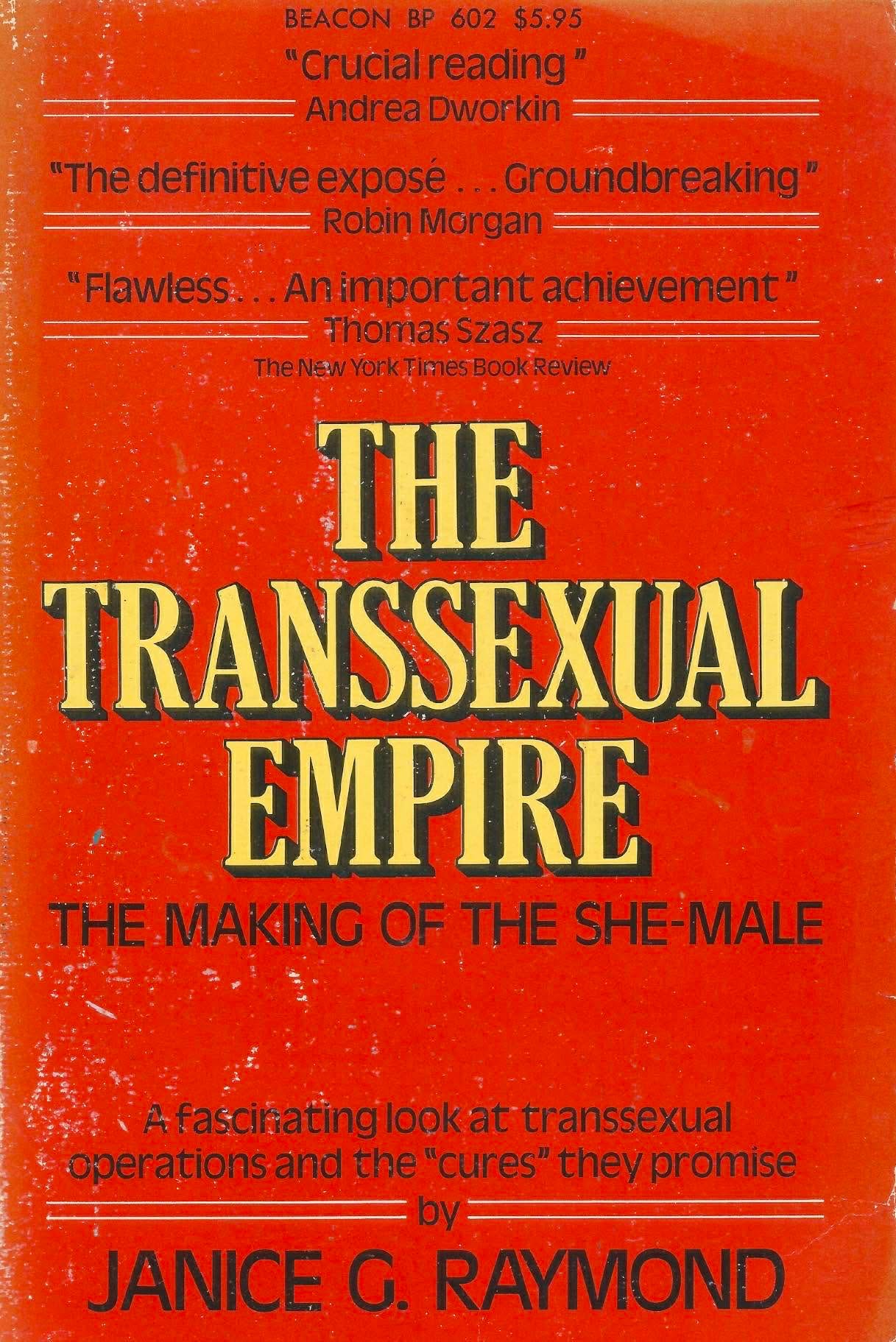

CLECKLEY (Voiceover): Hello. My name is Donovan Cleckley. This YouTube video includes audio from my recent X space, dated Wednesday, January 28, discussing the work of Janice G. Raymond on transsexualism and transgenderism. It is Session I of a small planned series of readings and discussions of Raymond’s 1979 book The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male and her 2021 follow-up titled Doublethink: A Feminist Challenge to Transgenderism. This session provides some background information about Raymond’s Transsexual Empire, such as its earlier developments, and discusses the 1979 original introduction, the 1994 introduction to the Teachers College Press edition, and the 2021 introduction to Doublethink. Thank you all so much for listening.

1979 Introduction to The Transsexual Empire

CLECKLEY: So, to start us off, I want to introduce The Transsexual Empire. It started as a conference paper that Raymond had delivered at the New England Regional American Academy of Religion meeting in 1972. There was a work titled “Beyond Male Morality,” which appeared in 1974 in a collection titled Women and Religion, published by Scholars Press, also for the American Academy of Religion. In that paper, Raymond dealt with the development of certain values in society, particularly talking about the notions of “masculinity” and “femininity,” how they are understood socially, and she talked about the ways in which they are restrictive. By “male morality,” she did not mean that all men were bad; she referred to the values constructed in society, things largely from male-created institutions.

Subsequent to this earlier work was “Transsexualism: The Ultimate Homage to Sex-Role Power” in 1977, which appeared in Chrysalis, an early feminist journal published into the late 1970s, perhaps into the 1980s as well [Note: Chrysalis: A Magazine of Women’s Culture ended in 1980 due to financial difficulties, spanning three years from its first issue in 1977 but producing ten issues, nonetheless]. Although it was discontinued, there were later journals that took up the name Chrysalis—in fact, one being a transgender journal that actually took on the name of a prior feminist publication. Interestingly, when Raymond’s piece appeared in 1977 it was alongside the Black radical feminist Audre Lorde’s “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” which appeared under the title “Poems Are Not Luxuries.” Raymond talks about how that original work that became The Transsexual Empire was her doctoral dissertation that concerned the medical ethics of what, at the time, was known as “sex-conversion surgery.”

We’ll get started with that 1979 introduction. Like I mentioned, we’ll go to some brief discussion just to talk about if you have moments that you found interesting or insightful from the introduction. We can certainly talk about those and just highlight some key moments.

Starting off, one of the one of the interesting things, as it begins, is Raymond talks about how, while transsexualism is defined in psychological and medical terms, as if it is disconnected from social conditions, that as a feminist ethicist, she approached it in terms of how it how it showed what she calls “male-defined values and philosophical/theological beliefs,” which is to say, “beliefs about the so-called natures of women and men” (TE, p. 1). From the very beginning, she brings up John Money, who, as many know, began the first work on “gender identity” with regard to infants. He argued that, for instance, “that the core of one’s gender identity is fixed by the age of eighteen months” (TE, p. 2). Much of the research that Money produced, as Raymond notes, had these beliefs that went unquestioned because he would produce everything in terms of “scientific data.” As we know, over time, Money’s dominion has been questioned, although it has interestingly become integrated into the structure of transgenderism as we know it, with modern trans activists often denying Money’s original role in the creation and the legitimation of transsexualism decades ago.

