This piece comes from my presentation titled “Reading Andrea Dworkin—Symbolic Matricide and Strategic Ignorance as Rhetorical Strategies,” delivered at the Alabama Communication Association (ACA) on July 26, 2025. During the questions, we talked about reasons for the varieties of “benevolent” misrepresentation from those close to Dworkin, including self-preservation late in life and participating in a faddish careerism. I have altered “Reading Andrea Dworkin” (“RAD”) into “Falsifying Andrea Dworkin” (“FAD”) to underscore a problem raised by my presentation and in the questions afterward: marketing by fad.

To think for one’s self, is not even now the tendency of mankind; the few who dare, do so at great peril.

—Matilda Joslyn Gage, Woman, Church, and State1

Introduction—Who Manufactures Knowledge and Why?

Social movement rhetoric is not only texts read in isolation, as if texts can ever be read this way, but also the research surrounding texts and how researchers present the works to readers and what knowledge has been produced and distributed. The women’s movement has been one of the most evident cases where research surrounding women’s texts, the practice of historiography, significantly influences how readers think about women’s rhetoric and, by extension, the women’s movement. Yet a key problem confronting these studies has been the question of “on” versus “for” when undertaking this research and how women’s texts appear.

What factors explain particular exclusions of material that otherwise would give a truer account of the woman as she lived, in all of her specificity—and why include something but exclude otherwise relevant material?

How does research “on” women differ from research “for” women? Writing in 1983, Renate Klein (1983) has raised this question in how research methodology has operated—whether it has accounted for women’s lives or has superimposed values and norms on them. To what extent does research studying a woman take peculiar liberties opposing the will of the woman studied? How does the researcher permit the woman to speak, to what degree, and, further, what contextual information does the researcher include or exclude—and why? What factors explain particular exclusions of material that otherwise would give a truer account of the woman as she lived, in all of her specificity—and why include something but exclude otherwise relevant material? Research for women, Klein (1983) explains, “tries to take women’s needs, interests, and experiences into account and aims at being instrumental in improving women’s lives in one way or another” (p. 90). Feminist methodology maintains an examination of research methods utilized and, even more crucially, emphasizes asking the question why.

Women’s studies, plural, not only in Women’s Studies but also throughout all fields, have uncovered contradictions in manufacturing knowledge. Like Klein, Dale Spender (1981) has noted that Women’s Studies grew from the urgency of women needing to assess/access knowledge about themselves and their lives. The dominant patriarchal paradigm’s notion of “objective” knowledge about women has been very peculiarly manufactured knowledge expressing particular values. Feminists, Spender explains, “have exposed the discrepancies between their meanings and those that have been enshrined as legitimated (objective) knowledge” (p. 172). Exposing these discrepancies, feminist methodology has revealed the politics of knowledge shaping women’s lives and the political nature of education itself. “One of the substantive issues that women’s studies addresses,” Spender (1981) writes, “is that of the construction, organisation and distribution of knowledge” (p. 172). This issue has become even more relevant today in how men have increasingly defined women in the right-wing and left-wing male ideological backlash against the modern women’s movement.

Uncomfortable questions must be asked about the woman being studied, under male eyes, disappearing into the man who studies her and the implications of this queer disappearance of women into men.

Following the feminist critique of manufactured knowledge, this paper approaches reading Andrea Dworkin by considering two rhetorical strategies deployed: symbolic matricide and strategic ignorance. These methods underlie the misrepresentation of Dworkin throughout scholarly writing on her work. Quoted by Julie Bindel (2004), John Berger, known for his 1972 Ways of Seeing, referred to Dworkin as “the most misrepresented writer in the western world.” What Berger says of Dworkin being misrepresented has been as true in her death as in her life, a key difference being that she cannot speak for herself—at least, or so it may seem.

This analysis considers John Stoltenberg’s rewriting of Andrea Dworkin as research “on” rather than “for” women, demonstrating symbolic matricide and strategic ignorance as rhetorical strategies. While Stoltenberg is the executor of Dworkin’s literary estate, his work on Dworkin constitutes a form of research worth critiquing for its methodology as historiography. Among influential scholars, Martin Duberman (2020) has uncritically accepted Stoltenberg’s claims as “legitimated (objective) knowledge” on Dworkin, part of what has influenced other biographical depictions of her. Key problems have included not only discrepancies in Stoltenberg’s accounts, if not falsifications or distortions, but also material being excluded to serve his self-interest to make his arguments “look right.” Why must women’s truth be sacrificed for men’s self-interest? Reading Andrea Dworkin demands truth. To quote Maria Mies (1983): “The postulate of truth itself makes it necessary that those areas of the female existence which so far were repressed and socially ‘invisible’ be brought into the full daylight of scientific analysis” (p. 121). That which has been repressed, material rendered invisible, must become part of how we study women and their works as they have been represented—or, rather, misrepresented. Uncomfortable questions must be asked about the woman being studied, under male eyes, disappearing into the man who studies her and the implications of this queer disappearance of women into men.

Theoretical Framework

Symbolic Matricide

Symbolic matricide has been more typically understood in terms of psychoanalytic theory regarding the separation or alienation of the self from the mother. Under the present conditions of so-called “civilization,” the individual symbolically murders the mother to achieve her or his individuality distinct from the maternal bond. Drawing on Freud and Lacan, Julia Kristeva (1987/2024) writes, “Matricide is our vital necessity, the sine-qua-non condition of our individuation” (p. 21). Far more critical of Freud and Lacan, Luce Irigaray (1986/1994) notes, “The entire male economy demonstrates a forgetting of life, a lack of recognition of debt to the mother, of maternal ancestry, of the women who do the work of producing and maintaining life” (p. 7). The mother represents the material, the mat(t)er, from which all life comes, so it seems paradoxical that she must be denied her sovereign existence (Brodribb, 1992).

The persuasiveness of symbolic matricide lies in how the man denies the woman’s creative (re)productive capacity and “births”—which is to say plasticizes—the woman in his image.