One of the key terms that Raymond uses in that early introduction in 1979 is “theodicy,” which she says, and this is a great quote:

In this theodicy, as in all religious theodicies, the surrender of selfhood is necessary to a certain extent. In the medical theodicy, transsexuals surrender themselves to the transsexual therapists and technicians. The medical order then tells transsexuals what is healthy and unhealthy (the theological equivalence of good and evil). Thus the classification function of the term transsexualism analyzes a whole system of meaning that is endowed with an extraordinary power of structuring reality. (TE, p. 2)

What she means there, when she talks about theodicy, is in the secular sense. She talks about medicine and psychology as “secular religions,” with regard to transsexualism and the notions of “good” and “evil” become expressed as “healthy” and “unhealthy” that, as we know, later developed into “affirmation”—a way of justifying one’s existence through a therapeutic treatment. Raymond takes issue with what, as she says, is “more and more moral problems have been reclassified as technical problems; and indeed how the very notion of health itself, as generated by this medical model, has made genuine transcendence of the transsexual problem almost impossible” (TE, p. 2).

She starts immediately with acknowledging the difficulties in language surrounding the issue, which was certainly an issue in 1979—now even more so than perhaps then. With the medical literature on transsexualism at the time, there was “masculinity,” “masculine,” “femininity,” “feminine.” And there would often be a failure to draw a distinction that the male who feminized himself was not female, that the medical literature at the time would equate feminization with acquiring “femaleness” and equate masculinization with acquiring “maleness.” It was a kind of buying or taking on sex through this use of the masculine and the feminine, surgically constructed or hormonally constructed, despite it being superficial—which it is—that there was this falseness, a false sense of it being deeper. Raymond says, “To feminize or masculinize into a cultural identity and role is to socialize one into a constructed identity and role” (TE, p. 3). She emphasizes the process of socialization throughout this work. It is not that femininity and masculinity just sit there separate from the society in which people live. Her point in utilizing the language of “masculinization” and “feminization,” as she says, is to point to the superficial stereotyping involved behind this use of surgical and hormonal interventions to give men what they believe to be the semblance of “womanhood” and women what they believe to be the semblance of “manhood.”

She says, “Maleness and femaleness are governed by certain chromosomes, and the subsequent history of being a chromosomal male or female. Masculinity and femininity are social and surgical constructs” (TE, p. 4). She was later criticized over her use of chromosomes in The Transsexual Empire, although the part that her critics leave out is that she talks about the history of being a male or female. So, it’s not just chromosomes, as she was later accused by Judith Shapiro in a criticism which we’ll come back to in the 1994 intro. Shapiro accused her of having a “chromosomes are destiny” view. But Raymond, in fact, discusses how it is not only chromosomes or biology itself, but also the experience of living in a female or male body in society, a fundamental difference between women and men, an embodied difference, not simply chromosomal.

She talks about the origin of the word “transsexualism” and how it was first used by Harry Benjamin in a lecture in 1953 when he was talking at the New York Academy of Medicine. However, it would not appear in the Index Medicus until over a decade later in 1965. Prior to its appearance in the Index Medicus, works dealing with sex-conversion surgery would be classified under “transvestism,” “homosexuality,” or what would be some other category. Transsexualism was not in the Index Medicus. However, she notes that “as transsexualism acquired its own terminological existence and independent classification,” the assumptions of it being a state of being, of it being just there, came into being. She points out the value of using transsexualism, the suffix -ism referring to an ideology. She refers to how it has to do with a system of beliefs, which is to say that it is not just an industry. Industries do not operate independently of ideologies. We recognize the notion of an overarching ideology behind transgenderism, or transsexualism then, seen more recently expressed in Helen Joyce’s Trans: When Ideology Meets Reality from 2021.

CLECKLEY (voiceover): At this point in the audio, when I mentioned Helen Joyce’s 2021 Trans: When Ideology Meets Reality, the space disconnected. I do apologize for the technical difficulties. The session will now continue.

CLECKLEY: The way that “psychiatric syndrome” was used, which Raymond discusses, was interesting. In the late 1960s, work on transsexualism used the phrase “psychiatric syndrome,” and then went on to say, “Is any patient who seeks castration by surgery, by definition psychotic? We do not find this to be the case” (qtd. in TE, p. 6). It is very weird to pretend that the request for castration by surgery, that there’s not any kind of psychosis or anything psychotic about it. It shows that even the use of “psychiatric syndrome” was less an acknowledgement of it as something like a disease, but an attempt to get around the fact that the authors themselves did not think it was even in that.

NOTE: For the quote about seeking castration not being a function of psychosis, refer to Milton T. Edgerton, Norman J. Knorr, and James R. Callison, “The Surgical Treatment of Transsexual Patients,” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 45 (January 1970): 42. This paper represented the peer-reviewed medical literature at the time during the 1970s. I remember talking with a trans-identified man once who insisted that Raymond did not use the up-to-date research for the time, but her references on transsexualism in 1979 consisted of works written in the 1960s and the 1970s.

The earliest work from Money and Green in 1969 indicates they did not believe transsexualism to be of biological origin. There is still no research to indicate that it is of biological origin. Raymond brings up one of the interesting early insights from that period, from the 1960s into the early 1970s: John Money’s concept of “the six sexes.” It sounds ridiculous, but Money defined “chromosomal sex,” “anatomical or morphological sex,” “genital or gonadal sex,” “legal sex,” “endocrine or hormonal sex,” and “psychological sex.” Of course, he split this in this way so that there was an acknowledgement of some kind of varying difference among all of these—and there is a certain amount of subjectivity to the way that Money approached it. Raymond actually notes that with “psychological sex,” it would likely be better to say “psychosocial sex,” indicating that it was not purely psychological, but rather that what he called “psychological sex” did have to do with the socialization of girls and boys in society.

NOTE: From Raymond’s notes, on Money’s concept of “the six sexes,” the reader can refer to John Money, “Sex Reassignment as Related to Hermaphroditism and Transsexualism,” in Richard Green and John Money, eds., Transsexualism and Sex Reassignment (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1969), pp. 91-93.

Apart from referencing Green and Money, who edited Transsexualism and Sex Reassignment in 1969, Raymond brings up the contributions of Robert Stoller, who actually coined “gender identity” in 1964. In his book Sex and Gender, in 1968, Stoller defined the split between sex and gender. He talks about sex in biological terms, and says “the word sexual will have connotations of anatomy and physiology” (Stoller, qtd. in TE, p, 8). However, he says there is “behavior, feelings, thoughts, and fantasies that are related to the sexes but do not have primarily biological connotations” (Stoller, qtd. in TE, p. 8). For the “psychological phenomena,” Stoller basically said, “Okay, well, let’s use gender for all of that.” With Stoller, there was already this split in 1968. For those who have talked about “the true transsexual,” that also already was a thing. In 1969, Ira Pauly, in Green and Money’s 1969 anthology, said, “In the true transsexual there is no question of, or ambivalence about the gender preference, for the identification has been completed for some time at the point when they appear before the physician requesting sex reassignment” (Pauly, qtd. in TE, p. 8). That quote goes back to what Raymond says about theodicy, where medical treatment becomes a way of dealing with the suffering, of dealing with the suffering of women and men who feel this kind of “gender dysphoria,” this “dissatisfaction” that comes into the clinical setting.

NOTE: From Raymond’s notes, the reader can refer to Robert Stoller, Sex and Gender (New York: Science House, 1968), pp. viii, ix; and Ira Pauly, “Adult Manifestations of Female Transsexualism,” in Green and Money, Transsexualism, p. 44. A point worth underscoring here is the extensive psychiatric and medical literature that predated the existence of the 1970s Women’s Liberation Movement. Feminists did not build a medical and legal infrastructure that already existed—and it was not in women’s interests.

Raymond notes that there’s a lot of trouble with the use of the word “gender.” She says that when used with words like “dissatisfaction,” “discomfort,” “dysphoria,” it gives us a sense of everything being able to be reduced to therapy and technical means. It removes the social dimension from the issue. She says:

Feminists have described gender dissatisfaction in very different terms—i.e., as sex-role oppression, sexism, etc. It is significant that there is no specialized or therapeutic vocabulary of black dissatisfaction, black discomfort, or black dysphoria that has been institutionalized in black identity clinics. (TE, p. 9)

I think it is fascinating that Raymond brought up the parallel to transracialism in 1979, noting that there were no clinics that dealt with race the way that there were clinics that dealt with gender. There have been no clinics that deal with race the way they deal with gender, barring the individual exceptions of people like Rachel Dolezal or Martina Big, who have been figures recognized as “transracial.”

NOTE: Rachel Dolezal, also known as Nkechi Amare Diallo, may be the most well-known “transracial” person. See Rachel Dolezal, with Storms Reback, In Full Color: Finding My Place in a Black and White World (Dallas, TX: BenBella Books, Inc., 2017). Dolezal’s case is of interest because she describes extreme distress, to the point of suicidality, over being white only alleviated by “living as Black.” Contrasting Dolezal’s identification, Martina Big is a more extreme case. Once very white and blonde, Big is lesser-known, as she went from recognizably oversized breast implants to blackening her white skin using Melanotan injections, a form of “perma-tanning,”—i.e., medicalized blackface minstrelsy. Big first became known through extreme plastic surgery to reach a bra size of 32S. She underwent twenty-three procedures adding saline to her breast implants. Each breast holds approximately 3,700 cubic centimeters (cc) of saline. She previously started with 32D implants. For a better parallel to “gender identity clinics,” Raymond could have used “racial identity clinics.” As more body modification becomes mainstream, and transgenderism becomes yesterday’s -ism, we may see increasing cases of transracialism.

She notes that “the experts” began to move away from using transsexualism, away from using the -ism, toward the more general use of the word gender dysphoria as of 1975. The Second International Conference on Transsexualism was renamed to the Second International Conference of Gender Dysphoria. The use of “gender dysphoria” became a way to name a condition rather than acknowledge the circumstances of transsexualism that produce “gender dysphoria.” She writes, “To make it the private property, so to speak, of the transsexual empire and its professionals is to superficialize the depths of the questions that lie behind ‘gender dysphoria’ (TE, p. 12). She notes that there have been issues with the way in which the surgery was popularized post-Christine Jorgensen—this is to say into the 1960s. The specific need for surgery was not evident, although some people may have felt that they wanted to “change sex.” She argues that we cannot be certain to what extent the availability of surgery has generated a wider need for it, because the terminology has made it seem as if it was always that way, as if people always needed this surgery and people were just dying without it.

Raymond has been criticized for mostly writing about men because “the transsexual empire” did primarily involve male patients when it began. I will get more into the statistics as we go. Raymond’s argument for it being primarily or almost exclusively a male phenomenon was not just her saying “because patriarchy.” No, it was actually because the statistics indicated that virtually all of the patients were males. On the high end, seen in the study from Harry Benjamin, it was one woman for every eight men. On the low end, it was one woman for every three to four men. On average, there were three to four times as many men seeking transsexual surgeries and/or hormonal interventions. Again, on the high end, it was eight times as many men as women. With a ratio like that, there is a significant imbalance of whose interests would be met.

NOTE: Harry Benjamin’s Transsexual Phenomenon, in 1966, reported eight men for every one woman. Later studies, also referenced in Raymond’s book, reported four and three men to every one woman. The statistics will be discussed in our talk about Chapter I—“‘Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Transsexualism.’”

Going to the end of that first introduction, Raymond talks about how transsexualism is a social problem that cannot be explained without reference to the society in which we live and the sex roles in which women and men come to live. The way that it’s treated in terms of a purely medical phenomenon, as if totally psychological, ends up leaving out the entire dimension of the social context for it. What I would like to emphasize, too—and this is at the very end of her introduction—she talks about how she’s “not arguing that what is natural is good,” “not polarizing technology against nature.” Rather, she’s “making an appeal to the integrity or harmony of the whole” (TE, p. 17). She deals with this in a chapter called “an ethic of integrity.”

She’s not saying that it’s just about a violation of “a static biological nature of maleness or femaleness,” but there is a kind of be-ing and becoming that have to do with bodily integrity and the integrity of our bodies that becomes violated through this this attempt to artificially simulate the opposite sex. Again, she emphasizes that chromosomes contribute to fundamental bodily experience, but chromosomal maleness and femaleness are not the only thing. She says, “I am emphasizing that medicalized intervention produces harmful effects in the transsexual’s body that negate bodily integrity, wholeness and be-ing” (TE, p. 18). She does make a great emphasis on the integrity of the body and bodily integrity that become violated through regimes of surgery and hormones. And she ends the intro:

Transsexualism is a half-truth that highlights the desperate situation of those individuals in our society who have been uniquely body-bound by gender constrictions, but it is not a whole truth. While transsexualism poses the question of so-called gender agony, it fails to give an answer. I hope to show that it amounts to a solution that only reinforces the society and social norms that produced transsexualism to begin with. (TE, p. 18)

And that was that first introduction for The Transsexual Empire in 1979.