Nevertheless, individuation has relied on maternal denialism, that women birth people and ideas, all made from their flesh, not recognized as female labor—the ideological basis for women’s exploitation and oppression in man-made civilization. Despite the mother’s labor as the material basis of all labor, intellectual labor included, matricide occurs in a social and political context of male identity dependent on female negation, that of man dispossessing woman. Women birth all people and their ideas, but women become subordinated to men’s ideas about women—regardless of any malignant or “benevolent” intentions (Dworkin, 1983; Mies 1986/2014). The persuasiveness of symbolic matricide lies in how the man denies the woman’s creative (re)productive capacity and “births”—which is to say plasticizes—the woman in his image. This rhetorical strategy provides a partial explanation for how women’s lives become transmogrified in service to men’s desires.

Strategic Ignorance

Strategic ignorance comes into play when an individual faces a potential conflict between what she or he feels or desires to be true versus truth, a discrepancy that may otherwise trigger distress and the need to reconsider one’s position. Kaitlin Woolley and Jane L. Risen (2018) have noted that information avoidance functions to protect some intuitive preference. Considered another way, individuals may avoid being informed on the concrete/the material to defend the abstract/the immaterial. Where sensing preference focuses on concrete details and provable facts, intuitive preference privileges “what could be” over “what is.” Feelings and desires trump facts.

The deployment of strategic ignorance, therefore, preserves one’s feeling of “rightness,” the desire to “look right,” against the reality of truly being wrong.

This psychological defense mechanism defends against whatever may undermine or destabilize one’s altered “reality” exposed as fantasy born of self-interest. Examples include anything from not wanting to know the calories of one’s food to not wanting to know the policies of one’s president. The deployment of strategic ignorance, therefore, preserves one’s feeling of “rightness,” the desire to “look right,” against the reality of truly being wrong. This rhetorical strategy has permitted men to assert—or reassert—dominion over women through “misreadings” that “overlook” discrepancies, effectively persuading the audience through legitimating ignorance as “knowledge.”

Saving the Sentence—Seeing Editorial Surgery

I know you are simply trying to keep her work relevant. I am curious, though, to know your thoughts: Would you agree that, with this piece, you have taken liberties with her writing that she did not want?

—Nikki Craft to John Stoltenberg, February 2, 20162

A Simple Question of Integrity

As seen above, the exchange between Craft and Stoltenberg had to do with a piece titled “Are You Listening, Hillary? President Rape Is Who He Is,” posted to the Andrea Dworkin website, posthumously in 2007, which Stoltenberg wanted replaced with a new version in 2016. Beyond including an extended introduction and postscript, Stoltenberg made significant alterations to the piece, even moving sentences around in the text. By 2016, Dworkin had been dead for just over ten years, so, obviously, it was not her moving around sentences and changing her original text from what she had written. After Craft challenged his editorializing of Dworkin, Stoltenberg admitted she was “completely correct,” but the incident exposed him “forgetting” his commitment “to maintain the integrity of her written work” (Craft, 2016). Even more interestingly, Stoltenberg did not provide the unedited version of the text upon Craft’s request, which prevented her, or anybody else, from seeing to what extent he altered Dworkin’s writing. This incident demonstrates strategic ignorance and symbolic matricide as rhetorical strategies persuading readers to accept Dworkin in Stoltenberg’s image. Strategic ignorance seems evident in Stoltenberg’s “forgetting”; Dworkin was very emphatic about her writing not being subjected to editorializing akin to what has been done. Corresponding with this strategic ignorance, symbolic matricide emerges in the posthumous negation of the text she birthed in favor of Stoltenberg imposing a second “birth” upon it.3

Case Study—Stoltenberg, “Andrea Dworkin Was a Trans Ally,” 2020

This conflict over Stoltenberg’s edits made to “Are You Listening, Hillary? President Rape Is Who He Is” in 2016 was not the end of what Craft (2016) refers to as his “editorial surgery on Dworkin’s sexual politics.” Since 2014, Stoltenberg has portrayed Dworkin as uncritically supporting transsexualism, through the 1970s and 1980s, and modern transgenderism, 1990s onward, under the banner of her being a so-called “trans ally.” Stoltenberg’s earliest version of this argument appeared in a 2014 piece at Feminist Times, followed by a 2020 piece titled “Andrea Dworkin Was a Trans Ally.” For his evidence, Stoltenberg cites (1) the last chapter of Woman Hating (1974), (2) “The Root Cause” (1975), and (3) “Biological Superiority: The World’s Most Dangerous and Deadly Idea” (1977). All of the works that Stoltenberg cites as his evidence of Dworkin being a so-called “trans ally” came into publication from 1974 to 1977.4 Of the three, however, only the last chapter of Woman Hating discusses transsexualism. More than Stoltenberg, Martin Duberman has uncritically accepted Stoltenberg’s version of Dworkin, as seen in the 2020 biography Andrea Dworkin: The Feminist as Revolutionary. Since these claims have impacted the perception of Dworkin, it seems worth examining (1) what the textual evidence says, including discrepancies, and (2) whose interests this portrayal benefits.

Considering Dworkin’s regret over the last chapter in Woman Hating, it seems questionable, at best, to reference it the way Stoltenberg and Duberman do as Dworkin’s authoritative view.

Interviewed by Cindy Jenefsky in 1989, Dworkin “noted that even though feminists and pornographers were moving in different directions at the time Woman Hating was written, they still shared common roots in the counterculture and the sexual liberation movement” (Jenefsky, 1998/2018, p. 139). After 1974, the Dworkin of the seventies, early Dworkin, continued to diverge from the sexual values she internalized from the counterculture and “sexual liberation” influential on left-wing activists of the 1960s-1970s. These cultural influences explain how pornography continued to be embraced into the 1980s-1990s—despite critics like Dworkin who identified the industry’s harms to women and girls. While the last chapter of Woman Hating did not support pornography, it did uncritically advance rhetoric heavily influenced by “sexual liberation” ideology. Hence, during the same interview with Jenefsky, Dworkin reflected on it: “I think there are a lot of things really wrong with the last chapter in Woman Hating” (Jenefsky, 1998/2018, p. 139). For reference, the last chapter of Woman Hating, referred to by Dworkin in her statement, begins on page 174 and ends on page 193. The section titled “Transsexuality” starts at the bottom of page 185 and ends at the top of page 187. When Nikki Craft designed the Andrea Dworkin Online Library (ADOL) in 1995, collaborating with Dworkin very closely, there were passages Dworkin approved from her books reprinted there—including material from Woman Hating. Craft has discussed it as a day-by-day process, done with very great care, where Dworkin was emphatic about which texts should appear. Working on the ADOL website, years following Dworkin’s 1989 reflection, the only material she approved from Woman Hating was from the beginning, page 53 through page 63: her early critique of pornography. Considering Dworkin’s regret over the last chapter in Woman Hating, it seems questionable, at best, to reference it the way Stoltenberg and Duberman do as Dworkin’s authoritative view.