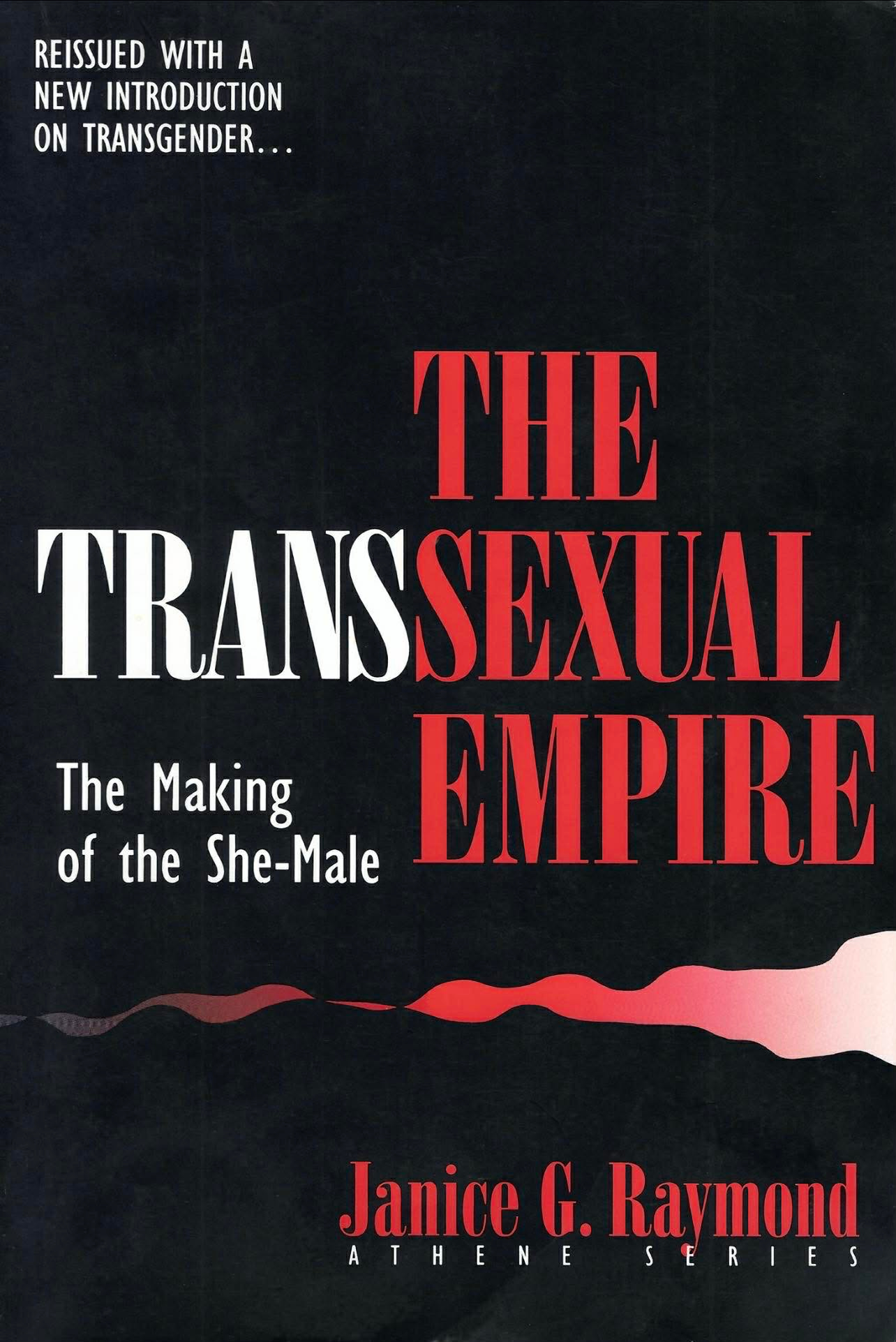

1994 Introduction to The Transsexual Empire

So, the 1994 intro, Raymond comes back with—again, she’s back—and there is humor in it, because there was a strong attempt, which she discusses in the intro to Doublethink, to prevent the second republication of the book. There was already a pushback by 1994 and, of course, this is post-1990 which was the publication of Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet. Already, queer theory had laid its roots, and the environment was far more hostile to publish, even republish, this book. We’ll get into that with Doublethink.

Here she talks about how, in 1979, Johns Hopkins phased out its procedure and dismantled its gender Identity committee. Now this actually did not have to do with The Transsexual Empire, at least Raymond notes that she does not think that was the case. She points to a study from the psychiatrist Jon Meyer, who was director at Johns Hopkins, and he had kept follow-up records of those who had come to the Johns Hopkins clinic. It was noted that it was “a palliative measure [but] it does not cure what is essentially a psychiatric disturbance” (qtd. in TE, p. xi). Meyer then agreed on closing the program.

Trans activists have attributed the closure of the program to Raymond’s Transsexual Empire, but the idea that they read Raymond’s book and took her advice is unlikely. The clinic gave no indication that it did actually sit and read her book and go by her advice; it did have to do with that follow-up study that indicated there was actually not a vast improvement in the mental health of the people who had come to the clinic. Raymond brings up the fact that John Money, who in the 1950s and 1960s, even in the early 1970s, had done his sex/gender or gender identity/sex roles research. He talked about sex roles and gender in more of an abstract way at that time, but his later research, as it got into the 1970s and the 1980s especially, and then into the 1990s, concerned the permissibility of child pornography and incest. Raymond notes that Money, in one of the works that he did into the 1980s, he actually argued, “When the genuine pair-bonding of erotic love has existed between the two partners in incest, then the discovery and disbanding of their partnership, not the partnership itself, may be the source of trauma” (Money qtd. in TE, xii). Money was saying that the worst thing about incest would be the stigma, not the incest itself. He compared a man who commits incest, largely against a girl or young child, to “being a religious deviant in a one-religion society” (Money qtd. in TE, xii). Money effectively viewed incest as being like somebody who does not conform to a dominant religion. Money was originally a large part of the Johns Hopkins program. His gradual writing on the permissibility of “adult-child sex,” which is to say child sexual abuse, became a point of contention. It caused, I think, and Raymond also argues this, that it was likely a strong contributor to the decline of that clinic, certainly more than the likelihood of them actually sitting down and reading The Transsexual Empire.

NOTE: Trans activists do not acknowledge Money’s simultaneous advocacy for transsexualism, “adult-child sex” in purportedly “consensual” pedophilic relations, and child pornography, despite him being an undeniably significant figure in transsexualism’s early institutional support.

Raymond brings up that, by 1994, the number of clinics and centers did not seem to increase or decrease. From 1979 to 1994 it seemed to be about the same [NOTE: Even with the closure of Johns Hopkins or any others, new programs began offering the same services]. The pattern that she observed, which was that most of the patients were men who were desiring to be women, actually held up. She points to the University of Minnesota’s program, which was the second U.S. institution to perform the surgery—85% were men who were transitioning. That was in 1992—85%. It shows that she was utilizing statistics when she said it was largely a male phenomenon. She points to the relative lack of women pursuing social and medical transition having to do with the fact that women’s “gender dissatisfaction” was primarily directed in conformity to femininity, including “breast implants, hormone replacement therapy, infertility hormones and reproductive procedures, and plastic surgery” (TE, p. xiv). Raymond makes a convincing case that it seemed to be less of an “experiment” for women than for men who would play at getting to be “feminine.” She brings up something that came from John Money, which was “it’s easier to construct a hole than a pole,” his method of treating patients who had genital damage, in the tragic case of the Reimer twins, where he had David Reimer subjected to “vaginoplasty,” in the destruction of his male genitalia as an infant.