Both Stoltenberg and Duberman exclude Dworkin’s statement on there being “a lot of things really wrong with the last chapter in Woman Hating.” Though Duberman includes Jenefsky’s book listed among sympathetic readings of Mercy, Dworkin’s 1990 novel, he does not engage with Dworkin’s changed perspective years later over the last chapter of Woman Hating. Like Stoltenberg, he neglects considering the problems with citing this 1974 text as representative of Dworkin’s views in a writing career that spanned from the early 1970s until her death on April 9, 2005. Had Duberman provided this strategically ignored evidence to the reader, as detailed here, it would have undermined his and Stoltenberg’s work on Andrea Dworkin. Unsurprisingly, this example of Dworkin explicitly noting her self-reproach over the last chapter of Woman Hating is not the only conveniently missing context.

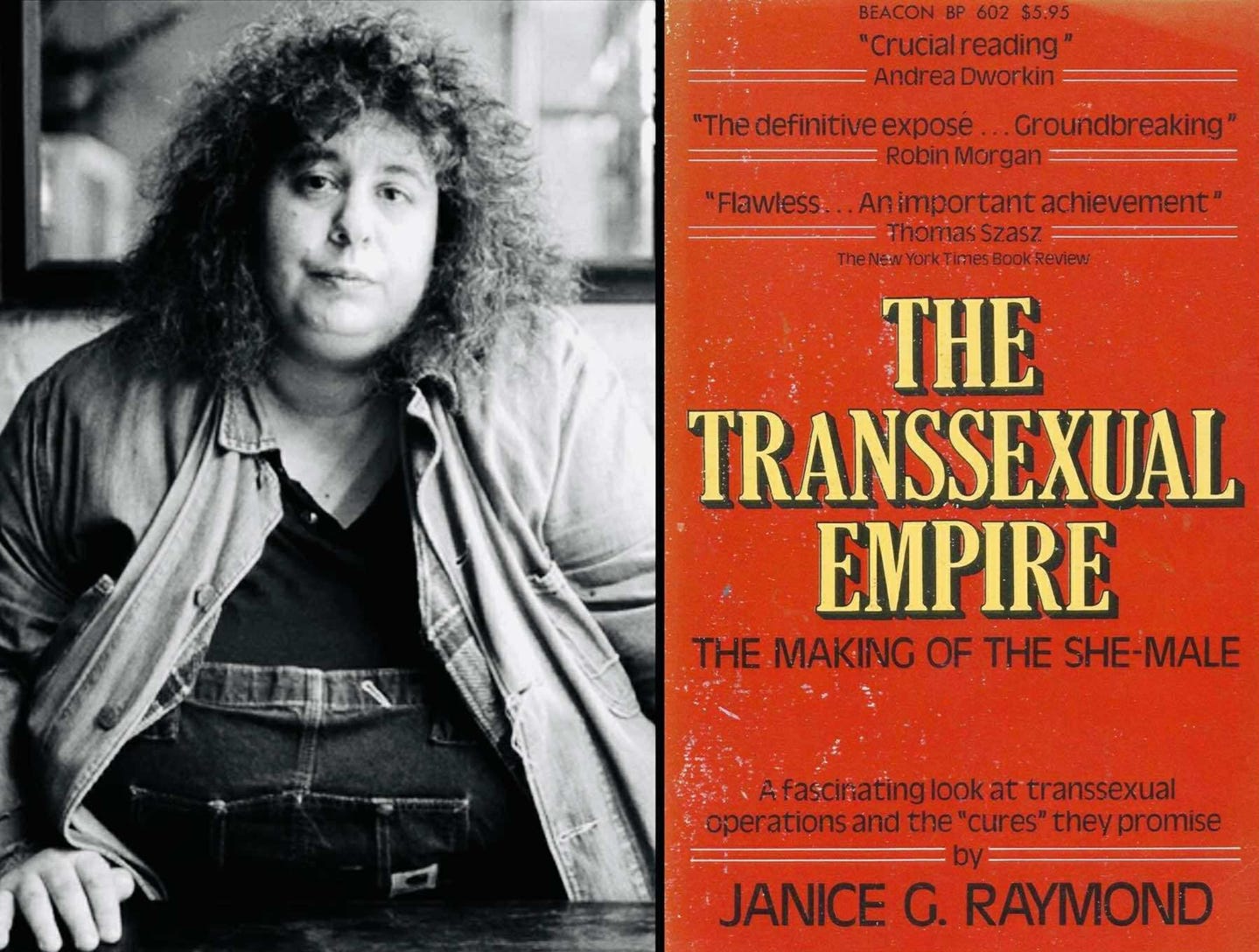

With Stoltenberg and Catharine A. MacKinnon as his references, Duberman makes false claims about Dworkin’s friendship with lesbian radical feminist Janice G. Raymond, who authored The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male in 1979. “For a time in the seventies,” Duberman (2020) writes, Dworkin was “somewhat friendly with Janice Raymond, whose transphobic 1979 book The Transsexual Empire deplored the ‘medicalization’ of gender that encouraged surgical intervention to create ‘a woman according to man’s image’” (p. 161.). The evidence that all of them, including MacKinnon, exclude is that Dworkin and Raymond discussed Woman Hating, particularly the section on transsexualism. In 1977, Raymond wrote a piece titled “Transsexualism: The Ultimate Homage to Sex-Role Power” that appeared in the third issue of Chrysalis. Raymond’s piece was an earlier version of The Transsexual Empire in progress before its publication in 1979. Raymond (1977) writes:

Andrea Dworkin, in her otherwise insightful book Woman Hating, stated that until sex roles disappear (and thus also transsexualism), sex-change operations should be provided ‘by the community as one of its functions. This is an emergency measure for an emergency condition.’ . . . With Dworkin, I would affirm that transsexualism is the result of the stereotyped sex roles of a rigidly gender-defined society. But is transsexualism really the ‘emergency answer to an emergency situation,’ or does it prolong the emergency? And is it the basic duty of ‘the community’ (presumably the feminist community) to provide such treatment? (pp. 11-12)

Despite its total omission from accounts on Dworkin’s views, this passage has tremendous significance: Raymond critiqued Dworkin by name, and, from Raymond’s account, Dworkin responded privately to her accepting rather than rejecting her critique. In her Doublethink: A Feminist Challenge to Transgenderism, Raymond (2021) notes that “Dworkin only objected to my words ‘otherwise insightful’” (p. 46). Dworkin had exactly the humility others lack, and, three years after Woman Hating’s publication, we have this evidence of her rethinking her own less critical thinking about transsexualism.

For Dworkin, transsexualism was transitory, not to be prolonged indefinitely, another part of her 1974 perspective that Stoltenberg, MacKinnon, and Duberman have strategically ignored.

Even in Woman Hating, Dworkin (1974) explains that “community built on androgynous identity will mean the end of transsexuality as we know it […] [A]s roles disappear, the phenomenon of transsexuality will disappear” (p. 186-187). For Dworkin, transsexualism was transitory, not to be prolonged indefinitely, another part of her 1974 perspective that Stoltenberg, MacKinnon, and Duberman have strategically ignored. “These words,” Raymond (2021) argues, “present a challenge to how Stoltenberg has channeled her views” (p. 46). Against the evidence, Stoltenberg has continued insisting that Dworkin’s view expressed in Woman Hating makes her a so-called “trans ally,” a dubious claim even with reading only the 1974 text. The more details taken into account, however, the more difficult it becomes to fit Dworkin’s perspective into the dominant “gender-affirming care” paradigm known today. Dworkin envisioned life beyond gender polarity by abolitionism through social change as opposed to assimilationism through individual medicalization. Describing transsexualism in terms of “an emergency measure for an emergency condition” does not even remotely imply Dworkin viewing it as something to be perpetuated (Dworkin, 1974, p.186). Nevertheless, Dworkin understood individual distress over sex-role stereotyping and the way in which meaning given to one’s sex disfigures one’s humanity.

Dworkin’s sense of identification with others’ suffering was not irreconcilable with critiquing how transsexualism insufficiently responds to gender polarity through medicalizing it.

In his Andrea Dworkin, Duberman (2020) argues that Raymond’s critique of transsexualism “was a view that Andrea deplored, and she let Raymond know it at some length” (p. 161). As his evidence, Duberman cites a letter Dworkin wrote to Raymond, dated January 15, 1978, about so-called “transsexuals,” in which she clarified her perception of “their suffering as authentic” (Dworkin, 1978, as cited in Duberman, 2020, p. 161). From what Duberman quotes from her letter to Raymond, Dworkin expressed compassion for males “in rebellion against the phallus” and females “seeking a freedom only possible to males in patriarchy” (Dworkin, 1978, as cited in Duberman, 2020, p. 161). Based on the quoted material, however, the letter does not support Duberman’s claim that Dworkin deplored Raymond’s view and told her off. Instead, her 1978 letter seems more like Dworkin was explaining her view to Raymond following Raymond’s 1977 critique of Woman Hating.5 Dworkin remained compassionate toward others’ suffering, an empathy ironically prevalent among feminists, including Raymond, condemned as “TERFs”: “trans-exclusionary radical feminists.” Dworkin’s sense of identification with others’ suffering was not irreconcilable with critiquing how transsexualism insufficiently responds to gender polarity through medicalizing it.