I think she makes an interesting point on women’s relative accessibility to men versus men’s accessibility to women. She points out that it seems that the idea of maleness is harder for women to access than men to access this sense of being female. She says, “For if maleness were as easily available as femaleness, i.e., if men were as accessible, men, too would be treated like women” (TE, p. xv). There is a distinction between the treatment of women and men.

Raymond brings up the medical model. Thomas Szasz, a prominent critic of psychiatry, provided a book endorsement for The Transsexual Empire. He coined various things, like “transchronological”—a person who wants to be young. Does a poor person who wants to be rich suffer from the disease of being “transeconomical”? Which I think is funny. He even brought up—Does a Black person who wants to be white suffer from the disease of being “transracial”? Raymond highlights these, which is interesting, that Szasz perhaps coined “transracial” in the sense of racial transition. He brought up these—“transchronological,” “transeconomical,” “transracial.” Of course, we do not have corresponding clinics that have to do with age, economic, or race change. We do not think about those in purely medical or psychological terms the way that we think about issues related to “gender.” Raymond brings up the analogy between gender and race highlighting the lack of the presence of clinics that deal with race, age, or economic dissatisfaction, which is fascinating.

Going to the critical responses and critics that dealt with her book, Raymond points to a feminist critic named Annie Woodhouse, who wrote an otherwise good book called Fantastic Women. The problem was she accused Raymond of “essentialism,” which we know is something that is kind of commonly thrown at women who are critical of transsexualism. She argues that Raymond holds this view of the “essence of femininity” defining women. But Raymond actually corrects this and says, “It is the female reality that the surgically-constructed ‘woman’ does not possess, not because women innately carry some essence of femininity, but because these men have not had to live in a female body with all the history that entails” (TE, p. xx). For Raymond, it goes back to the body and bodily integrity. That was one critic of Raymond.

We know that one of her other critics was Sandy Stone, who wrote “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttranssexual Manifesto,” which is the founding document of “transgender studies.” It was written and written in the late 1980s, in 1987 and he continued making changes and editing it, and it appeared in a 1991 collection called Body Guards, which had to do with arguing for “gender ambiguity.” He wrote a kind of critique, which was really just an attack on Raymond. He writes “the transsexual is really text,” and she quotes Stone writing, “In the transsexual as text we may find the potential to map the refigured body onto conventional gender discourse and thereby disrupt it, to take advantage of the dissonances created by such a juxtaposition to fragment and reconstitute the elements of gender in new and unexpected geometries” (Stone, qtd. in TE, xxii). Wow, right? Stone talks about the body-as-text, that it can be taken apart and put back together and made into different things and “unexpected geometries”—like flesh origamies. Stone gives Raymond’s Transsexual Empire a kind of backhanded compliment. He says, of course, it was “the definitive statement on transsexualism by a genetic female academic.” And, then, he follows by saying, “There is some hope to be taken that Judith Shapiro’s work will supersede Raymond’s as such a definitive statement. Shapiro’s accounts seem excellently balanced. . .” (Stone, qtd. in TE, p. xxiii). Raymond notes that Shapiro actually appropriated much of Raymond’s own critique from The Transsexual Empire, but she distances herself from Raymond and presents Raymond as kind of prudish. She says, “Raymond contemplated transsexualism with all the frustration and disgust of a missionary watching prime converts backslide into paganism and witchcraft” (Shapiro, qtd. in TE, p. xxiv). Then, Shapiro brings up all of the anthropological instances of any kind of “gender crossing.” She goes through Native Americans, the xanith in Oman, and woman-to-woman marriages in Africa. She brings all these up as being instances of “transgender,” that rationalize transgenderism. None of those cultural practices, by the way, had a highly well-funded industry, an empire, behind them, so it is a false analogy.

NOTE: Readers may refer to both Shapiro and Stone in Body Guards: The Cultural Politics of Gender Ambiguity, eds. Julia Epstein and Kristina Straub (New York: Routledge, 1991). See Shapiro, “Transsexualism: Reflections on the Persistence of Gender and the Mutability of Sex,” pp. 248-279, and Stone, “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttranssexual Manifesto,” pp. 280-304. Stone’s autoethnographic work has been wrongly considered a “review” when it does not do the essential work of a book review.

Raymond talks about tolerance being misleading, what she calls later in the text “repressive tolerance.” She brings up prominent figures of the 1990s, like RuPaul, where he had said, “You’re born naked and the rest is drag.” And, of course, we know that drag, the mentality of drag, the celebration of it, grew into the 1990s. There were no Drag Queen Story Hours, but, certainly, it was ascending as a kind of celebrated cultural practice. She points out the genuine lack of subversiveness in “cross dressing,” that it reduces the political to a personal style. She brings up the appearance of k.d. lang in a spread for the August 1993 issue of Vanity Fair, where lang is pictured in a very role-defined and sexually objectifying cover photo. In fact, one of the captions says, “I have a little bit of penis envy. They’re ridiculous but they’re cool” (lang, qtd. in TE, p. xxxiii). And then the other caption being: “As much as I hate it, I admire the male sexual drive, because it’s so primal and so animalistic” (lang, qtd. in TE, p. xxxiii). Even “gender nonconformity” was being paired and marketed with a kind of explicit sexual objectification. This notion of “transcending gender” was bound up with sexual objectification. Raymond defines transgenderism this way:

Transgenderism is the product of a historical period that circumscribes any challenge to sex roles and gender definitions to some form of assimilating these roles and definitions. In much of the western world, the general effect of the 1980s has been to move back the feminist gains of the 1960s and 1970s. It has encouraged a style rather than a politics of resistance. (TE, pp. xxxiv)

Individualism takes over as opposed to “collective political challenges to power.” She ends by saying that the ideals of transgenderism look provocative. It seems provocative and subversive, but it does not actually move us beyond gender. It assimilates and reinscribes gender in ways that are harmful, that monetize and institutionalize surgical profiteering off suffering. I like the question that she asks, which refers to Kate Bornstein, a trans activist in the 1980s and the 1990s. He had put out a book called Gender Outlaw. Raymond has a question here that says, “What good is a gender outlaw who is still abiding by the law of gender?” (TE, p. xxxv). I always like that. I think it was such a great turn of phrase there. She says that transgenderism does not present real sexual politics, that a real sexual politics would work toward a transformation moving beyond the reinscribing of gender as such. And that’s the intro to the 1994 edition of Raymond’s Transsexual Empire.

CLECKLEY (Voiceover): With his permission, I have included the commentary from Michael Costa, editor-in-chief with Gays Against Groomers. He joined the space to note the influence of Raymond’s work on subsequent efforts to end the social and medical transitioning of children abused in the process of surgical and hormonal interventions. In 2024, Gays Against Groomers published a book titled The Gender Trap: The Trans Agenda’s War Against Children, work that rightfully acknowledges feminist contributions like Raymond’s. There are some exceptions to the prevailing discourse that scapegoats feminism on the basis of self-declared “feminists” like Donna Haraway [“Cyborg Manifesto,” 1985] and Judith Butler [Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, 1990]. Costa asked some insightful questions, which I have included with my replies, as recorded during the space.