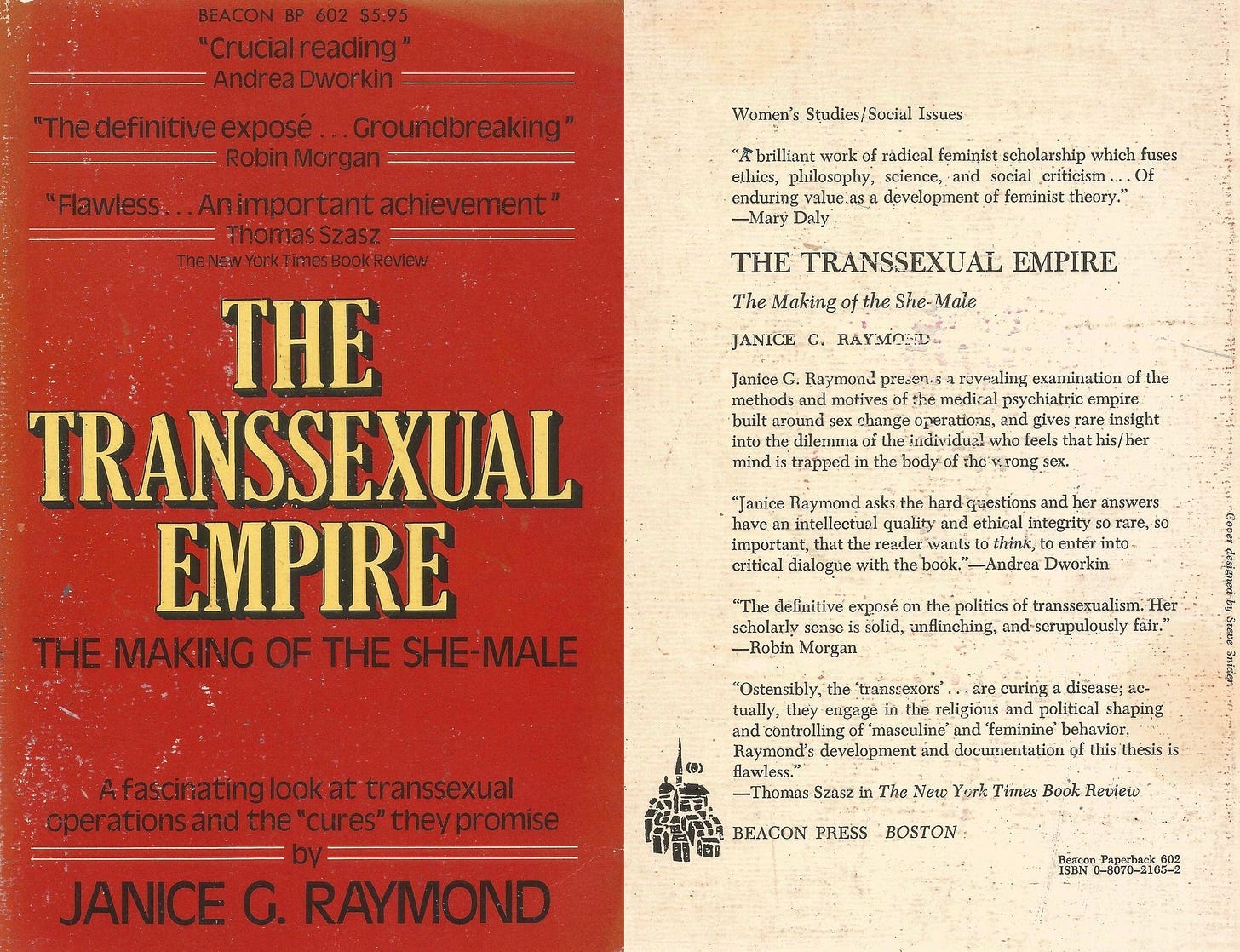

Among suspicious cases of “forgetting,” Stoltenberg, MacKinnon, and Duberman have minimized Dworkin’s professional and personal connection with Raymond and have strategically ignored evidence suggesting otherwise. In other words, they have made an obvious but ultimately ineffective effort to negate the friendship between Dworkin and Raymond. “For a time in the seventies,” Duberman (2020) writes, Dworkin was “somewhat friendly with Janice Raymond” (p. 161). Duberman’s framing is that Dworkin and Raymond were “somewhat friendly” during the 1970s and, upon publication of The Transsexual Empire in 1979, Dworkin cut ties with Raymond in protest of her being “transphobic,” holding a view Dworkin “deplored.” Duberman’s use of that 1978 letter implies an end to Dworkin and Raymond being “somewhat friendly.” But this is not what actually happened. After Raymond critiqued Dworkin in 1977 and after Dworkin’s 1978 letter to Raymond clarifying her view, Dworkin wrote a book endorsement for Raymond’s Transsexual Empire in 1979. While Duberman includes Dworkin’s 1978 letter to Raymond, framed very dubiously, he excludes Dworkin endorsing Raymond’s book published one year later. Endorsing Raymond’s Transsexual Empire, Dworkin writes:

Janice Raymond asks the hard questions and her answers have an intellectual quality and ethical integrity so rare, so important, that the reader wants to think, to enter into critical dialogue with the book.

Beyond Dworkin’s endorsement of Raymond’s Transsexual Empire, their collaborative relationship included Dworkin being acknowledged in relation to “Sappho by Surgery: The Transsexually Constructed Lesbian-Feminist,” in The Transsexual Empire (see Raymond, 1979/1994, p. viii). Two years later, Dworkin (1981) acknowledged Raymond in Pornography: Men Possessing Women among “people [who] helped me substantially,” listed alongside friends like Kathleen Barry, Gena Corea, and H. Patricia Hynes, Raymond’s long-term friend and collaborator (p. 225). Raymond’s Transsexual Empire also appeared in Dworkin’s bibliography for Pornography, though not specifically discussed in the body of the work (see Dworkin, 1981/1989, p. 268). Dworkin’s 1981 critique of men colonizing lesbians through pornography corresponds with Raymond’s 1979 critique of heterosexual males as “lesbian feminists” in “Sappho by Surgery.”

Contrary to what Duberman claims, available published evidence, as provided here, indicates a lifelong friendship between Dworkin and Raymond that extended to ongoing collaboration in their work.

In fact, Dworkin’s friendship with Raymond extended far longer than Duberman implies. Just a few years later, again contrasting Duberman’s characterization of their relationship as only “somewhat friendly” during the 1970s, Dworkin appears in the acknowledgments for Raymond’s 1986 book A Passion for Friends: Toward a Philosophy of Female Affection. “The courage, work, and friendship of Andrea Dworkin, Robin Morgan, and Kathy Barry have been a source of inspiration and strength to me,” Raymond (1986/2001) writes. “They remind me that radical feminism lives and thrives and that female friendship is indeed personal and political” (p. ix). Unsurprisingly, then, Raymond’s A Passion for Friends appears one year later in the bibliography for Dworkin’s 1987 book Intercourse, with Raymond’s work not critiqued as “transphobic” but referenced as informing Dworkin’s analysis (see Dworkin, 1987/2007, p. 293). Into the 1990s, Raymond’s 1993 book Women as Wombs: Reproductive Technologies and the Battle over Women’s Freedom includes Dworkin among “[o]ther friends [who] have helped in a variety of ways” (p. xiv). Finally, Raymond appears referenced positively by Dworkin in her 2000 book Scapegoat: The Jews, Israel, and Women’s Liberation related to Raymond’s work with the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women (CATW), with the proofs for Raymond’s Women as Wombs also cited in Dworkin’s bibliography (see Dworkin, 2000, p. 329, p. 407.). Contrary to what Duberman claims, available published evidence, as provided here, indicates a lifelong friendship between Dworkin and Raymond that extended to ongoing collaboration in their work. Obviously, Dworkin and Raymond were not just “somewhat friendly” during the 1970s.