COSTA: Thanks for having me. I appreciate it. I have a question. This is probably my favorite book, so it’s great that you are taking the time to platform it. If people had just listened to lesbians, none of this stuff would be happening right now. I feel like it’s really important for people to know, because the lesbian analysis of this issue is the most comprehensive, in my opinion. I think it’s because lesbians have experienced the negative aspects of gender ideology, from multiple points—from the woman hating to the gay aspect to education and medical malpractice, they know it all.

I write for conservative lesbians, and I’m looking to elaborate on the details of Harry Benjamin and WPATH and the history and the connections there. I’ve reported on the very concerning history of sexological predators like John Money and Harry Benjamin. I want to educate the public and lobby politicians using details about the problematic history and connecting it to the current efforts to dismantle WPATH permanently. I want to use these historical details in my legislative lobbying as a way to provide evidence to the government that this wannabe “medical organization” has always been corrupt and is rooted in backwards views on sex and gender. I also want to incorporate that history into my news reporting, because I’m convinced that gender medicalization is nothing more than a scam, a scam, a scam. It has been since the very beginning, all the way back in the Harry Benjamin days up to the current ROGD [rapid-onset gender dysphoria] scandal we’re currently witnessing unfold in real time. It seems like WPATH has always been riddled with controversy. What about the problematic history of WPATH do you recommend I include in my work?

CLECKLEY: With reference to what Raymond writes in Transsexual Empire, I think it would be worth mentioning the change in name. We know that it changed from HBIGDA, the Harry Benjamin international Gender Dysphoria Association—HBIGDA—to WPATH [World Professional Association for Transgender Health], and the shift was pretty recent. It was named in 1979 in honor of Harry Benjamin, and then rebranded into the 2000s [NOTE: The rebrand from HBIGDA to WPATH was in 2007]. I think that name change is significant in the connection to Harry Benjamin’s original work. Part of the terminology that Raymond uses in The Transsexual Empire, which we no longer really think about, because so much of the language has been taken over by “gender affirmation” and “gender-affirming care,” is that the original terminology was “sex-conversion surgery.” The subtitle for Harry Benjamin’s original Transsexual Phenomenon had “sex conversion” in it. It was his study of “sex conversion” in males and females. It is significant to acknowledge that the language was originally centered around the concept of “conversion,” “conversion surgery,” and that the rebranding of it to “gender affirmation,” the notion of the “gender-affirming care” was specifically to make people think of it not as a “conversion,” not like a negation of the body or a negation of the self, but, instead, this positive “affirmation,” “self-realization.”

I think certainly you could bring up Raymond, of course, and note how she talks about Harry Benjamin when he produced these early definitions. He was, in a way, throwing things at the board to see what stuck. And that’s one of the things that is so egregious about Benjamin’s work. There are inconsistencies when you read The Transsexual Phenomenon. It is strange, the way he talks about “sex conversion,” running the whole gauntlet of it; it is extraordinarily regressive, but it was so effectively rebranded in progressive terms. Like Raymond said, when she defined transgenderism at the end of that 1994 intro, it really did function as a backlash against the developments within the women’s movement from the 1970s into the 1980s. The 1990s marked a significant backlash against the women’s movement.

But, yeah, I would definitely reference Raymond. She brings up the terminology of “sex conversion,” even in the intro, toward the beginning of the book, that I think is significant. I think it is a point that people do not readily bring to mind because the language has changed in ways that has permitted a kind of “reality control,” an Orwellian “reality control,” over how people use language, how they think. I think that would be something to bring up with regard to Raymond’s specific criticisms and her discussion of Harry Benjamin.

COSTA: That was a really great answer. I took notes. Thank you for having these spaces, and I will definitely be a regular listener.

CLECKLEY: Thank you. And was there anything that you wanted to mention that was interesting from the 1994 intro?

COSTA: Raymond discussed basically how it’s different for a man to wear a dress and heels versus a woman wearing pants and comfortable shoes, that nonconformity there is not reciprocal. Being a tom is not the same thing as being a transvestite. Right now we’re seeing these things collide and everything being collapsed under the label of “trans.” So, we have grown men with fetishes, reading books to little girls about why they should become boys, and acting as if this is all the same thing. The reason why the adults, why those men are “trans,” is not the same reason why those kids are “trans.” And I put “trans” in giant quotes. What do you think about what you said about how it’s different for one to be a cross-dressing [male] transvestite versus a woman who likes to wear slacks, and how that is relevant to the current conversation?

CLECKLEY: Raymond does discuss that. I had skipped over it, just because I skipped over some things in the intro, in the interest of time, so we could get to Doublethink. She does make that distinction that women wearing pants is different than men wanting to put on fishnets and wanting to put on skirts, wanting to put on more restrictive clothing that constricts their bodies—clothing that, for the most part, is imposed on women and girls, clothing that does not permit a full range of movement for women and girls. Fishnets and stockings and skirts—these are not regular or average clothes that promote a reasonable range of movement for women and girls; pants are human. You just wear them, and you’re comfortable, and you move around more easily. Raymond notes that women wearing pants gives them the ease of movement that has been historically associated with men.

There is an interesting connection to the first wave of feminism, where women in the nineteenth century talked about dress reform. As we know, the use of bloomers had to do with women wanting to create alternatives to the dresses that they had to wear for so long. The dresses were so restrictive that they caused women literal health issues. These dresses that were corseted obstructed women’s movement and caused actual bodily issues for women. It is fascinating and ironic to have men in the late twentieth century demand access to the restrictive clothing that women seeked for so long to escape, that women had worked so long to escape that restrictive clothing, that clothing that deprived them of full human movement, and, essentially, that infringed on women’s dignity. I think that is a really significant point, and I think that Raymond beautifully illustrates it. In the 1994 intro, this juxtaposes the men who essentially put on skirts, dresses—they do a wonderful “skirt go spinny”-type thing, and they get to be “pretty.” It is restrictive to women. These are clothes or types of clothing that women have worked to escape from, but that in men’s definition of “women,” men’s definition of “womanhood,” that it takes the meaning of woman, that the outfits obscure what women are, and come to define what women actually are, which is part of the horror of the redefinition there.

Thank you so much, Michael, for bringing up that passage; I love that passage from the 1994 intro.

Introduction to Doublethink

If nobody else has anything you want to mention, then we’ll go over the Doublethink intro. As I’ve noted, it will be a little bit quicker because it’s also slightly shorter than the others. But it talks about some important things that I think listeners will find interesting about the publication of Transsexual Empire and subsequent issues that Raymond experienced following the publication of Transsexual Empire.

She talks about, as I noted before, that the original work began as her PhD dissertation, that in the early 1970s she had done work with the women’s health movement, studying ways in which medical practices impacted the lives of women and girls. In fact, one of the areas that Raymond studied was known as “psychosurgery,” formerly called lobotomies, and she looked at the way in which women were actually subjected to psychosurgery at disproportionately higher numbers than men. In Raymond’s view, and in the view of feminists who critiqued psychosurgery, it was a method of social control, of dealing with these women who were seen as “unruly” or who were designated “mentally ill” by men and their families. These women would be taken away and subjected to psychosurgery, lobotomized.

Raymond mentions the continuing attack on her for using the title Transsexual Empire. They say, “Oh, well, that makes you a ‘conspiracy theorist’ because of the word ‘empire.’” But the point of that title, as she explains, was not that it’s all shady and that it is a shadowy cabal. In fact, it is not a shadowy cabal. There was actually—and now certainly is—a gender industry that involves transsexual counseling, surgery, and hormone treatments, and the industry, she says, “deploys a horde of general surgeons, plastic surgeons, endocrinologists, gynecologists, urologists, and psychiatrists” in service of transgenderism (D, p. 2). In that sense, it is an empire—it is an expansive empire. And she points out that, of course, what she wrote about then has since expanded into a kind of “gender identity industrial complex” (D, p. 2).

By the late 1980s—referring to Sandy Stone, although she doesn’t mention him here—trans activists had challenged the original feminist critique. This was actually separate to “the sex wars” of the 1980s. They began to challenge the feminist position, and they inverted it to say the conformity to the sex roles through medicalization actually challenges gender. Instead of what feminists like Raymond said, that medicalization was not a challenge to gender, that it was a challenge to feminism, trans activists inverted it. They totally flipped around the position, and they took roles in the Women’s Studies departments, and those then turned into “Gender Studies.” As we know today, those original Women’s Studies departments are virtually all Gender Studies or some variation of Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies. She says:

As I saw it then and I see it now, transsexualism and transgenderism raise questions of what gender is and how to challenge it, questions that have become more critical to ask and answer in this expanding ethos of transgenderism—an ideology and practice that promotes a ‘gender identity’ different from the sex a person is born with. (D, p. 3)

“In the new wave of transgenderism,” Raymond notes, “gender becomes biology” (D, p. 3). Gender takes on a kind of force of nature for trans activists.

Previously, when we think about the 1960s and the development of transsexualism, the legitimation of it was top-down from John Money, Harry Benjamin, Richard Green, Robert Stoller—these men who defined and talked about the distinction between sex and gender and treatments of it as a “psychiatric disorder.” They didn’t really regard it necessarily as a disorder, except that they medicalized it. But then they didn’t explain that it had any kind of real basis—except it was a desire. We note that there’s actually been a significant shift from 1979 to 2021, where it seems like the professionals are now no longer required to legitimize it, because it has spread across society in such a way that now it is legitimized at every level of society. It became unmoored from where once it was within the clinical domain. Now, it is everywhere. In a way, it escaped the lab, and it is out.

Raymond talks about how Doublethink is much more about girls and women who are transitioning and detransitioning, whereas there were very few females in the 1970s and 1980s who turned to transsexualism and resorted to hormones and surgeries, which is significant. There was a shift where virtually all of the patients treated at the gender clinics were male, overwhelmingly male, and statistics indicated as much. The patient cohort has flipped, and, now, so many of those being “treated” are, in fact, women and girls. There’s still a large segment of men going into the clinics, but there has been a shift, a significant shift that Raymond recognizes.

In Doublethink, she also points out how she wrote a chapter in Transsexual Empire called “Sappho by Surgery,” and mentioned that men who claim to be women would also claim to be “lesbians,” which Sandy Stone did in the women’s community, in the lesbian community, in the 1970s. I wrote in a note on the page, “‘Sappho by Surgery’ has become ‘Sappho by Speech.’” Men no longer have to undergo any kind of surgery or have to do anything; rather, they now can just say they are “lesbians” by speech. Raymond talks about “the biologizing of illusions,” that the trans obsessions, such as men desiring to menstruate, become pregnant, lactate, these female functions they desire in a fetishistic way to be granted to them through medicalization (D, p. 4-5).

Raymond notes the dubious honor of being the first named TERF, i.e., trans-exclusionary radical feminist. We know that “TERF” has expanded to include anyone—particularly women, of course—but anyone who even slightly objects to transgenderism. Raymond was certainly a foremother in this dubious honor, and I say “dubious honor” because of the harassment that it entails. Raymond talks about some of that early censorship that she experienced that she doesn’t discuss in the 1994 intro. She says:

For me, the censorship happened right from the get-go. In the early 1970s as a graduate student, I had applied for a grant to research and write the dissertation that would become The Transsexual Empire. A prestigious U.S. foundation contacted me to say that the grant had been awarded and needed only some proforma administrative signatures. Since one bonus of the grant was paid health insurance, they asked me to make an appointment for a health physical, a standard part of the insurance application process—an exam they paid for and which I promptly underwent. Several weeks later, a colleague who worked at the foundation and who had endorsed my application informed me that the faculty associated with a prominent university gender identity clinic where I had conducted some interviews had complained that my investigation would threaten their work. This was a backhanded compliment and, needless to say, they nixed my grant. (D, pp. 5-6)

They prevented her from receiving a grant on the basis of her early criticism of transsexualism. Then, after the 1994 publication of that reprint of The Transsexual Empire, in 1995 a man had contacted Teachers College Press—that is to say, the publisher—and claimed that the original preface was deliberately omitted from the book, which, by the way, is not really that big of a deal. But the man claimed that it was a case of “scholarly misconduct” and tried to have, basically tried to have the 1994 edition of the book pulled because he argued the book did not print that preface, a couple of pages, that it violated scholarly principles, and, therefore, the book must be pulled from the shelves. The man who accused her of that continued with his attack and tried very hard to have her book pulled. However, the academic dean eventually dropped the charge of “academic fraud” that made no sense. It was a frivolous claim, but the attempt was to have her book pulled.

Around that same period, in the 1990s after she published Women as Wombs: Reproductive Technologies and the Battle over Women’s Freedom, which was a critique of sexual and reproductive technologies in 1993, about their impacts on women, she was at a bookstore. She was doing the launch of Women as Wombs about reproductive technologies. By the way, the book had nothing to do with transsexualism; it did not mention transsexualism or transgenderism. There was not anything extensive about it in that book, but trans activists showed up anyway to the feminist bookstore in New York City, where she did the book launch, and they protested her. She had to walk through a gauntlet of protesters who were threatening, who would follow her to any speaking event. Even if the event had nothing to do with transsexualism or transgenderism, they still came after her.

After she retired from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where she had worked as a Professor of Ethics and a Professor of Women’s Studies, they issued a statement on their website saying:

Given the persistence of legacies of trans-exclusionary radical feminism, including its presence in the history of Women’s Studies in the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, and in response to requests for clarification on this issue from trans communities at UMass and in the Pioneer Valley, we categorically reject transphobia in our department, on our campus, and in our discipline. (qtd. in D, p. 7)

Raymond notes that the “TERF” in question was not named, but it was obvious who the department was referring to, because nobody else was as identified with radical feminism as her, and nobody else had written and done research and writing on transsexualism and transgenderism the way that she did. After her retirement, they issued this, what she calls “this apology for my unspecified presence in the department [that] felt like a heretic’s sentence at her delayed execution” (D, p. 7). They specifically went out of their way to publish a statement saying they regret the way in which “trans-exclusionary radical feminism” had been in their department, which tells you that they do not stand by their professors.