Very interestingly, in a reply to TransAdvocate founder and editor-in-chief Cristan Williams, dated May 1, 2014, from the archived version of Stoltenberg’s original Feminist Times piece, he (2014) quotes Dworkin’s blurb saying “Crucial reading” but excludes the full text of her book endorsement. To Williams’s question, which Stoltenberg weirdly prompted Williams to ask, Stoltenberg provides a convoluted explanation, asserting that Dworkin “never retracted” her view put forth in Woman Hating.6 His attempt at explaining himself includes the interesting claim that he and Dworkin agreed with Raymond’s Transsexual Empire on surgical and hormonal interventions—except, now, this medicalization, more widespread than in 1979, no longer reinforces gender polarity. Stoltenberg (2014) adds:

We did not foresee that upon publication the book would become anathema to trans people—for some of whom those selfsame surgical/hormonal inventions would be beneficial and necessary.

However, in the very same paragraph, Stoltenberg explains (2014) “the historical fact remains that the men who pioneered medicalizing gender disphoria [sic] had some very problematic, one might say sadistically male-supremacist, attitudes and agendas.” To what extent has the medical landscape truly changed that he can argue what was “very problematic, one might say sadistically male-supremacist” has become “feminist”? Referencing the men who pioneered, Stoltenberg appears to be referring to male sexologists like Harry Benjamin (1885-1986) and John Money (1921-2006), a collaborator with the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association (HBIGDA), founded in 1979.7 HBIGDA rebranded to the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) in 2007, a name change that did not undo the attitudes and agendas Stoltenberg found problematic decades ago. Stoltenberg (2014) explains that “it was Raymond’s exposure of the values pervading this medicalizing that Andrea and I both thought was important for people to know and understand.” How can Dworkin have “deplored” Raymond’s view in The Transsexual Empire, as Duberman claims, since 2014 Stoltenberg’s account contradicts 2020 Stoltenberg’s one?

To date, Williams has not questioned Stoltenberg’s otherwise questionable explanation and, instead, has uncritically propagated this “editorial surgery on Dworkin’s sexual politics.” When confronted with the evidence, actually called by Stoltenberg to explain things to me, Williams (2021a) claimed, “Even sandy stone reviewed TS Empire [The Transsexual Empire]. A mere review =/= a repudiation of her trans friends, her commentary on JR [Janice Raymond], or her trans-inclusive legal work” (emphasis added).8 The problem is that Dworkin’s endorsement for Raymond’s Transsexual Empire was not a review, and Sandy Stone’s essay was, clearly, not an endorsement—also not even a review. Nor is there any “commentary on JR” where Dworkin actually disagrees with Raymond, other than the 1978 letter, as discussed above, dated before Dworkin endorsed The Transsexual Empire in 1979. And the “trans-inclusive legal work” Williams attributes to Dworkin was the inclusion of “transsexuals” in the Dworkin-MacKinnon Anti-Pornography Civil Rights Ordinance among those who could use the civil rights framework if harmed through pornographic exploitation. Raymond never objected to so-called “transsexuals” being able to utilize the Dworkin-MacKinnon civil rights framework. Williams calling it “trans-inclusive” seems misleading when it describes “[t]he use of men, children, or transsexuals in the place of women,” as specified in the Ordinance (MacKinnon & Dworkin, 1997, p. 429). All-inclusive, the Ordinance totally separates the category “transsexuals” from women and men, which ironically can be read as dehumanizing, and does not validate men as women and women as men. Criticized for gaslighting, Williams (2021b) replied to me:

I think perhaps you’re the one doing the gaslighting. Either Olivia [Olivia Records] and Sandy Stone reviewed TE [The Transsexual Empire], and sent their replies to JR [Janice Raymond] as Dworkin did or she didn’t. Which is it? Either Dworkin wrote that she didn’t agree with JR’s overall take on trans people or she didn’t. Which is it?

But the discussion had nothing to do with Sandy Stone and Olivia Records, both very explicitly opposing Raymond’s lesbian feminist critique of Stone as a heterosexual male, a self-identified “lesbian feminist,” colonizing lesbian feminism. As extensively noted, Dworkin and Raymond corresponded about Woman Hating during the late 1970s—and Dworkin agreed with Raymond after the 1978 letter Duberman references, further indicated by her endorsement of Raymond’s Transsexual Empire in 1979. I stopped replying to Williams, since I had already quoted Dworkin’s endorsement in full—and the difference between an endorsement and a review should be more than self-evident to Williams, a published scholar. Relying wholly on Stoltenberg, MacKinnon, and Duberman, Williams has published works like “Radical Inclusion: Recounting the Trans Inclusive History of Radical Feminism” (2016) and, very ironically titled, “The Ontological Woman: A History of Deauthentication, Dehumanization, and Violence” (2020). Williams has been one of the leading “activist-scholars” in the “academic” field of transgender studies, seen in Transgender Studies Quarterly (TSQ), who has contributed significantly to “knowledge” of “trans history.” Misrepresentation breeds misrepresentation.

Conclusion—Whose Story Is It Anyway?

It is easy to say it another way. I will refuse.