Recapping some of the points that were already made in the 1994 intro, she references Sheila Jeffreys’s Gender Hurts, from 2014, that the word gender was not really used in as much in the 70s, that most often feminists used the term “sex roles,” and that term was used throughout The Transsexual Empire. As I mentioned at the very beginning, that early version of The Transsexual Empire that Raymond wrote in 1977 was titled “Transsexualism: The Ultimate Homage to Sex-Role Power.” Originally, “sex role” was the common terminology used, as opposed to “gender,” and feminists used “sex role” and “sex roles.” Then, of course, it fell into just “gender,” which became a more medical and psychological term, a term that was more abstract and easier to use in the context of something like, say, “gender dysphoria.” Raymond mentions that Jeffreys talks about how “gender” became euphemistic for things like male violence against women, which became “gender-based violence.” Sex became switched with gender, increasingly, and gender became a “stand-in for the term ‘sex,’ as if ‘gender’ itself is biological” (Jeffreys, qtd. in D, p. 9).

She notes some of the dizzying ways that language has multiplied and become so ridiculous as a result of trans tyranny, the force that it has exerted on language. She talks about the branding of women as “transphobic,” that it functions to make people into fearful bystanders incapable of expressing an honest opinion. She says, “Many people want to remain ignorant, not the ignorance of innocence, but a chosen ignorance that wills not to know” (D, p. 10). That’s a line that I really like from Doublethink, from that intro, because it really underscores that the ignorance here is not innocent; it’s that people do not want to know what the reality is. She notes the importance of refusing to capitulate to language on the terms of trans activists—refusing to use, “she/her/hers” for men or “he/him/his” for women, refusing to engage in these reversals, that it matters. It matters to make a conscious objection to it. When it comes to feminist critics of transgenderism, she says, “We champion a Feminism Unmodified, as Catharine MacKinnon has written, although these days, she doesn’t seem to accept that ‘feminism unmodified’ must stand on the shoulders of ‘females unmodified,’ i.e., women who refuse to be defined by men” (D, p. 13). She makes a crack at MacKinnon, who has become, over the years, a prominent trans activist, strangely more in old age—and, of course, she was that decades ago, albeit less known as such. But that is another story.

Raymond says, “Men who identify as women are now capturing a primary place in the history of women” (D, p. 13). She points to the redefinition of women on men’s terms and discusses the perpetrators of violence against men—in this case, “trans women”—that it is most frequently their male domestic partners, most often men who know the other man is male. It is not strangers going out and killing random men in dresses; rather, it is most often the men who are intimate with them, whom they know. She also points out the fact that statistics for violence against women who declare themselves men are virtually nonexistent compared to the amount of statistics for men who declare themselves women. It’s interesting that there are more statistics about men than there are about women, and there’s more concern about the violence the men experience versus the women. She also notes that violence against women within the “trans” and “queer” community—part of what makes it difficult is that, as she points out, it ends up being violence that is perpetrated by other “trans” and “queer” people. It actually ends up being the men within these communities—and there is a tendency not to want to name it, not to want to name that violence.

She references a collection titled You Told Me You Were Different: An Anthology of Harm, edited by Kitty Robinson, which I recommend. This is Robinson, who says, “When someone who has been victimized by a male trans person believes that male trans people are the most stigmatized, oppressed, at risk people on the earth, the act of staying silent about your abuse is positioned as the only morally good option” (Robinson, qtd. in D, p. 16). Women end up being silent because they feel that they should keep these men safe, and that is horrific emotional blackmail that so many of these young women in particular experience. Raymond talks about the value of the voices of women who were formerly “trans,” but who have realized that transition did not solve the underlying problems that they experienced and that they had since then experienced. They came to a kind of “detransition,” which is really embracing their bodies as themselves, returning to a sense of bodily integrity. She talks about the honesty and the value of those narratives, and the goal of Doublethink is to amplify the experiences of those survivors.

NOTE: Even the language of “detransition” can be confusing, but it is a simplified term for working to embrace one’s body in a meaningful way.

Something to end with is how the language is so difficult. She uses an epigraph from George Orwell, from his book 1984, where he writes, “All that was needed was an unending series of victories over your own memory. ‘Reality control,’ they called it: in Newspeak, ‘doublethink’” (Orwell, qtd. in D, p. 1). We see it occur in the difficulty that women have with language. I think the best way to deal with it is to emphasize men and women, but, in some cases, we have to say “trans-identified” to acknowledge someone who claims that status.

NOTE: When trans-identified men perpetrate crimes utilizing their status, such as those Reduxx has documented, insisting the man should be called a man in every headline, not mentioning “trans,” hides the malicious ideology from criticism by refusing to name it.

One of the confusing things about Doublethink is Raymond tries—I’ll make this, at the end, a criticism of the language she tries to use: “self-declared man” and “self-declared woman.” “Self-declared woman” refers to men, and “self-declared man” refers to women. I think she tried to negotiate being able to acknowledge the self-declared-ness of the status of “trans-identified people.” But it does not work out very well in the language. There are moments where the language gets kind of muddled in passages, because it can be confusing. The alternative would have been to say “men who declare themselves women,” “women who declare themselves men”—which is a mouthful each time. It is one of the difficulties with the use of language, with the problems that transsexualism and transgenderism have presented for us in terms of language.

NOTE: It seems worth emphasizing that the struggle for language is because of the ideology and the industry that have disfigured not only human bodies but also thought and language.

She quotes Orwell again on language: “Doublethink means holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously . . . To tell deliberate lies while genuinely believing them . . . to deny the existence of objective reality” (Orwell, qtd. in D, p. 18). She says that there’s a difficulty in the challenge that we “confront a language that has corrupted reality and a gender industry that sustains it” (D, p. 18). She does recap talking about the issues around men declaring themselves “lesbians” and male violence against women. Doublethink focuses more, as she says, on the survivors, emphasizing women surviving transgenderism, surviving the violence to which men subject them, especially within the “trans” and “queer” community. So, that was the intro to Doublethink.

Here at the very end, I’m very thankful that we’ve had listeners who have stayed along for the talk through those intros.

CLECKLEY (Voiceover): Thank you all so much for listening. I will be planning future spaces and recordings to be announced via Substack and social media. I would like to do a few shorter recordings as well, for more brief commentaries that may or may not be spaces themselves. There will be a transcription of this one available on my Substack, linked in the description below. If you found value in this introduction to Janice G. Raymond’s work on transsexualism and transgenderism, then please like, subscribe, and share. It all helps. Again, thank you all so much.

If you are unable to become a paid subscriber through Substack, then please feel free to donate via PayPal, if able. I am grateful for reader support!