—Gertrude Stein, “Saving the Sentence,” How to Write9

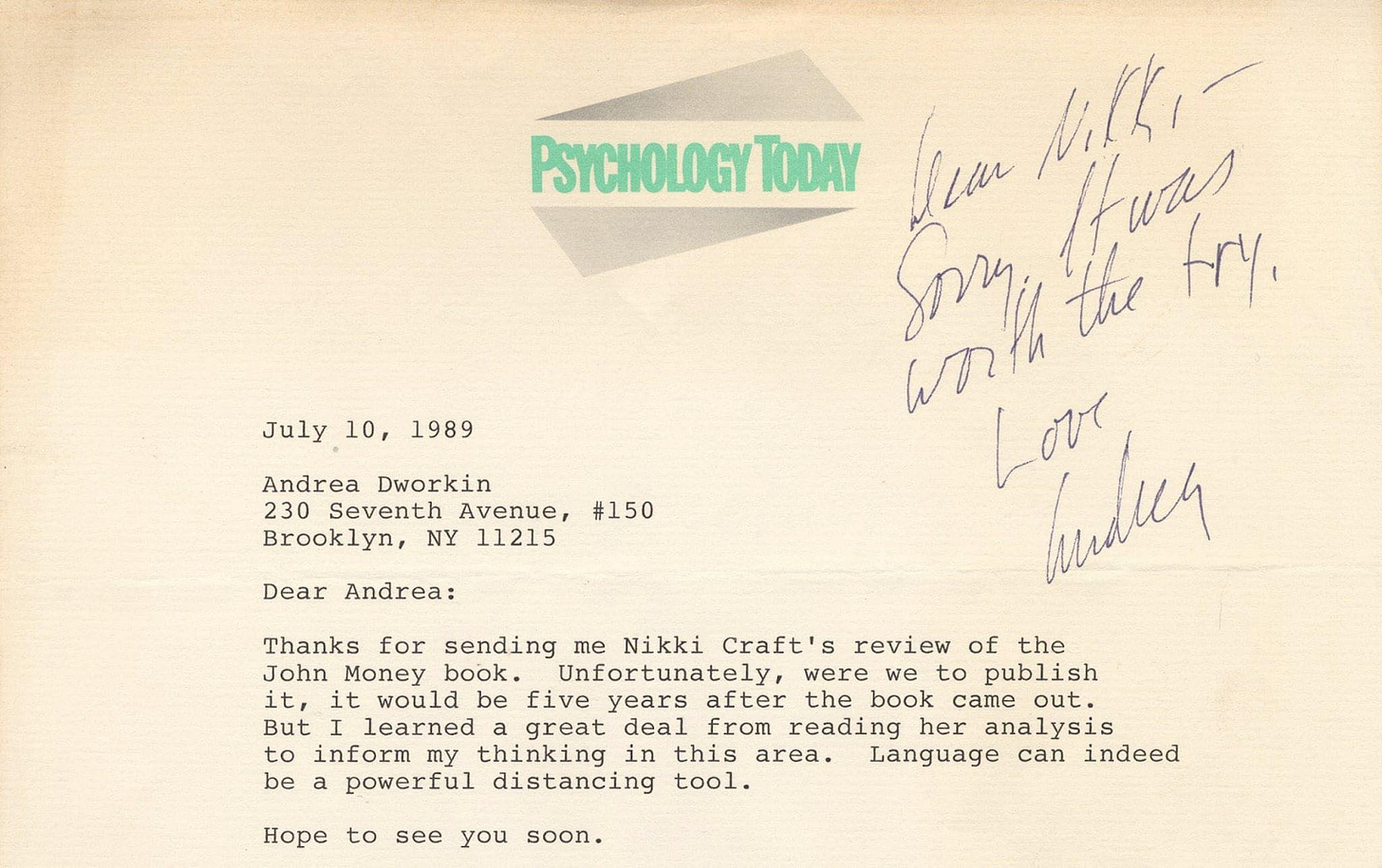

Andrea Dworkin should be treated with respect, which necessitates truth. “Pornography tells lies about women,” Stoltenberg (1981/2000) writes. “But pornography tells the truth about men” (p. 106). Pornography is not all that tells lies about women and truths about men. How male historians do their research on women can tell lies about women. Returning to Mies’s vital point, women’s historiography must search for “areas of the female existence which so far were repressed and socially ‘invisible’” (Mies, 1983, p. 121). For instance, Nikki Craft and I have talked about Dworkin’s work giving helpful comments on a paper of Craft’s during the late 1980s into the late 1990s critical of John Money and his promotion of “sex change.” Dworkin felt the paper deserved publication so much so that she sent it to Psychology Today. On July 10, 1989, the editor wrote the following to Dworkin:

Thanks for sending me Nikki Craft’s review of the John Money book [The Destroying Angel: Fitness and Food in the Legacy of Degeneracy Theory, Graham Crackers, Kellogg's Corn Flakes and American Health History (1985)]. Unfortunately, were we to publish it, it would be five years after the book came out. But I learned a great deal from reading her analysis to inform my thinking in this area. Language can indeed be a powerful distancing tool.

Sending the rejection letter to Craft, Dworkin wrote, circa July 1989: “Dear Nikki,— Sorry. It was worth the try. Love, Andrea.”

Given the discrepancies, it would be worth readers being able to have knowledge about what Dworkin and Raymond actually said in those letters, how these women’s ideas really developed—and not merely what men have made of them.

Looking at how these men have written on Dworkin, all done with the collaboration of MacKinnon, it really seems worth asking: Whose story is it anyway? Within a Burkean rhetorical framework, strategic ignorance and symbolic matricide share elements of the dialectic of the scapegoat. There is a “chosen vessel,” ritualistic alienation, and “the unification of those whose purified identity is defined in dialectical opposition to the sacrificial offering” (Burke, 1962/1969, p. 406). There is “a rebirth of the self,” as Burke (1962/1969), terms it, as the real Dworkin must be negated to advance others’ interests, as they present their falsification of her image as her (p. 407). Research for women requires applying feminist methodology to give as close an idea of the real woman as one possibly can without doctoring her into nonbeing.

To no surprise, Stoltenberg, MacKinnon, Duberman, and Williams, among many others, have not discouraged this investigation of the politics of knowledge—and what it means not only for Dworkin but also for other women. It would be comforting to think the various omissions and distortions have been a series of “accidents” that just so happen to support a peculiarly institutionalized narrative. However, this analysis has indicated more of a conspiracy to hide otherwise significant details, strategically ignoring them or symbolically murdering them, to make an otherwise false narrative true. From Duberman to Williams, biographical accounts on Dworkin have been falsified through excluding inconvenient evidence. An ethical approach would involve (1) acknowledging Dworkin’s change of view from 1974 to 1979 and (2) releasing the unedited correspondence between Dworkin and Raymond about The Transsexual Empire. Given the discrepancies, it would be worth readers being able to have knowledge about what Dworkin and Raymond actually said in those letters, how these women’s ideas really developed—and not merely what men have made of them. If a man truly seeks “gender justice,” then why persistently lie about a woman to make her in his image?

If you are unable to become a paid subscriber through Substack, then please feel free to donate via PayPal, if able. I am grateful for reader support!

References

Bindel, J. (2004, Sept. 30). A life without compromise. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2004/sep/30/gender.world

Brodribb, S. (1992). Nothing mat(t)ers: A feminist critique of postmodernism. Spinifex Press.

Burke, K. (1962/1969). A grammar of motives. University of California Press.

Craft, N. (2016, March 7). Altering Andrea: How John Stoltenberg performs editorial surgery on Dworkin’s sexual politics. The Papers of Nikki Craft.

Daly, M. (1973/1985). Beyond god the father: Toward a philosophy of women’s liberation. Beacon Press.

Duberman, M. (2020). Andrea Dworkin: The feminist as revolutionary. The New Press.

Dworkin, A. (1974). Woman hating: A radical look at sexuality. Plume.

Dworkin, A. (1981/1989). Pornography: Men possessing women. Plume.

Dworkin, A. (1983). Right-wing women: The politics of domesticated females. Perigee Books.

Dworkin, A. (1987/2007). Intercourse. Basic Books.

Dworkin, A. (2000). Scapegoat: The Jews, Israel, and women’s liberation. The Free Press.

Irigaray, L. (1986/1994). A chance to live. Thinking the difference: For a peaceful revolution (pp. 3-35). Routledge.

Jenefsky, C., with Russo, A. (1998/2018). Without apology: Andrea Dworkin’s art and politics. Routledge.

Klein, R. (1983). How to do what we want to do: Thoughts about feminist methodology. In Bowles, G., & Klein, R.D. (Eds.), Theories of women’s studies (pp. 88-104). Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Kristeva, J. (1987/2024). Black sun: Depression and melancholia (Leon S. Roudiez, Trans.). Columbia University Press.

MacKinnon, C.A., & Dworkin, A. (1997) (Eds.). In harm’s way: The pornography civil rights hearings. Harvard University Press.

Mies, M. (1983). Towards a methodology for feminist research. In Bowles, G., & Klein, R.D. (Eds.), Theories of women’s studies (pp. 117-139). Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Mies, M. (1986/2014). Patriarchy and accumulation on a world scale: Women in the international division of labor. Spinifex Press.

Raymond, J.G. (1977). Transsexualism: The ultimate homage to sex-role power. Chrysalis, 3, 11-23.

Raymond, J.G. (1979/1994). The transsexual empire: The making of the she-male. Teachers College Press.

Raymond, J.G. (1986/2001). A passion for friends: Toward a philosophy of female affection. Spinifex Press.

Raymond, J.G. (1993/2019). Women as wombs: Reproductive technologies and the battle over women’s freedom. Spinifex Press.

Raymond, J.G. (2021). Doublethink: A feminist challenge to transgenderism. Spinifex Press.

Spender, D. (1981). Education: The patriarchal paradigm and the response to feminism. In Spender, D. (Ed.), Men’s studies modified: The impact of feminism on the academic disciplines (pp. 155-173). Pergamon Press.

Stoltenberg, J. (1989/2000). The forbidden language of sex. Refusing to be a man: Essays on sex and justice (pp. 102-106). UCL Press.

Stoltenberg, J. (2014, April 28). Andrea was not transphobic. Feminist Times. https://web.archive.org/web/20180801010005/http:/archive.feministtimes.com/%E2%80%AA%E2%80%8Egenderweek-andrea-was-not-transphobic

Stoltenberg, J. (2020, April 8). Andrea Dworkin was a trans ally. Boston Review. https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/john-stoltenberg-andrew-dworkin-was-trans-ally

Williams, C. (2016, May). Radical inclusion: Recounting the trans inclusive history of radical feminism. Transgender Studies Quarterly (TSQ), 3(1-2), 254-258. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-3334463

Williams, C. (2020, July). The ontological woman: A history of deauthentication, dehumanization, and violence. The Sociological Review, 68(4), 718-734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120938292

Williams, C. (2021a, March 25, 1:57 PM). Twitter/X. https://x.com/cristanwilliams/status/1375159876012421125

Williams, C. (2021b, March 25, 10:59 PM). Twitter/X. https://x.com/cristanwilliams/status/1375296411940630529

Woolley, K., & Risen, J. L. (2018). Closing your eyes to follow your heart: Avoiding information to protect a strong intuitive preference. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(2), 230-245. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000100

Matilda Joslyn Gage, Woman, Church, and State, 1893 (Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2002), 501.

Craft’s letter to Stoltenberg, dated February 2, 2016, appears in her “Altering Andrea: How John Stoltenberg Performs Editorial Surgery on Dworkin’s Sexual Politics” (March 7, 2016), seen in The Papers of Nikki Craft.

There are pages of evidence, including material from Craft’s email, indicating significant alterations Stoltenberg has made, which, going almost ten years later, he has not yet released in the unedited form to give readers an opportunity to see the original text as Dworkin wrote it.

For the sake of space, this analysis will deal with how Dworkin’s views shifted by 1979 rather than analyzing the 1974, 1975, and 1977 texts piece by piece as being insufficient to make a sweeping claim about her on the basis of three texts from the 1970s.

Neither Stoltenberg nor Duberman has provided the unedited correspondence between Dworkin and Raymond, which prevents the reader from understanding to what extent Stoltenberg and Duberman have misrepresented the exchange between Dworkin and Raymond.

Commenting to Stoltenberg, on April 30, 2014, Williams had written, “You asked that I come to the comment section and ask the following question,” and then asks a question for Stoltenberg to provide a prepared answer to the question he sent to Williams.

Apart from Benjamin, the founder, founding members were Paul A. Walker, Richard Green, Jack C. Berger, Donald R. Laub, Charles L. Reynolds Jr., Leo Wollman, and Jude Patton, all born male—except for Patton, “self-identified” as “male.”

Sandy Stone is the author of “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttranssexual Manifesto,” a 1987 essay that was neither a review nor an endorsement for Raymond’s Transsexual Empire.

Gertrude Stein, How to Write, 1931 (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 2018), 11.